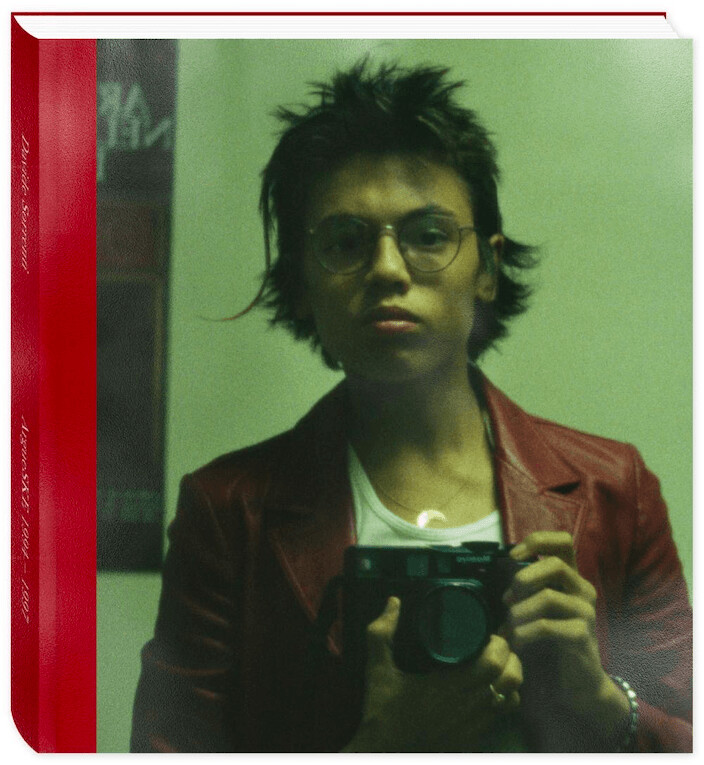

Davide Sorrenti excelled at the part of photography that takes place long before a camera comes into play. He got people to relax, to be vulnerable and unselfconscious. (To be naked, too, sometimes.) Small and young and rapscallionish, he slid into complicated situations with ease, arrogance, and poise. He was the sort of photographer people in front of the lens wanted to please, because in his big-ego, small-package cocksureness, he seemed privy to some idea of beauty or freedom that maybe, if you let him snap the picture, you might access too.

In ArgueSKE 1994–1997 (IDEA, $95), the first full-scale gathering of Sorrenti’s work, the photos are both offhand and striking, indifferently lit, sometimes eerie and sometimes absent. Mainly, he photographed his intimates—skaters, models, downtown layabouts, and so on—lavishing upon them the romance of his lens without ever asking them to rise to its keen eye. Jammed in the back of a car, his friends look sleepy and suspicious. The actress Milla Jovovich—who dated Sorrenti’s older brother Mario—lies prone on the edge of a rooftop, flirting with gravity. Sorrenti’s girlfriend, the model James King, struts away from him and flashes her derriere.

For sure, you can smell some of the fatigued intimacy of Nan Goldin and some of the queasiness of Larry Clark in these shots. Like those photographers, Sorrenti preferred subjects who are uninterested, maybe indolent, a little sweaty. He liked to shoot full-frame, giving them heroic stature. When the photos aren’t elegiac, they can be overly blunt.

Sorrenti’s subjects, though, don’t come off as particularly observed. Flash-frozen, perhaps. The poses—when there are poses—imply what might have happened just before the shot, and what might yet unfold after it. Many of them feel almost like video stills. In Sorrenti’s mid-’90s New York demimonde, beautiful things were unfolding—the commingling of hip-hop and fashion and graffiti and skateboarding and nightlife, the last gasps of the city’s unpredictability. (And, naturally, drugs.) What a relief someone was there with a camera.

Sorrenti (his first name was pronounced “David”) died in 1997 of a medical condition that was likely exacerbated by his heroin use. He left behind a brief body of work that overemphasized a couple of crucial ideas. First, what’s happening right around you is just as beautiful as anything orchestrated by top-down taste inventors. Second, someone has to grab the camera and start shooting.

Documentary photography—in interviews, Sorrenti favored the term “reportage”—is perhaps the most social of art forms. You breathe among your subjects, hoping not to spook them. If the image is perfect, it’s something of a happy accident. The glimmering truth of the moment captured on film—back then it was film—is really just a stand-in for the assurance that the photographer was fully immersed.

Sorrenti’s photos of his girlfriend (who later took on the name Jaime when she became an actor) are among the truly outstanding images in this book, the ones that temper his vision with tenderness. Her beauty is spooky and deeply interior. In one remarkable photo, she’s ignoring invasive lighting, looking lazily off to the side with a cigarette dangling from her lips—it’s melancholy and comic and weary and suffused with raw adoration. In another, taken in Omaha on a road trip, she and Sorrenti sit side by side on a bed, with him lifting his face upward (he was small) to kiss her cheek. Both wear oversize jeans and no shirt. It’s like a decayed-halcyon reimagination of a Levi’s ad.

Both he and King used heroin, though he was sick long before it found him. Sorrenti was born in Naples, and his family moved to New York when he was young in search of better-quality treatment for his thalassemia (Cooley’s anemia), a disease in which the body destroys its own red blood cells. Sorrenti received blood transfusions every two weeks, and had to sleep attached to a machine.

He was part of an exceedingly creative family—his mother, Francesca, was a photographer; his brother Mario has been a top-tier fashion photographer for three decades; his older sister Vanina is a photographer, too.

See Know Evil, the 2018 documentary about Sorrenti’s life, detailed the ways in which his chronic illness dictated his creative choices. “He knew the older he got, the closer to the end he was, so he kind of didn’t invest so much,” Vanina said in the film. “Then as soon as he somehow owned it and put it behind him, and said ‘Hey you know what? I’m gonna live life the way that I want to, I’m not gonna live life like a sick child.’”

In addition to taking photographs, Sorrenti wrote graffiti—ARGUE was his tag—and one of the most revealing anecdotes in the book is about when he stood up to a cop who’d caught him and a friend tagging on Houston Street. “Yo Cop it’s notta big deal. . . . Its jus summer ’n’ nice ’n’ we’re painting wid deez dope colllors,” he said. (He spoke fluent cool-kid; the quote attempts a sort of dialect transliteration.) The charm worked—the cop let them go. Several pages in ArgueSKE are given over to scrawls from his graffiti black book, as well as pictures of some of his tags and throw-ups, including a particularly impressive one with melting pink and blue fill-in.

Sorrenti was making work in a moment of intense cultural upheaval and recalibration. The booming excess of the 1980s had necessitated a course correction, and culture—music, film, and more—responded with inertia, as if stupor were the only reasonable response.

In fashion, and in the photography that promoted it, that manifested as heroin chic, a gothic glamour that pushed models toward figurative (and literal) collapse. If the fashion photography of the 1980s presented clothes as both carnival and armor, and models as bright-eyed salespeople, the fashion photography of the mid-1990s presented models as, in essence, victims, and luxury as some kind of cruel joke played upon them.

When Sorrenti shot for magazine assignments, he struck a similar note of reluctance—his models cover their faces, or turn away and stare at the floor. In one shoot, he put skaters in suits, then photographed them in motion, as if for Thrasher. (In a magazine spread shown in the film, there are fashion credits for Hugo Boss and Bergdorf Goodman, and also Supreme and Zoo York—a mélange like this might be relatively common now, but at the time, it was novel.)

Plenty of the mainstream fashion imagery of the mid-’90s had similar qualities: Think Kate Moss—perilously thin, on a disheveled bed, scrunched up into a ball—for Calvin Klein (shot by Mario, as it happens). But while Sorrenti’s photographs often got lumped under heroin chic—a front-page New York Times story three months after his death proclaimed the trend over—there’s no pessimism in these images. The bodies are oddly contorted, like the shape someone would collapse into after being asked to hold a more formal pose for hours. His subjects looked sleepy, or reticent, or zoned out, but never strained. Sweetness prevails. (Some of these photos were included in an earlier chapbook, In Memory of Davide, released in 1997 not long after his death.)

He shot models like he shot his friends—while they weren’t really looking. Besides, his people were busy. The year after Sorrenti’s death, SKE Crew—Sorrenti’s group of friends—were profiled in New York magazine as emergent nightlife multihyphenate royalty, the sort of hustle that feels utterly 2020. They were party promoters and DJs and made MODELS SUCK T-shirts worn by—who else?—models. “Every day for them was a photo shoot,” Francesca said in the article. “[Davide] documented everything.”

Now, too, in every crew there is a de facto documentarian, the person capturing life while everyone else is living, or pretending to. In this current context, imagery is abundant, but documentation no longer feels like an act of astute preservation, seizing hold of something that won’t always be there. In fact, even photographing poorly is a kind of flex—access is the raison d’être, imagemaking comes second. (You see some of this in Gunner Stahl’s recently released rapper-snapshot book Portraits, which is fine—his Instagram page is better, and his simple style is better suited to tight squares and bright phone screens.)

The presumption of great reportage is that it captures something unvarnished. But the tools of imagemaking and dissemination have all but eradicated that possibility. People—the actual famous, internet famous, and wholly unfamous alike—are more aware than ever that they might be captured at any moment.

In a way, this is the world that Sorrenti was imagining. Rather than wait to be handed beauty, he lay in wait for it, snapping it when it roamed by. These days, the possibilities for such happenstance grace are theoretically limitless. But look around—everyone is always posing. There’s barely anything worth shooting.

Jon Caramanica is a pop music critic for the New York Times.