In the twelfth century, the city of Cahokia, settled on mounds near the Mississippi River, had a population greater than London’s. Its trade and travel routes stretched to present-day Minnesota and Louisiana. Around 1350, Cahokia’s residents abandoned the city for unknown reasons, but its traces remained. In 1764, traders led by Auguste Chouteau built a fort across the river and saw the abandoned mounds. Assuming they were the remains of a long-gone civilization, the French traders thought the people living around them—a different group of indigenous people than Cahokia’s inhabitants—were colonizers. Chouteau’s men believed they had as much right to the land as the living indigenous people. They held onto this belief to justify seizing the land and developing the trading post into St. Louis.

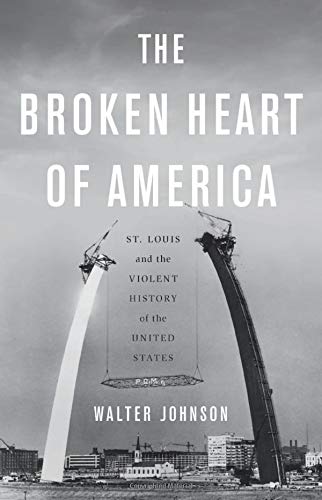

In The Broken Heart of America, his new history of the city, the Missouri-born historian Walter Johnson tracks the ways white settlers have imagined their right to land and exploitation from the eighteenth century to the present. The imagination’s relationship to material conquest is not a new subject for Johnson. His first book, Soul by Soul (1999), examined how participants in a New Orleans slave market wrote and rewrote the relationship between race and slavery. His 2013 history of the Mississippi River basin, River of Dark Dreams, depicted the future envisioned by antebellum white Southerners who hoped to claim parts of the Caribbean and Central America as slave states. Building on this analysis of American imperialism and white ideology, The Broken Heart of America explores how Chouteau and his successors’ belief that the land surrounding St. Louis belonged to white people shaped the city’s, and the country’s, future.

This belief was made real only through violent conquest. In the early nineteenth century, St. Louis, the westernmost outpost of the new United States, was the center of military campaigns to remove American Indians from their land. Its white settlers used tactics honed on Indians—removal, land expropriation, and murder—on enslaved and freed black people. When St. Louis’s marginalized formed alliances across the color line in the late nineteenth century, local politicians bought the allegiance of some and attacked the rest. Lesser writers might tell this story as though the oppressed were solely objects of state violence. But Johnson, under the influence of historians such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Cedric Robinson, and Nell Irvin Painter, describes state repression while emphasizing the gains made by the victims of that repression. He argues that violent oppression emerged in response “to the consequential efforts of conquered, stigmatized, poor, and radical people.” The dispossessed fought for their future, in other words, and were killed for it.

“Viewed from St. Louis,” Johnson writes, “the history of capitalism in the United States seems to have as much to do with eviction and extraction as with exploitation and production.” Today, the city has the highest murder rate and rate of shootings by police in the US, and poverty permeates its black neighborhoods. But this history also birthed a tradition of radical organizing, from the 1877 general strike to the Black Lives Matter protests, that Johnson believes will one day reclaim the city.

St. Louis became part of the United States in 1803, when Thomas Jefferson purchased the western territories from France without consulting the land’s indigenous inhabitants. From the city, he hoped to trade with indigenous people to “run [them] into debt” so they would cede their land to settle their bills. The following year, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set out from St. Louis to survey the territory for its mercantile and imperial potential, relying on indigenous knowledge of routes and the land along the way. After their return, Jefferson appointed Clark the superintendent of Indian affairs, an office stationed in St. Louis, and Clark encouraged both the fur trade and the taking of Indian land. As military headquarters for the US Army’s Western Department, St. Louis became the front line for a settler colonial war. Clark and the office of Indian affairs, in turn, claimed approximately 419 million acres and exiled roughly eighty-one thousand indigenous people from their land.

The acquisition of new holdings raised the question of whether they would be designated as free or slave territories. After the Missouri Compromise ensured that Missouri would be admitted to the union as a slave state in 1820, its senator Thomas Hart Benton became one of the foremost advocates for slavery’s westward expansion. Benton and others like him saw indigenous genocide as the means for acquiring land and the expansion of slavery as the means for cultivating that land. “Genocide was the vanguard of the empire,” Johnson writes, “and anti-blackness followed immediately in its wake.”

In the decades before the Civil War, St. Louis became the headquarters for state violence against both black and indigenous people. After the Black Hawk War of 1832, in which the leader of the Sauks evaded capture for months, a US military battalion based in St. Louis murdered indigenous people to make examples of them. The city’s proximity to Illinois and the states of the former Northwest Territory, all of which had outlawed slavery, made it the site of “low-intensity open war” against enslaved and freed black people. The conflict escalated after the Supreme Court took the side of the enslavers in the 1857 Dred Scott case, named for the plaintiff, a St. Louis resident, and extended the rights of slave owners to free states.

The vanguard opposing slavery was a coalition of white immigrants and enslaved people. In St. Louis, the new Republican Party, founded on an antislavery though pro-settler platform in 1854, was radicalized by German immigrants arriving from Europe after supporting the 1848 anti-monarchist revolutions. Following Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, armed antislavery militias spread throughout the city. The beginning of the Civil War the following year, Johnson writes, offered non-wealthy white people “an unprecedented, even revolutionary alternative: to ally themselves with the slaves and overthrow their masters.” For many who enlisted, the war to preserve the union was a war for freedom. When a Confederate militia gathered to seize St. Louis’s arsenal (the second largest in the nation), the Union army deployed several regiments, one led by Henry Boernstein, a publisher of Karl Marx. After emerging victorious, many of the same Union army soldiers waged war across Missouri. Counter to Lincoln’s orders—and two years before the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation—they encouraged enslaved people to flee and seize their freedom.

Fearing the radical potential of interracial solidarity, wealthy whites went to great lengths to consolidate their control over the city after the war’s end. In the years before the expansion of the vote to all men in 1870, German immigrants were coaxed away from radicalism by an amendment to the state constitution granting all (and only) white men the franchise. Suffrage, however, provided only temporary stability. The coalition of the war years reemerged in the city’s 1877 general strike, when a railroad strike in the East set off work stoppages all across St. Louis. Black and white workers took over the city government and demanded an eight-hour workday and an end to child labor. Strikers reopened the flour mill to provide bread for the people. “It is wrong to call this a strike,” complained the Missouri Republican, “it is a labor revolution.”

The rebellion was quelled with the help of the city’s police, a citizens’ militia, and federal troops. The defeat tipped the balance of power toward the city’s white elite. As St. Louis became a crossroads for trade and a center of industrial production, the white upper class consolidated its dominance. Nowhere was this more evident than the 1904 World’s Fair. Attended by Woodrow Wilson, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Mark Twain, among others, the fair celebrated the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase. True to its imperial roots, it hosted the largest human zoo ever assembled in world history, displaying prisoners including the Apache leader Geronimo, the enslaved Mbuti Ota Benga, and Filipino people captured in the Pacific war. The zoo was horrifying in and of itself, but it was also an appalling symbol: The city’s ascendancy depended on, justified, and escalated American imperialism.

In the early twentieth century, increasing black migration to St. Louis spurred a new wave of poor people’s organizing. Some came to the city fleeing the South. Others ran from East St. Louis, just across the river in Illinois, after one of the decade’s deadliest massacres of black people took place there in 1917. Upon arrival, they found labor and residential segregation, ensuring that black people made less money and paid more for smaller living spaces than their white peers. As poverty worsened during the Depression, poor black people joined their white counterparts to protest. In 1932, marchers led by fifty black women stormed the mayor’s office; the city then agreed to distribute thousands of dollars of food to its residents. In the same era, middle-class black people waged, and sometimes won, legal battles against housing and education segregation. Through organized struggle, they tried to build a future where they could flourish.

Their gains were not evenly distributed. During the Second World War, black people fought to integrate the defense industry, with some degree of success. In 1944, fearing the war’s end would mean mass job loss, black and white organizers advocated building dams on the Missouri River to provide work and water for valley agriculture. “As visionary as the scheme must have seemed to labor activists in St. Louis,” Johnson writes, “it was framed by the same imperialist blinkers that had narrowed the vision of many of the nineteenth-century radicals.” The dams flooded indigenous people’s reservations, once more trading their lives and land for St. Louis’s economic future.

If the destruction of Indian land harked back to an old model, so too did efforts to reverse black residents’ progress. This conflict had been brewing since before the war. Harland Bartholomew, the city planning commissioner who would later be called “the father of American urban planning,” used zoning to remove the city’s black residents. Claiming that destitute neighborhoods would spread throughout the city, he won approval for their destruction. In 1928, Bartholomew conceived of a plan to raze and redevelop the poor, largely black waterfront neighborhood; ten years later, the mayor carried out his vision and built the park where the Gateway Arch now stands. After the war, white union workers were hired to bulldoze black neighborhoods (and one cemetery) in order to build Interstate 70 and enable the growth of white suburbs around the city. In the coming years, the city continued this process, all with an eye to shoring up the value of wealthy white neighborhoods.

Demolition could not stop the rising tide of civil rights organizing. In 1947, the sit-in movement started in St. Louis. For six years, black and white women sat at lunch counters, waiting to be served. Organizers boycotted stores that only employed white people, pushing local businesses to hire black workers. By 1953, every department store was integrated. Their progress was not just material; as the organizer Percy Green put it, “You have control over the money, but we have control over how you are going to be seen in history.”

Unsurprisingly, the state responded violently to the movement’s successes. As the decade continued, St. Louis’s notoriously brutal police force attacked black activists, even chasing some out of town, and the city continued to subject its black population to destruction and neglect. In the 1970s, politicians used the poverty of the remaining black residents as justification for federal grants and then spent the money by funding gentrification. Deregulation in the 1980s enabled larger companies to acquire smaller ones operating in St. Louis, resulting in regional job loss. In the 1990s, businesses offering payday loans with high interest rates exploited black neighborhoods, while the police targeted black inhabitants for ticketing and fines. Across the city, people profited from black residents but returned little to black neighborhoods.

Johnson’s history of profitable exploitation and its opposition is not gender-neutral. Removing American Indians, bulldozing neighborhoods, and disinvesting in black housing had disastrous ramifications on black and indigenous women. As Johnson writes,

And because removal is fundamentally about controlling the future, about determining what sorts of people will be allowed to live in what sorts of places, it is always concerned with the control of gender, sexuality, and reproduction; often women and children are singled out for particular sanction and targeted violence.

Their very precarity, however, often made black women a formidable political force. In 1969, women at the neglected Pruitt-Igoe projects led one of the first rent strikes in American history. Facing bankruptcy, the Housing Authority eventually complied with their demands. Their victory forced the state to invest in black life.

The weight of years of extraction and violence as well as the lessons from years of radical activity made the region a site of new possibilities in the twenty-first century. “The two-hundred-year history of removal, racism, and resistance,” writes Johnson, “flowed through the two minutes of confrontation on August 9, 2014,” when police officer Darren Wilson killed Michael Brown. So too did the history of resistance run through the protests and organizing of the months after. The protesters were, Johnson writes, “legatees of a history of Black radicalism and direct action as measurelessly implacable as the flow of the rivers. And still they rise.”

Surveying the long history of St. Louis, Johnson continually emphasizes that the Indian removal and genocide upon which the city depended set its course up until the present day. In his careful analysis of the ways in which violence created white wealth, Johnson joins a large body of scholars, including Robin Kelley and Lisa Lowe, studying racial capitalism. For Johnson, it is crucial to link white supremacy to its economic ideology, as both direct imperialist dispossession (such as the settling of Indian land) and capitalist exploitation (such as segregated labor). In St. Louis, the twin legacies of slavery and the Indian Wars have combined to brutal effect: Whether by exile, murder, or exploitative labor, wealth has been extracted from black and indigenous people.

Yet a persistent thread of optimism runs through Johnson’s history. Time and again, after state intransigence, St. Louis’s black residents formed non-state mutual aid projects that created what Johnson calls “actually existing socialism” by sharing resources and infrastructure. For him the city is, as the scholar George Lipsitz says, “the right place for all the wrong reasons.” Because the particularly American strain of racial violence pioneered in St. Louis has so often spread throughout the nation, the tactics its black residents developed to support black life may be ones the rest of us adopt in the coming years. The futures they have fought and continue to fight for, in other words, could well be our own.

Elias Rodriques’s writing has been published in n+1, The Nation, and other venues, and his novel is forthcoming from Norton.