The mood, when a story about Edward Snowden begins any time before the news-breaking Guardian piece of June 5, 2013, is a clean dramatic irony. We know the identity of the anonymous source; the characters don’t. The greatest secret-exposer of his generation was himself an unexposed secret that winter and spring, a cipher who insinuated his way into journalists’ lives through encrypted channels, making vague and terrifying claims that were hard to grasp and verify. He could be a liar or a catfisher. It could be a sting; you’d spend the rest of your life in jail.

Three journalists stood at the center of the mystery. The first was Glenn Greenwald, whom Snowden contacted in December 2012. Greenwald had never used encryption and found the installation process onerous, even after Snowden sent him a homemade twelve-minute Vimeo clip called “GPG for journalists,” which Greenwald apparently ignored. The second was Laura Poitras, whom encryption didn’t intimidate: After filming My Country, My Country (2006), about a doctor running for office in US-occupied Iraq, the documentarian had landed on a DHS terrorist watch list and moved to Berlin to protect her future footage from confiscation. Poitras learned GPG (GNU Privacy Guard) and started chatting with the man who identified himself as “Citizenfour.” Paranoia enfolded her. “Is it a trap,” she wrote in her diary that January, “is he crazy, or is this something real?”

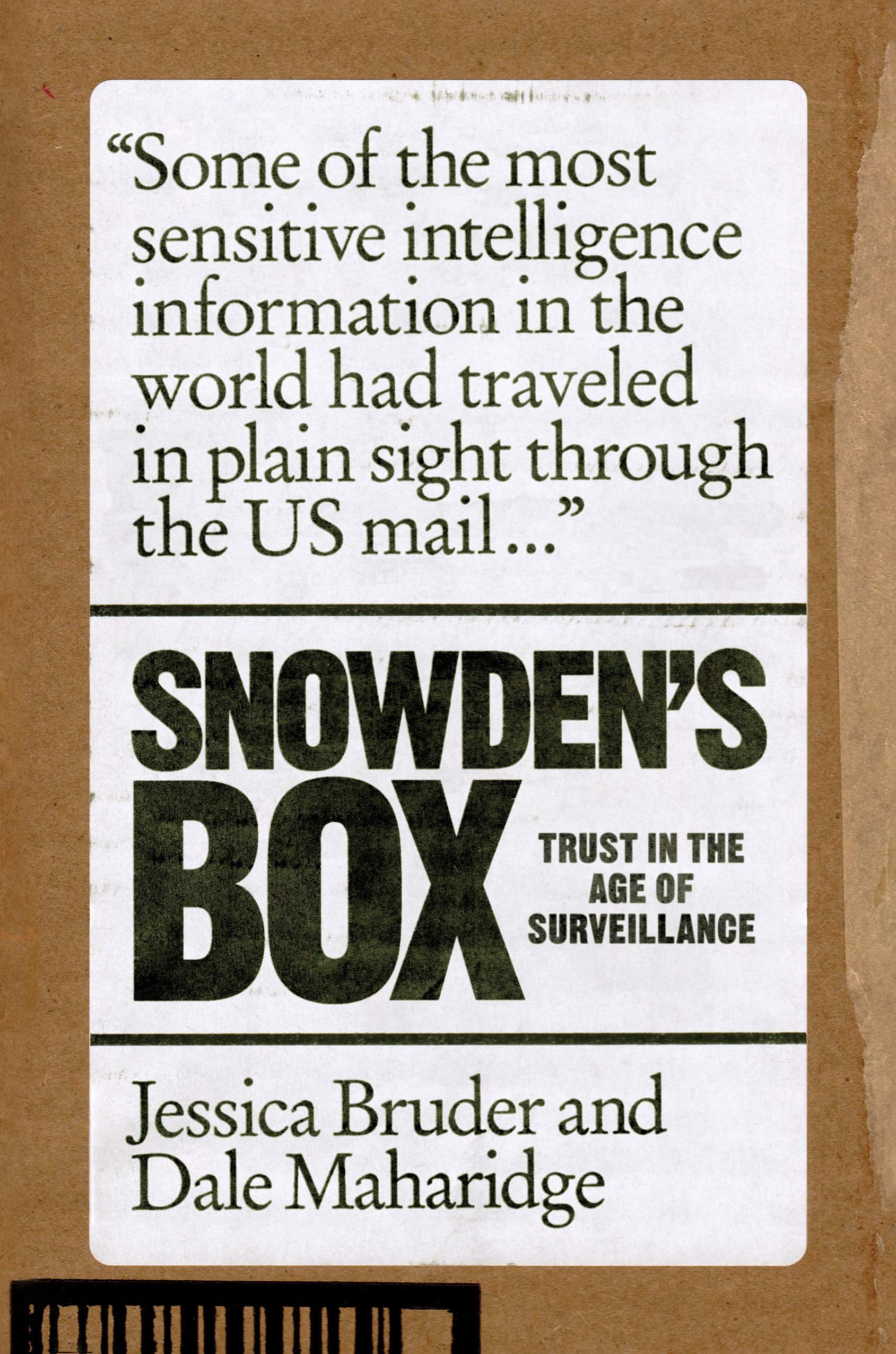

Snowden asked Poitras to receive a package via the USPS. Afraid to blaze too clear a trail, Poitras asked her friend, the journalist Dale Maharidge, to find an unlikely mailbox. Maharidge invited his friend, the journalist Jessica Bruder, over to his place in Manhattan, then asked her to put her cell phone in the refrigerator so they could talk. (People putting their phones into refrigerators is a telltale sign that Snowden’s in the air, as the footsteps of ambergris-scented courtiers betokened the imminence of Elizabeth I.) On May 14, Bruder returned to her apartment in Brooklyn and saw a Priority Mail package from Hawaii, labeled ARCHITECT MATS ENCLD, bearing—in what could only have been a fuck-you to the US intelligence dragnet—the cheeky return addressee B Manning. Inside was the kit and caboodle.

Poitras’s subsequent meeting with Snowden, in a room at the Mira Hotel in the Kowloon district of Hong Kong, was covered in her documentary Citizenfour, and the scope and significance of the revelations in the Snowden files became the basis for multiple books, including Greenwald’s grippingly self-hagiographic No Place to Hide and Snowden’s own memoir Permanent Record. Bruder and Maharidge have just brought out Snowden’s Box, about their involvement as friends and couriers to Poitras. The only person who hasn’t yet spoken at book or movie length is the third journalist who was at the center of the Snowden mystery in the spring of 2013, Barton Gellman.

Gellman is a Pulitzer winner who broke crucial stories from the Snowden files in the Washington Post, but—in my imagination, at least—he never became associated with Snowden the way Poitras and Greenwald did. This is because of the fateful decision he made not to accompany Poitras to Hong Kong, and therefore not to appear onscreen when Snowden was introduced to the planet. The frenzy of that spring and summer, along with a great deal of newsroom intrigue and record-straightening, fill the first half of Gellman’s long-awaited Dark Mirror.

It was Poitras who introduced Gellman to Snowden. He seemed a natural fit: Here was a writer with the credibility of a legacy-media career and deep sources in the national security establishment who had also demonstrated a willingness to piss people off. Gellman had written, with Angler, the definitive biography of the Cheney vice presidency. That book ticked like a bomb. It was one taut set piece after another: Cheney’s wily ascent to power, his subordination of old-guard Republican senators, his role in the expansion of the surveillance state after 9/11. And Angler was on shelves in 2008. Which meant that Gellman had been talking about FISA courts running amok while Snowden was still a twenty-five-year-old CIA contractor in Geneva.

Gellman had his first exchange with the source he knew as Verax on May 16, 2013. (Greenwald was in Rio de Janeiro without encryption turned on.) But as the Hong Kong trip approached, Gellman became mired in preparing his first Post story. He still needed to authenticate some of the documents. And—in a ritual that may seem deranged to those outside the profession—he needed to give the government’s lawyers a chance to try to persuade him not to publish. There was no way to accomplish these tasks without a digital copy of the files; there was no way to keep the digital files protected if he brought them into “the backyard of the Chinese Ministry of State Security.” Fearful both of aiding a US enemy and of opening himself to prosecution by the Department of Justice, Gellman tells Poitras and Post editor Marty Baron that he will stay at home in the US.

This incites a desperate hunt for his replacement. An independent filmmaker without institutional support, Poitras had been counting on the company of a journalist with a paper behind him. Now everything’s in chaos. Snowden learns of the delay and is frantic; he fears he’s been abandoned. Ben Wizner, Snowden’s lawyer at the ACLU, sets up a meeting between Poitras and David Remnick of the New Yorker so she can pitch the story as a scoop for one of the magazine’s star national security reporters, Sy Hersh or Jane Mayer. But Remnick doesn’t bite. As Snowden’s Box recounts:

Remnick wanted direct access to the trove of documents, which Laura would not provide. Without knowing more, he wasn’t prepared to dispatch a reporter to Hong Kong on what could have been the mother of all wild goose chases. Frustrated, Laura shut her laptop and left.

Only then does Snowden make a last-ditch run at Greenwald and share some of the classified documents with him. Greenwald snaps awake, gets a Guardian assignment, and is off to Kowloon. His scoop about Verizon giving the NSA access to cell phone records beats Gellman’s first Post article. This is the inverse of the story about Waylon Jennings offering the Big Bopper his seat on Buddy Holly’s charter plane on that dark night in February 1959. This is one flight that Gellman should have taken.

Or maybe not.

One of the main arguments of Dark Mirror, you might say the book’s organizing principle, is the worthwhileness of the kind of journalism that Gellman practices and that—Gellman argues—writers like Greenwald do not. I believe this is a firmly held conviction, but it also serves as a product-differentiator. Gellman’s book was first announced in catalogues in 2016, three years before Permanent Record. Whatever the reason for delay (a Penguin Random House spokesperson didn’t know), delay there was. You don’t want to bring out an “authoritative” take on a subject after that subject has just published a great book literally titled Permanent Record. (Snowden’s collaborator was the novelist Joshua Cohen, and one way to view PR is as an easy-drinking Cohen novel.) It would be as though Cheney had turned against Bush, cowritten a fleet three-hundred-pager with Michael Lewis, then dropped it two weeks before Angler. Front table of every Hudson News in the country.

The story is so well known that we amateur Snowdenologists can recite the plot points from memory, like favorite songs: the fractured tibiae that end our hero’s basic training in the Army, the Rubik’s Cube in which he practices smuggling the memory cards out of the NSA substation at Hawaii, the “Saudi wealth manager” whose entrapment on DUI charges by CIA agents in Geneva turns the hero queasy about “human intelligence” spying. For those who don’t like reading, there’s the Hollywood movie; for those who aren’t of age, I’m told a young-adult version of PR will shortly drop in Germany. If I’m walking on West 45th Street one day and see a marquee for Snowden: The Musical, choreographed by Twyla Tharp, I will not even break stride.

Therefore Gellman must propose something more than a reheat. “What emerges here, I hope,” he writes in the preface, “is an honest portrait of investigative reporting behind the scenes.” Then comes the distinction:

Snowden is a complicated figure. . . . Our relationship was fraught. He knew that I would not join his crusade, and he never relied on me to take his side as he did with Laura Poitras and Glenn Greenwald. We struggled over boundaries—mine as a journalist who wanted to know more, his as an advocate who saw his cause at stake in every choice of words.

Gellman wants us to know that he’s not in the pocket of Big Snowden, and he flaunts his independence throughout Dark Mirror. One of Snowden’s early claims to Gellman was that “on the authority of nothing but a self-certification made to a software program, I have wiretapped the internet communications of Congress’ current Gang of Eight and the Supreme Court.” This wasn’t true. In fact, as Gellman shows, Snowden had merely pulled up some of Nancy Pelosi’s emails by feeding her publicly available @mail.house.gov address into an NSA search tool. He believed that he could have tapped the justices but never did. You can see why Gellman cares about this as a journalist. You can also see why Snowden would have made an exaggerated claim as an instrument to attract attention, when he was sitting in his house in Hawaii with stolen materials, terrified his leaks would land in a void and he’d land in prison for nothing.

Sometimes it’s hard to know what to make of these anecdotes. At one point, Snowden wants Gellman to rush publication of a document with a unique identification code—a code Snowden needs to verify himself for asylum applications—and Gellman hesitates. “I just wanna be a goddam journalist,” he texts Poitras; he doesn’t want to be complicit in a possible leak of state secrets to a foreign power. The pressure on him in that moment is unimaginable, but with the benefit of hindsight, his caution seems a form of recklessness. His source’s life was on the line. Gellman admits: “it is clear to me that I misread Snowden badly.”

But his skepticism of Snowden persists even after the documents have been verified. Granted the first interview with Snowden in Moscow, Gellman again takes pains to keep his distance. “I’m not going to suck up to you,” he warns Snowden. “I’m not your advocate. But I’m fundamentally interested in the same debate.” Rather than make Gellman seem more objective, the tough-guy talk—especially so late in the game—only makes Snowden seem more guileless, saintly. That’s the annoying thing about Snowden, from a writer’s perspective: He’s really what he looks like, a man who risked his life to tell us something. To make matters worse, he’s also self-aware and charming, good with words. When Gellman offers to bring him something from the US, Snowden replies in a mock-pitiable tone that he “lives off of ramen and chips, as always. has 400 books (as everyone brings but never has time to read). is an indoor cat, so doesn’t need much.” An indoor cat! Gellman decides on “a few jars of salsa to go with his chips.”

Where Dark Mirror shows the advantage of Gellman’s more methodical approach is in its second half, in particular the section on a program called—and I want credit for having spared you any idiotic NSA code names until this late in the review—MAINWAY. “The vice president’s special program,” is how they knew it inside the agency. It was covered cursorily in the summer of 2013—by Gellman in the Post, by James Risen and Poitras writing together in the New York Times—but gets its deepest treatment here. As Gellman describes it, MAINWAY was an “analytic tool for contact chaining,” in other words a graph that could display “nearly anyone’s movements and communications on a global scale. . . . A database that was preconfigured to map anyone’s life at the touch of a button.” MAINWAY can go back in time, Gellman writes, creating a five-year in-reverse social history. An agent could reassemble a journalist’s source network after a piece comes out. “The government can watch us in retrospect as easily as if it had tracked us in real time,” Gellman writes.

We also meet Ashkan Soltani, an Iranian American ex-hacker turned security consultant who serves as Gellman’s technical adviser on the Post stories. Soltani is the book’s best character after Snowden, because he belongs to the same demimonde as many NSA employees. Where Gellman looks at the Snowden files and thinks of Cheney, Michael Hayden, and former NSA director Keith Alexander, Soltani thinks of DEF CON, Big Gulps, and Emo Cat—signifiers of young male hacker culture. Soltani helps Gellman establish context for the NSA’s paradoxically antiauthoritarian bent: The straitlaced squares at the top depend on the nimble potheads at the bottom.

The bottom is where the humanity is. After the Post stories run, Soltani is catfished on OkCupid by women he knows are too hot for him. “I don’t think I’m a bad-looking guy,” he tells Gellman, “but I’m not the kind of guy women message out of the blue and invite me to cuddle.” The paranoia screws up his dating life. For a long time, he doesn’t leave his phone on the table when he goes to the bathroom. “It’s weird to have opsec when you’re dating,” he says.

Gellman conceived of this book under Obama and finished it under DJT. You can read parts of it as a defense of journalism’s utility at a moment of intense anxiety. It’s a weird time to make that argument. There are a lot of things to expose, but then, nothing happens. Snowden occupies a special perch, because no story in recent memory—with the possible exception of Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey’s Weinstein bombshell—has detonated like his documents. He is the example of journalism working on a global scale.

“I believed in transparency as a leveler of power,” Gellman writes in Dark Mirror, “in the voting booth, the marketplace, and anywhere else decisions had to be made.” This is the assumption that seems most out of sync with reality right now. Do you remember what you read on October 3, 2018? That’s the day the Times released the front-page piece on Trump’s tax scams that also demolished the myth of the self-made billionaire. The reporting is world-class. But if you had to find evidence of an impact, I think you’d struggle.

The same is true of political scandals. Zoë Baird withdrew as the nominee for attorney general in 1993 because reporters found that her nanny wasn’t documented. Last year, the Senate voted to confirm a federal judge who’d never tried a case. What I don’t think was properly anticipated before 2016 was that the government wouldn’t need to suppress information from the public in order to hold power. They would need only to unhook the chain between information-revelation and consequence, either by lying or saying, “So what?” In this atmosphere, revelations of corruption go slack. Information is public but it lacks kinetic force. What makes Snowden exceptional is that his files, like the Weinstein story, had a dual impact: They caused legal and political action while also changing how people think and act. The second impact is rarer and more lasting.

In an early conversation with Verax, Gellman shares an anecdote that reads as a parable. In 1977 he was writing on his high school paper when the principal killed a story about birth control. Aggrieved, Gellman filed a First Amendment lawsuit against her in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. The school district “ran out the clock”—bogged him down in delays—and the principal threatened to write a scarlet-letter note in Gellman’s college file. “The lasting lesson . . . was how easily we were crushed,” he tells Snowden. The lasting lesson of Dark Mirror is that sometimes you aren’t crushed.

Jesse Barron is a journalist based in Los Angeles. He contributes frequently to Bookforum.