At one point it was my good fortune to spend four summers working in Tuscany, surrounded by its heritage of religious art, and by the last visit, it occurred to me I was in possession of the kind of touristic cultural education I remembered Lucy Honeychurch pursuing in Florence, in E. M. Forster’s novel A Room with a View. Italian religious art plays a role in the plot, especially a scene in which Lucy faints by the Arno, and once I came to recognize the saints’ names and the biblical characters, and the signs that this or that patron had had himself or herself painted as this or that Roman or Greek god, the novel’s setting, as well as the novel, suddenly became legible to me.

What had surprised me on those trips was how often I found myself snapping photos of details within the art—backs, hands, feet, torsos, buttocks—capturing the erotic nature of Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa, say, or the odd tenderness in how Bandinelli sculpted Hercules’s hand laid in Cacus’s hair. I will always remember the bare heel of a man, extended from behind to a viewer of a mural at Santissima Annunziata, a trompe l’oeil effect I can close my eyes and still see vividly, the beautiful bare heel among the many human figures. It was like spotting a foot amid an orgy.

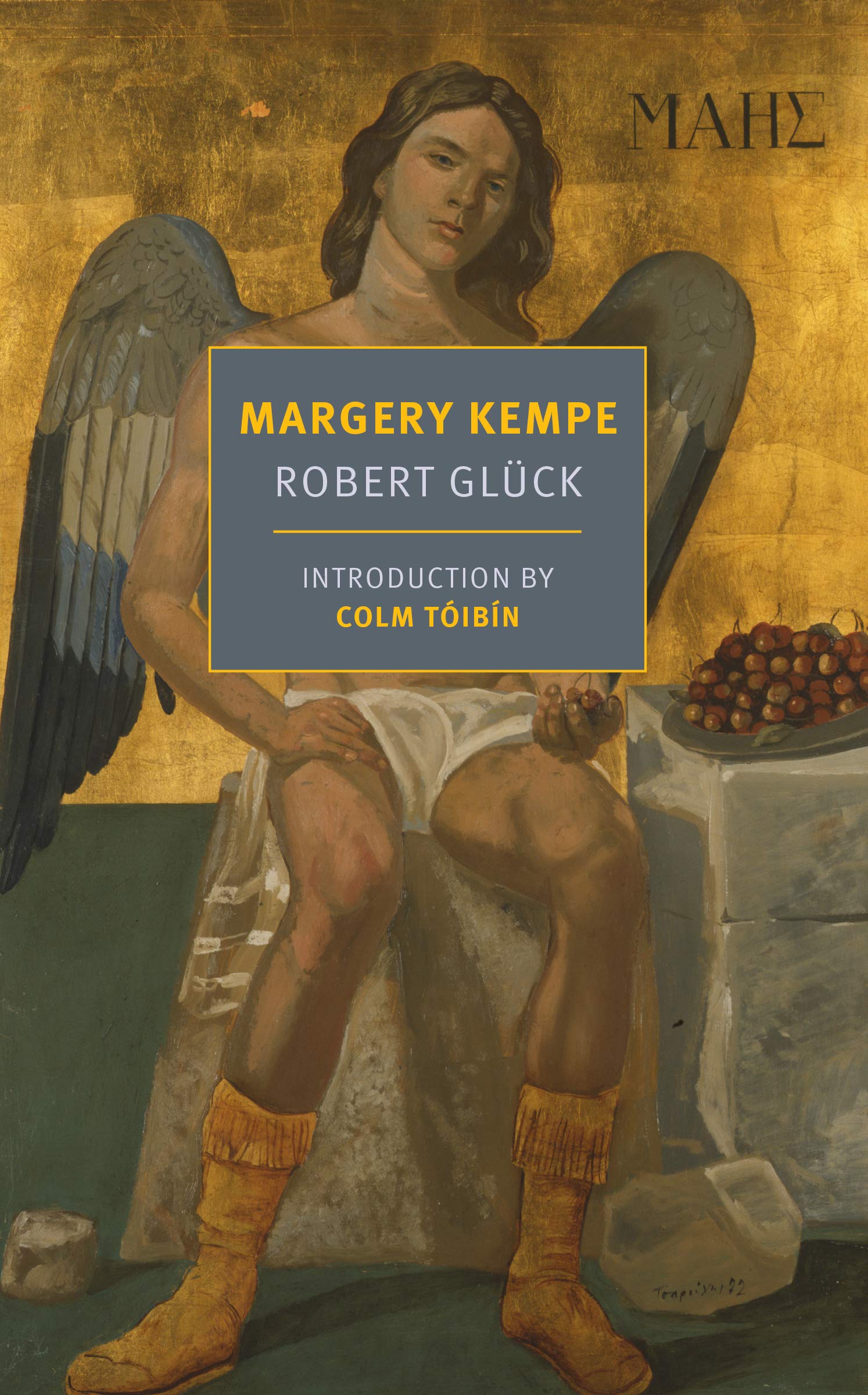

I began to wonder what it would have been like to have grown up in a religious tradition this erotic. I had been a half-hearted Methodist as a child, and my Jesus had always worn a shirt. I had never imagined the sacred nipples, much less prayed in their direction. When I think of how to tell you about the experimental 1994 novel Margery Kempe, which is now being reissued by New York Review Books, I want to begin by saying that its author, Robert Glück, has thought about those sacred nipples. He’s also reached out to twist them. Using the fingers of Margery Kempe.

Glück sets up the novel’s alternating current in the first two lines.

Can I interpret Love’s canceled flights with only the language of canceled flights, his delayed arrivals with the language of delay?

In the 1430s, Margery Kempe wrote the first autobiography in English.

The novel is offered as if it is both itself and the notes for how it becomes itself. Glück’s erotic fantasy of the fifteenth-century Englishwoman Margery Kempe blooms on the page alongside a contemporary story of his relationship with L., his elusive younger boyfriend in San Francisco. Glück writes as if he is imagining what it would feel like, even now, to be the first person to write an autobiography, as if by following Kempe he can conjure that same magic. “I fought for meaning, now I have too much of it. I disappear from a position too full or empty to reveal the extent of my need. I’m Margery following a god through a rainy city. The rapture is mine, mine the attempt to talk herself into existence.”

Glück confides, in the book’s third chapter, that he has been thinking of writing about Kempe for twenty-five years, more or less the same age as L., who jokingly calls Glück and his circle of author friends “The Writers Who Love Too Much.” We move rapidly from the contemporary—the 1980s or early ’90s—to the fifteenth century and back again. The result is not historical fiction but something that has more in common with Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red. Kempe is not quite a mask for Glück but a way to think about how to write about what he is feeling. Not an allegory but a stalking horse.

Much like in A Room with a View, Margery Kempe imagines in sublime detail the erotic awakening of a middle-class woman. Margery is no girl hoping to learn about art but something of a medieval saint manqué. A former flirt and materialist who bought her way out of her marriage after giving her husband fourteen children, she was determined to pursue her path to sainthood, and traveled widely in the process, from Santiago de Compostela to Jerusalem. After many pilgrimages, she dictated her autobiography—as she, like most women then, was not educated—and so it is that an illiterate woman came to write what is considered to be the first autobiography written in English. Kempe details her life, her travels, and her sexually charged visions of Jesus. An excerpt appeared in pamphlets in 1501, but the full text was not published until 1936.

Glück’s story about Margery takes her visions and unfolds them, with an immediacy and an erotic power and scale reminiscent of Giorgio Vasari’s stunning mural on the inside of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral in Florence. It is like falling upward into a long dream about sex and Jesus, in Glück’s hands a spectacle, visceral and sublime.

Margery spent two years in a state of arousal and despair. Jesus was a wish. She waited actively as though feeling the air quicken before rain, imminent saturation. His translucent skin—a milky wash over a base coat of gold dust. She conjured long conversations tremulous with sincerity and avowal—or he was describing her to Mary or God. She sat up and looked around, surprised he didn’t appear in the creak of an opening door.

The immediacy of Margery’s character, and the way Glück becomes possessed by it, has some of the offhand directness of his novel Jack the Modernist, but a new poetic force rings also. The force, perhaps, he has been pursuing in Margery, and with L. Reading the sex scenes with Jesus, written in this language, I was reminded of the kind of sex that feels like one is building a new world, learning the ways of the body as if it has just been born. But I also loved the scenes of ridiculousness between people who have just had sex, the quieter postcoital interludes.

Jesus perched naked on a banquette, eating a pear tart, rejoicing in bland fragrant sweetness. He offered a slice to Margery, who never refused pastry. He tucked his cock between his legs and wore a flushed, mocking face. He crossed his legs tighter, displaying only sparse brown hair. The ground slid away; Margery’s dirty laugh hovered over an empty space because the joke was against her.

As these two stories stipple each other and intersect repeatedly, they yield the reinventions that love, obsession, and sex make possible. These reinventions are the novel’s real subject. Not just the suffering and the ecstasy, but also the creativity that accompanies them.

Glück was a cofounder of and central figure in a literary movement called New Narrative, which included writers such as Dodie Bellamy, Kevin Killian, and Kathy Acker. In his 2004 essay “Long Note on New Narrative,” Glück lays out some of the central questions he and his West Coast queer writer friends were working on, as they tried to remake writing to accommodate their sense of their own existence in the face of what felt like the alienations of Language Poetry and the American literary avant-garde of the 1970s.

How to be a theory-based writer?—one question. How to represent my experience as a gay man?—another question just as pressing. These questions lead to readers and communities almost completely ignorant of each other. Too fragmented for a gay audience? Too much sex and “voice” for a literary audience? I embodied these incommensurates so I had to ask this question: How can I convey urgent social meanings while opening or subverting the possibilities of meaning itself? That question has deviled and vexed Bay Area writing for twenty-five years. What kind of representation least deforms its subject? Can language be aware of itself (as object, as system, as commodity, as abstraction) yet take part in the forces that generate the present? Where in writing does engagement become authentic? One response, the politics of form, apparently does not answer the question completely.

These questions cast long shadows. The best writers I know are struggling with at least two of these questions today. Much of what Glück speaks of in his essay could be used to describe Margery Kempe. The two narratives become one, feed each other, much in the way lovers feel they are made possible by the presence of a beloved. As Glück writes later in “Long Note on New Narrative”:

We were thinking about autobiography; by autobiography we meant daydreams, nightdreams, the act of writing, the relationship to the reader, the meeting of flesh and culture, the self as collaboration, the self as disintegration, the gaps, inconsistences and distortions, the enjambments of power, family, history and language.

Reading the essay, we’re asked to imagine a time when such discussions were fringe. This new edition of Margery Kempe, then, returns to a literary world changed by these questions and their answers, a world that Glück helped make.

The twinned narratives in Margery Kempe reach their twinned relative climaxes: Margery, abandoned by Jesus, goes on alone, and Glück, having offered an ultimatum to L.—asking him to move in with him, or part ways—finds he must give L. up. As we descend the stairs Margery makes of Jesus and his rejection of her, and enter the final pages, we re-experience the novel as a critique. “A woman famous for her tears turned a corner in the 1430s and wrote the story of her life.” Glück becomes her literary intercessor. “She turned her second-rate obsession into her last bid for endless response, a self asserted just as the world withdrew its support. She fell for so long she lost the sensation.” And we, through Glück, regain it here.

By the end, Margery Kempe felt to me like a mingling of Vita Sackville-West’s biography of Joan of Arc and the sort of pulp gay erotic fiction I found in porn stores in the 1980s—the illustrated covers feathery from years of being held, read, and put down—and yet also somehow firmly within the tradition of any mural on any church or cathedral in Florence. If it’s sacrilege to imagine Jesus as an object of desire, as the first Margery Kempe did, then Glück’s novel has a great deal of company, in both the past and the present.

Alexander Chee is the author of The Queen of the Night (2016) and How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (2018, both Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).