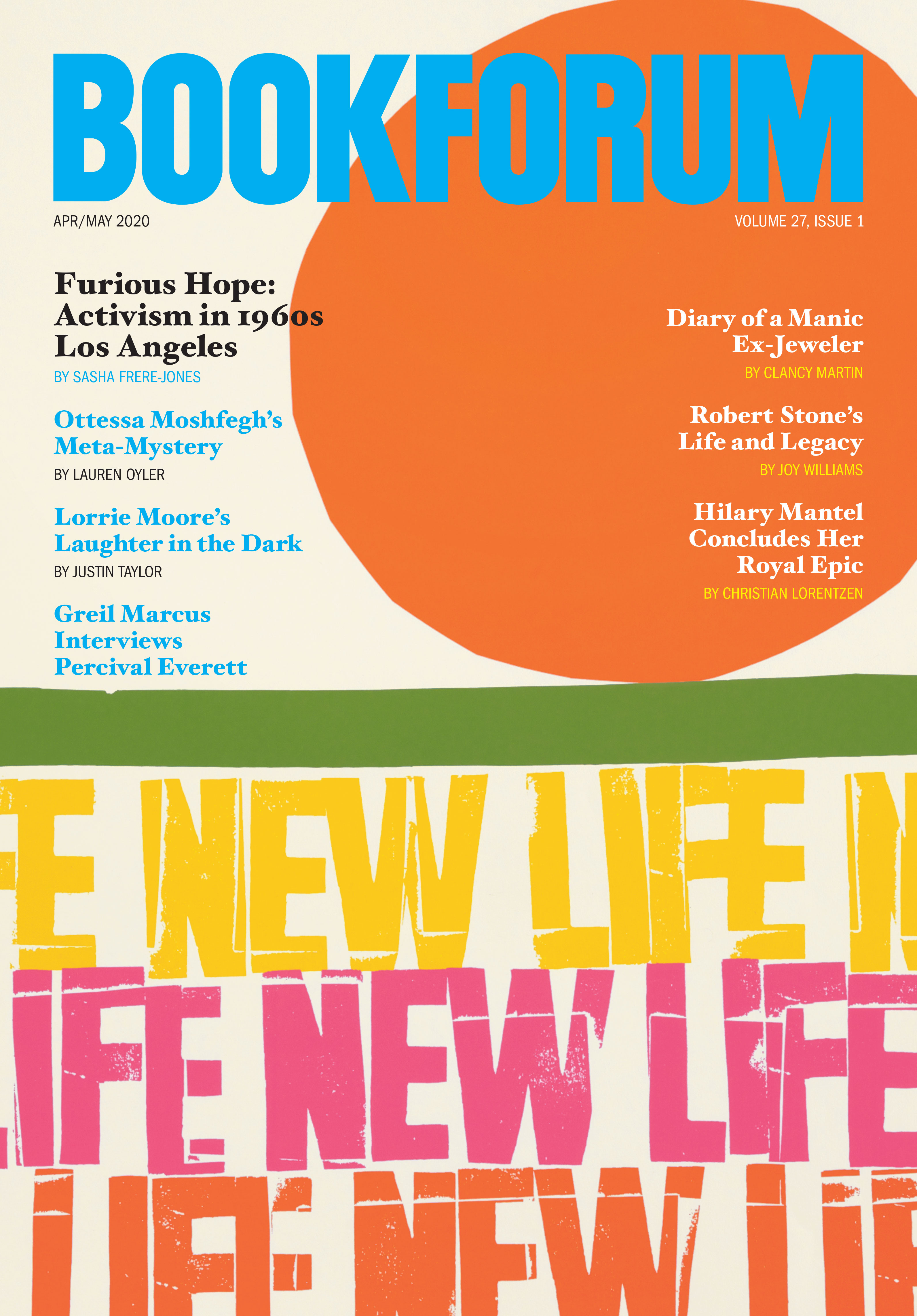

Ottessa Moshfegh is known for lacing her fiction with grossness and ugliness, for cursing her misfit characters with repugnant features, antisocial behavior, and a fascination with the nastier bodily functions. “It’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit,” she told Vice of her writing in 2015. “People love that kind of stuff.”

As the less sexy half of that quote suggests, her earlier work poses as an unflinching look at the body horror of daily life, belying the author’s bored manipulation of the fallacy that the more unpleasant something is, the truer it must be. Her sentences can seem intentionally overwritten, highly controlled but thick with exaggerated language, her ideas often illustrated with over-the-top setups that feel more tedious than titillating. After the model-gorgeous narrator of the 2018 best seller My Year of Rest and Relaxation is fired from her job at a stupid modern-art gallery, she goes outside to smoke a cigarette on her last day. Then she goes back inside, shits on the floor between two ridiculous sculptures of dogs, and puts the Kleenex she used to wipe herself into the mouth of a “bitchy poodle.”

People do love that kind of stuff, but it’s a stunty response to a stunted reality. Kate Moss taking a shit may shock the sort of people excited by bad art, but it doesn’t imply much tenderness or depth, only a basic reversal of (outdated) expectations. Yet Moshfegh’s books also contain flashes of emotional stakes, and her characters’ fairy-tale hideousness usually turns out to be a defense mechanism. Their bodies are not only repulsive but sometimes dangerous—nipples like “thorns,” “clawlike” teeth. As the title of her 2017 story collection, Homesick for Another World, succinctly communicates, physical and emotional vulgarity in her work camouflages a yearning for acceptance in a world that is difficult to like or understand. In the Booker-shortlisted 2015 novel Eileen, the eponymous narrator’s fear of erasure manifests through a self-loathing fixation on her own body. Speaking as an old woman, fifty years after most of the events of the novel have taken place, Eileen realizes she “had tried to distract myself from my terror . . . through my bizarre eating, compulsive habits, tireless ambivalence.” Similarly, the “feeling” that inspires the narrator of Rest to shit on the gallery floor is a memory of her cruel, selfish dead parents, who refused to get the family a pet. The narrator’s own clever art project, to sleep for a year by consuming a measured but overwhelming regimen of sedatives, is aimed at starting her life over, rendering her upsetting past “but a dream.”

Improbably, the scheme works: Sleeping beauty emerges from her yearlong slumber “soft and calm,” with her faith in the value of living life as a “human being, diving into the unknown . . . wide awake” restored. Moshfegh’s new novel, Death in Her Hands, also centers on a woman starting over, but where the self-protective protagonist of Rest benefits from her placement in an ironic nihilist parable, Death’s sympathetic, well-drawn narrator has the misfortune of appearing in a much subtler, more mature book—one in which suffering is developed rather than declared, its nuances articulated without ever culminating in the redemption of explanation. The sufferer is unable to confidently think her way out of her alienation, though most of the book consists of her creative, resilient attempts to do so.

Vesta Gul is a seventy-two-year-old widow, a “little old lady, according to most people,” who has recently moved east, across seven states, to a “rustic” cabin in the woods in a fictional town called Levant. She’s walking her beloved dog, Charlie, one morning when she finds a note on the ground: “Her name was Magda. Nobody will ever know who killed her. It wasn’t me. Here is her dead body.” Seeing no body or bloody evidence of one, Vesta decides not to call the police. “I would have seemed hysterical,” she tells us. “It wasn’t good for my health to get so worked up.” Instead, she begins to analyze the scene and close-read the note, spinning out possibilities.

As in Moshfegh’s previous novels, there’s something winking and unreliable about Vesta; what’s new is that there’s also a lot that’s believable and earnest about her. “If not a prank, the note could have been the beginning of a story tossed out as a false start, a bad opening,” Vesta says when she finds the message. “The story is over just as it’s begun. Was futility a subject worthy of exploration?” Moshfegh seems to be moving toward a novel within a novel, and indeed, Vesta’s lively speculations make their way into the text at length, woven with details about her past. Once she imagines a possible element of the alleged murder, it settles in her mind as part of the crime’s genesis, even if she’s come up with it through random association or transposed it from some feeling or event in her life. She decides a young boy named Blake left the note because “the name was sneaky and a bit dumb, the kind of boy who would write, It wasn’t me.” She also sets up a vivid backstory for Magda, who sounds like a character out of Moshfegh’s work: a caustic Belarusian teenager with shaved eyebrows and chipped nail polish, who has overstayed her summer work visa to avoid returning to her abusive, alcoholic father.

Soon enough, a novel within a novel appears imminent: Vesta clicks on a banner ad for “TOP TIPS FOR MYSTERY WRITERS!” while using the internet at the library. (Her original intent was to ask Jeeves questions like “Is Magda dead?” but she gets sidetracked impulse-ordering a pitch-black bodysuit, designed for hunting at night.) Though Vesta dismisses the TOP TIPS as “all prescriptive”—she finds most books unsurprising—she decides to fill out the character-profile questionnaire from the website, and she follows a suggestion to make a list of murder suspects. Here we see her freewheeling creative process at work. Among the suspects, she says, “one must be some sort of monster, some ghoul, some dark, scratchy thing that leapt out of the shadows, a figment of rage representing the dark subconscious of all of mankind. . . . As I wrote the word ‘ghoul,’ my hand slipped on the paper and the u elided with the l, making a single character that resembled the letter d.” Naming this figure Ghod, she feels “very clever in seeing the subtle meaning of the name, so close to God,” but we can also deduce that the original spark of inspiration must have come from the locals’ insulting tendency to mispronounce Vesta’s last name as “GOOL.” Later, while working in the library, Vesta spots The Collected Works of William Blake and opens it to an underlined poem. It must be a clue from her Blake, with the dumb name.

Until now, the reader has likely maintained two broad suspicions about the structure of Death in Her Hands: either that the book will eventually be revealed as a mystery novel Vesta has written herself, or that Vesta’s literary instincts are a personality quirk that will help her solve the crime. But Moshfegh makes it increasingly clear that this is not a pat thriller with a big, twisted aha, but something more unwieldy—an actually surprising fusion, or confusion, of the levels of the text. As Vesta determines the plot and characters of the “murder mystery” she’s writing and/or living in, we learn a lot about her isolated present and her circumscribed past. Memories of her late husband show up again and again. At first, Walter Gul, a German Turkish science professor, is invoked fondly. But the true nature of their relationship is filled out through memories that sometimes have an apparent trigger and sometimes don’t: Walter was controlling, patronizing, and manipulative. He used to tell Vesta that her eyes were lovely but her nose and mouth seemed to belong to a witch. After he died, she found “a list of girls, students at the university who had come to him for help, I supposed, and whom he preyed upon, listing everything about them that he coveted, staging mind games he could play with them to coax them into his arms and trousers.” She remembers how he used to play himself at chess, switching chairs. “This way, the psyche confronts itself,” he told her. “There is a dialogue. The mind must be spoken to, Vesta, otherwise it starts to atrophy.” Vesta is skeptical: “But if the mind talks to itself . . . isn’t it just saying what it wants to hear?”

Walter’s exercises in futility always seemed purposeful and productive; Vesta’s, we come to realize, are less deluded, yet this only seems to generate more madness. She can’t quite write Walter out of her own elaborate self-dialogue, even when it causes her to break down—a real breakdown, not a caricature, which Moshfegh paces beautifully and recursively. She allows the reader’s skepticism of Vesta to build by accumulating coincidences, impossibilities, and overdeterminations until Vesta recognizes that she, too, has been playing herself. The story within the story, the story within that story, and the story itself all fall apart. Misdirections are never straightened out. Details remain unexplained. Chronology mutates. The only logical conclusion is that Vesta dreamed all this up—maybe even Walter is a fabrication of a fabrication—but instead of becoming the author of her own existence, she remains trapped in her mind. While she’s resisted becoming an old witch who lives in the woods, refusing to conform to the boring frameworks of most books, she also feels it’s too late to write her own story. A younger woman, even one with as bleak a life as Magda’s, has more prospects. “Oh, I’d been deprived of so much by falling in love with my husband,” she says, finally allowing herself to get truly upset. “And now I was ruined, an old lady with a mouth full of dirt.” She’s tripped and fallen on a delivery package—Chekhov’s pitch-black bodysuit.

When Walter was dying, Vesta tells us, she begged him to send a sign from the afterlife, and he head-pattingly promised to do so. Beneath Vesta’s willingness to see patterns everywhere is a desperate search for meaning, and a knowledge that no matter where she looks, whether in love or literature, it’s always going to elude her. Even Charlie can’t be counted on. Just when she needs him most, he runs away and turns feral—a dark, scratchy thing that leaps out of the shadows. Or maybe she never had a dog. I don’t know which is worse.

Lauren Oyler is a writer in New York.