APRIL 21, 2020. Last night, the crazed leader announced that he wants to ban immigration. Today I was told to prepare for furlough at my job, and I spoke to my friend who cannot get her cancer treatments. Down the road at the hospital, they are still forklifting corpses into refrigerated trucks. The price of oil has tanked. Around the corner someone has painted these words on the side of a mailbox: PROTECT BLACK PEOPLE. COVID-19. The midwife who delivered my children is begging for masks. All of the mom-and-pop shops have shuttered. The streets are littered with discarded blue surgical gloves in gestures of sign language. Half of the neighbors in our building have fled the city. Some of them gave us their keys before they left, asking us to put their packages and mail inside their doors. But the packages are being stolen from the lobby, where sits an off-brand two-gallon dispenser of hand sanitizer. Among the neighbors who remained, one was taken out on a stretcher, presumed victim of the virus, one had a baby girl, one plays the saxophone, one refuses to ride the elevator with us any longer, one still allows my children to pet her dogs, one baked my family a lemon cake, several lost their jobs, and all of us hang out of our windows daily at 7 PM, like animals in cages, to clap and bang pots for the workers who give us life.

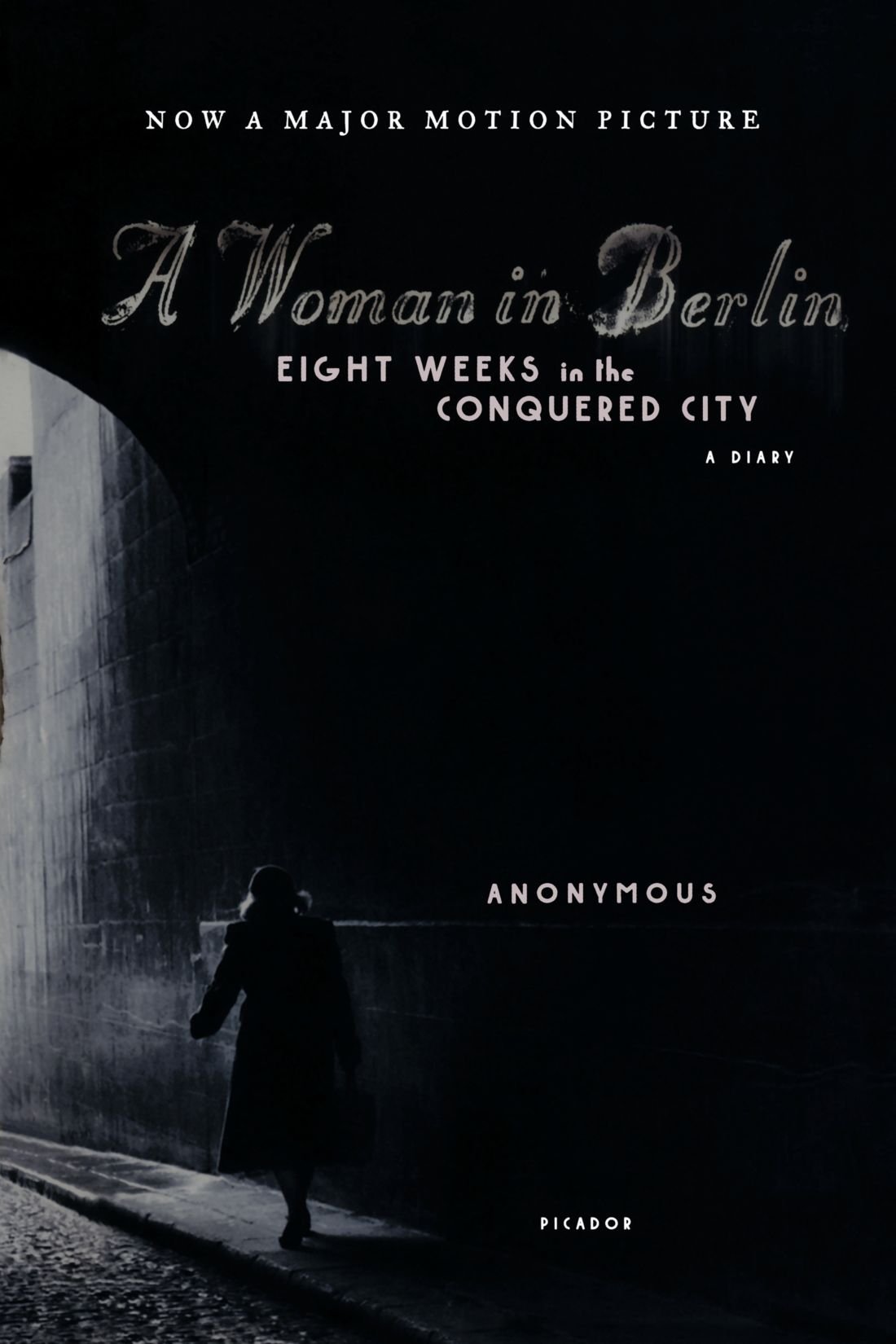

Once I’ve finally gotten the children down to bed after undifferentiated days of homeschooling, worrying about the unknowns, waiting on long lines with other trampled ordinary masked New Yorkers outside the bodega or the pharmacy or the bank, rummaging in the recycling bins for paper, which we have run out of along with so many other provisions, cooking, cleaning, clamoring in the cacerolazo, I collapse in the yellow armchair overlooking the George Washington Bridge, plug my ears against the ceaseless onslaught of sirens, and take out the book. What an uncanny time warp it feels, under quarantine in New York City in April 2020, to be reading about the hellscape of April 1945, as described by the anonymous diarist of A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City. It is not an escape but a dark mirror.

Among other familiarities is this: a demagogue who would sacrifice his most vulnerable citizens for the obstinate delusion of empire. At the time that the book’s author, a thirty-four-year-old journalist, took meticulous notes on the fall of her city to the Red Army, she was one of two million citizens in Berlin. Most of them were women and children. True to inhuman form, Hitler rejected proposals to evacuate them while there was still time, brazenly disbelieving that “there were 120,000 babies and infants left in the city and no provisions for a supply of milk,” as reported to him by Berlin’s military commander. (There were also no newspapers, no electricity, no gas, and little food.) Leaving civilians behind would force the bedraggled German troops to defend the city more courageously. That was the logic. If they flew the white flag of surrender, they would be shot.

The diary begins on Hitler’s birthday, April 20, four days after the opening attacks. Nazi flags were hoisted over the rubble of the city center, where the US and Royal Air Forces had destroyed 90 percent of the buildings. Nobody is duped by the propaganda ministry’s promises of victory and a bright future—least of all the diarist, whose tone is shrewd and wry. “Doesn’t look much like . . . a Blitzkrieg anymore,” she writes of a skeleton crew of tired old German soldiers carting hay. Deference to the Nazi regime had withered by this stage of the war. Soviet tanks start encircling Berlin after smashing their way through German defenses. Long-range artillery shells land in the suburbs that night.

A Woman in Berlin covers the period of bombardment, street fighting, Hitler’s suicide, the Nazis’ surrender, and the occupation of the city by Soviet conquerors. Its earliest entries are expressions of confinement from the basement where the author and her neighbors seek shelter from air raids, artillery fire, looters, and rape. Their most immediate anxiety is what will happen when the Russians arrive. “Our fate is rolling in from the east,” Anonymous writes. “It will transform the entire climate, like another Ice Age.” My sentiments exactly.

On April 27, the Red Army reaches her street, and soon after the troops start billeting and rolling through, the real horror begins. Along with at least a dozen women and girls in the apartment block where she lives, the diarist is claimed as a spoil of war, repeatedly and mercilessly raped. The diary, then, is not only a testimony of war’s atrocious aftermath, when material and social scaffolding have caved, but also a mechanism of survival. What I find most remarkable about the writer is her dispassion. She is unfailingly calm in her indictment of this hell. Not a hint of self-pity. She says it herself: It’s the writing that saves her—the act keeps her sane in a time of havoc and moral collapse. “Slowly but surely we’re starting to view all the raping with a sense of humor,” she writes. A chestnut of her gallows humor, after finally managing to wash her sheets: “A much needed change after all those booted guests.”

Why am I reading this book, of all books, at the epicenter of a global pandemic? It does not offer solace, analysis, forgiveness, condemnation. Nor does it provide insight, except for this lesson: It is not my duty today, as a writer in free fall, to do anything but chronicle the absurdities of a falling empire.

Emily Raboteau is a long-form essayist and professor of creative writing in Harlem at the City College of New York. Her most recent book is Searching for Zion (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2013).