“IT WAS HIS QUOTABILITY,” observed the critic Clive James, “that gave Larkin the biggest cultural impact on the British reading public since Auden.” What comes to mind? The opening lines from “Annus Mirabilis,” certainly—“Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three”—but if there is one Philip Larkin quote even better known, it would surely be: “They fuck you up, your mum and dad.”

Did Larkin’s parents fuck him up? According to his sister Catherine (“Kitty”), ten years his senior, both parents “worshipped” Philip. All the same, they have undoubtedly been demonized—sometimes by the poet himself. There were the sour references he made to his childhood in his poetry (“a forgotten boredom”), and then there was his adamantine bachelor’s decision not to marry, seemingly because he did not want to replicate what appears to have been an unhappy parental union. More damning facts have emerged since Larkin died in 1985 at the age of sixty-three, a much-admired and influential figure who had turned down the position of poet laureate a year earlier. These include his father Sydney’s blithe admiration for Nazi Germany, as evidenced by his observing on the first page of his twenty-volume diary (!!) that “those who had visited Germany were much impressed by the good government and order of the country as by the cleanliness and good behavior of the people,” as well as his unrepentant anti-Semitism. As for his mother Eva, Andrew Motion’s 1993 biography of Larkin describes her as “indispensable but infuriating,” like some grating housemaid. Larkin himself characterizes her in a letter to Monica Jones, the longest-running of his several lovers, as “nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying” before going on to amend his portrait: “on the other hand, she’s kind, timid, unselfish, loving.”

So how fucked up, one might go on to ask, was their son? Plenty, some would say. The poet’s shining image as the prototypical provincial Englishman, attached to home and the patches of green that dotted the landscape, was irremediably tarnished when the 2001 publication of Kingsley Amis’s letters revealed his frenemy Larkin to be not just a dedicated “wanker” (although he had admitted as much in his poem “Love Again”) but also something of a misogynist, racist, and general bigot. Anthony Thwaite’s 1992 selection of the poet’s own letters, followed by Motion’s biography (about which Larkin’s older sister declared “there’s no love in it”), also featured the smutty, irascible, and xenophobic sides of Larkin. The critic Tom Paulin led the charge against Larkin’s revered image, declaring that the letters revealed “the sewer under the national monument Larkin became.” And when The Complete Poems, edited by Archie Burnett, appeared in 2012, one reviewer responded to Burnett’s commentary by observing that “the only thing we’re reminded of is what a shit Larkin was in real life.”

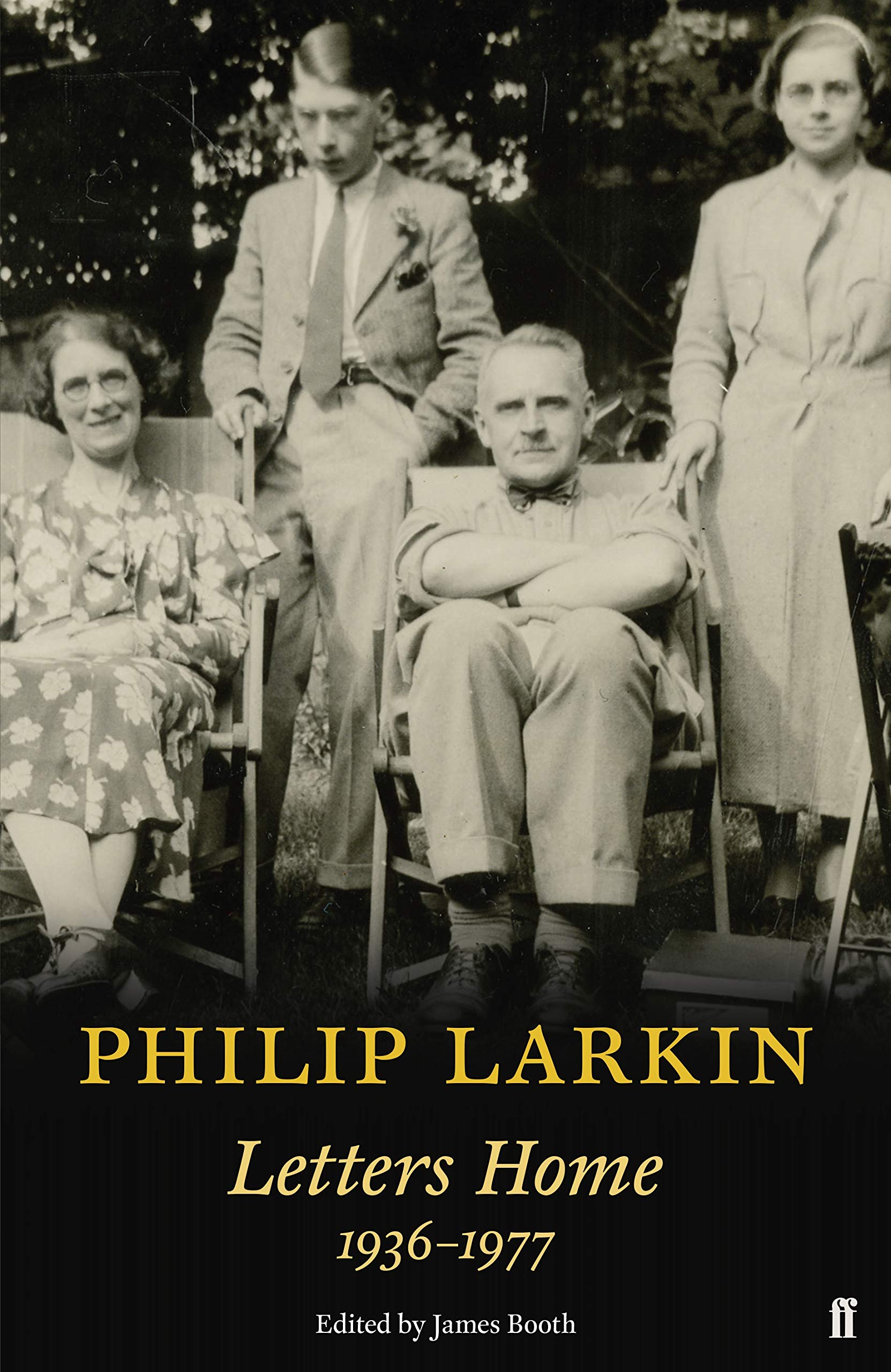

Yet Letters Home, 1936–1977, a recently published fat volume of attentive, touching, and sometimes hilariously banal letters, offers a gently corrective view to all this fucked-upness. They have been ably edited, annotated, and introduced by James Booth, who was for seventeen years a colleague of Larkin’s at the University of Hull, where the poet was chief librarian, eventually overseeing a staff of one hundred. (Booth also published a generous-spirited biography of Larkin in 2014.) Culled from an archive of approximately 4,000 letters, the correspondence selected here contains over five hundred pages of Larkin’s letters and postcards—mostly to his mother (referred to as “Mop” and later as “dear old creature”), with eighty-two of them addressed jointly to both parents (“Dear fambly”), a handful addressed just to his father (“Pop”), and an occasionally testy batch to Kitty.

Sydney, notwithstanding his prejudices, passed on to his son his interest in the history of words and their correct usage in addition to his ecumenical love of reading. Unlike his school friends—who, the poet noted, “were brought up to read Galsworthy and Chesterton as the apex of modern literature”—Larkin found in his father’s library more open-minded choices, such as Hardy, Samuel Butler, Wilde, D. H. Lawrence (both Larkins had a soft spot for Lawrence), and Katherine Mansfield. Sydney also acted with quiet heroism during the blitz on Coventry, where Philip had grown up, and where his parents continued to live until Sydney’s death. His son, meanwhile, wrote to say that over at insular Oxford “we do not know there is a war on.” The worst damage he witnessed seems to be a piece of cracked crockery. “I broke the handle from a tea-cup the other day, unfortunately. This is the first breakage of any sort we have had.”

“To destroy letters,” Larkin wrote his mother, “is repugnant to me—it’s like destroying a bit of life.” (Curiously, this did not stop Monica Jones from destroying thirty volumes of his journals as well as his papers after his death, in the belief that she was acting on Larkin’s wishes.) We learn in the introduction that Larkin almost always wrote in fountain pen and that he liked experimenting with different styles of stationery. “My idea with the orange & red paper,” he writes to Kitty, “was to use orange paper & red envelopes & vice versa. What is your opinion on this?” The letters begin in earnest in 1940, when Larkin is at Oxford, where he sounds for the most part in his element, relatively content and uncharacteristically youthful: “At present I am in a sleepy sea of optimism.” They often include pointillist details about meals eaten (or not eaten): “My breakfast was stone cold yesterday,” he reports to his mother, “& the teapot was half full of leaves this morning”; baths taken; and cautious expenditures, like a “red, yellow & black” tie and an umbrella.

The enormous attention Larkin lavishes on the minute particulars of his existence away from his parents—“I am wearing my red trousers defiantly and daringly”—and his expectation that they will both be breathlessly interested reminded me a bit of Sylvia Plath’s hothouse letters to her mother. Like Plath, he mentions constipation, hay fever (“My nose has snuffles, my throat itches slightly, but as yet I haven’t experienced the real blitzkrieg of sneezing that I usually associate with May and June”), trouble with his teeth, and progress in his writing. And, like her, he is always diffidently asking for care packages of clothes and money. (Although one wonders why Larkin couldn’t buy his own handkerchiefs and underwear—or whether there was perhaps something about the whole infantilizing arrangement that pleased him.)

Similarly, his need to keep up an attitude of good cheer and reassurance when writing to his mother, especially once his “Pop” is gone, put me in mind of Plath’s determination to play the perfect daughter rather than confide the troubled sides of herself to her mother. Still, Larkin is not above exhibiting anxiety and self-doubt: “Oh dear! Oh dear! Oh dear!” he writes home, sharing his conviction that he will be “thirded” on his university exams. “Having gently prepared you for my getting a second, I feel I shall have to prepare you for a third or lower.” Needless to say, Philip goes on to graduate with a first-class degree in English in July of 1943, which triumphant news he telegraphs home.

THE BACKBONE OF LETTERS HOME consists of the missives Larkin wrote to his mother Eva every Sunday over nearly thirty years, sometimes with an additional letter or card during the week; they describe socks he was mending, laundry he was about to attend to, and a pair of scissors he was considering buying. They begin in 1950 (Sydney died in 1948), after he had lived with his mother for two years and moved out to take a post as a sub-librarian in Queen’s University Belfast; many of them include charming drawings by Larkin and cartoons he thought his mother might like. (Booth has also provided some of Eva’s responses in footnotes and in an Appendix.)

“Irritating” or “infuriating” as he thought she was, Eva seems to have been a burden and a cheerleader at once—a mollusk who clung to Larkin, was afraid of thunderstorms and being alone, but also was a supportive and admiring parent, a perceptive reader of her son’s poetry, and surprisingly unintrusive (she never inquired into his romantic arrangements, opaque as they seemed). They shared recipes and menus as well as a depressive temperament, although Larkin was more adjusted to his habit of seeing the dark side of things—“I have a premonition of dreary dullness, of nasty people, nasty living conditions”—and more capable of appreciating the sunnier vistas when they appeared: “For once again the day is fine,” he wrote his “dear Mop-Creature” in May of 1952, “expansively fine, deliciously fine, splendidly fine.” In one letter he even admitted that, after taking a walk in the meadows around Christ Church during a June 1955 visit to Oxford, “I felt really glad to be alive. How I love summer. . . . Gorgeous rich expansion of everything!”

His mother, on the other hand, was persistently anxious and just this side of distraught, despite Larkin’s efforts to remind her that there was a larger world out there than her “prison of misery” would allow for: “But, dear old creature,” he wrote her in May of 1953, “there are more things in life than thunderstorms—trees, stars, rivers, all costing nothing to look at. It takes quite a bit to crush any human spirit, so take courage! Now I must go to bed.” This is not to suggest that there was an excess of merriment in Larkin’s character, but that he had his pleasures, no matter how he set out to disparage them: his writing and his work, his indecisive yet heartfelt romances, and his active social life (of which there was more than one might have expected from a poet who embraced solitude as one of his primary themes).

Eva, by contrast, had fewer inner resources or outside distractions; except for a scattering of domestic chores she had little to occupy her time and, save for visits to her daughter and son-in-law, she was very much alone. In the summer of 1955 Eva’s doctor referred her to a psychiatrist (Larkin wrote to her, “So you are going to see a psychiatrist! It’s very bold of you”), who prescribed “tablets”; later that year she was diagnosed with clinical depression and received electric-shock treatment. The same day she had ECT she wrote to her son, despite feeling “a bit shaky and sick,” that “I feel very proud to know that you are now recognized as a foremost English poet.” Under the circumstances this seems like a particularly moving and selfless sentiment.

I FIRST READ LARKIN IN A COLLEGE CLASS on contemporary poetry. “Deceptions” was from Larkin’s second volume, The Less Deceived, and was included in an anthology edited by M. L. Rosenthal called The New Modern Poetry: British and American Poetry Since World War II. I had always fashioned myself a poetry buff and had started writing poetry in my youth, some of it good enough to eventually win something called the Amy Loveman Memorial Prize “for the best original poem by a Barnard College undergraduate.”

By the time I was introduced to Larkin I had read a lot of Yeats, Williams, and Auden, as well as the Metaphysical and Romantic poets, but nothing had prepared me for his singularity: the use of the vernacular, the imagery, the immediacy, the compression, the lyricism, and, perhaps most of all, the unexpected note of empathy. How could a male poet writing in the 1950s identify so fully with a Victorian servant-girl who had been raped? “Deceptions” boggled my imagination then and continues to do so now whenever I reread the poem. Then there is the cascade of original phrasing, the unexpected metaphors (“the grief, / Bitter and sharp with stalks” or “the brief brisk / Worry of wheels”) and the sublime similes: “Your mind lay open like a drawer of knives.” I think it was this latter image—the leap of imagination that got at the vulnerability of the girl, her violated sense of self—that converted me on the spot to an avid and enduring Larkin fan. At a secret dinner party hosted by historian Hugh Thomas in 1982, Margaret Thatcher, whom Larkin was close to besotted with, quoted—or misquoted, depending on which account you believe—this very line to him.

In the ensuing decades I have remained passionate about Larkin. I read his two intriguing if not entirely successful novels, Jill (1946) and A Girl in Winter (1947), early on, then continued to pore over the rest of his slim output of poetry, his jazz reviews and literary pieces, the biographies, the letters, the memoirs about him, all of it. At Columbia graduate school, before Larkin had become well-known on these shores (this was the late 1970s), I was told by my English professor that I was too “young” to like so dour and misanthropic a poet. Undeterred, I started a master’s thesis on the influence of Thomas Hardy on Larkin; I did massive research, as was my way, and still have the narrow-lined notebook in which I took recondite notes, but I never finished the thesis (as was also my way).

Nowadays, I have a favorite poem over my desk (“Days”) to remind myself that sometimes the search for inherent meaning—“What are days for?”—ends in a bustle of imminent explication rather than an immediate, clear-eyed answer: “Ah, solving that question / Brings the priest and the doctor / In their long coats / Running over the fields.” I also have in my possession a double CD called The Sunday Sessions, on which Larkin reads twenty-six of his poems in a self-conscious, slightly strangled voice. And, to top it off, I once went so far as to write him a letter c/o the University of Hull to ask if I could visit him were I to be in the neighborhood (unlikely a possibility as that may have been) and remember receiving a terse but polite reply that managed not to say “no” while not actually saying “yes.” I think I imagined sailing in and coaxing him past his habitual diffidence—into what, I’m not sure, but the point was to meet the man in all his bespectacled and pasty non-splendiferousness.

I’M NOT SURE, EITHER, WHY THESE LETTERS, in all their repetitive prosaic detail, are as fascinating as they are, but perhaps it is their very prosaicness that makes them compulsively readable. Rather than being filled with “windy philosophical tosh about mankind” or patronizing intellectual asides (other than correcting Eva’s occasional misspellings), Larkin’s letters are steeped in the quotidian. He was a man, after all, who could quote Goethe’s purported last words in the original German (“mehr licht”) and who hobnobbed with such literary personages as E. M. Forster (“He was very pleasant, but I found it hard going to talk to him”), Stephen Spender (“Stephen Spender called in on Friday & talked about his father & Lloyd George for the best part of an hour”), “an aged but spry” T. S. Eliot, and “an incredibly small and tousled, grubby Welshman” named Dylan Thomas. Yet he preferred to regale his mother with the specifics of meals eaten (“Trinity College was very interesting. The dinner was: celery soup, Lobster Newburg, pheasant, & apple pie with real cream”), his daily routine (“Yesterday too I bought another cabbage. I find a good deal depends on one’s cabbage of the moment. Last week’s was tough & I am chucking away about half of it. This new one is much more tender”), and the unsingular minutiae of his life as he was living it. “It’s another very fine Sunday morning here,” Larkin reported in November 1950 from Belfast, “quite warm, and people are strolling up and down the road outside. Have two open windows and have just opened a third but I fancy I shall close that one. Moderation in all things!”

Once in a while, in passing, he offers an image—“a lilt of slightly cracked Irish laughter,” “the sky was like one enormous bruise”—that reminds us of the heights he was capable of ascending to in-between bemoaning his growing paunch and the household tasks that await him (“Well, I must do a little tidying and shoe-cleaning”). Inevitably, because Larkin is Larkin, the letters also contain glimpses of his self-deprecating humor—“I tried to look grave,” he writes about an official photo taken of him, “kindly yet humorous withal, but shall doubtless emerge as the popeyed small mouthed fat-cheeked balding gold-rimmed version of Heinrich Himmler we all know so well.” And then there’s his accrued wisdom, his insights into the entrapments of the material world, all conveyed with a disenchanted, clear eye: “Money should be like a skin,” he tells his mother, who worries needlessly about expenditures (she was left a well-off widow), “something one’s not aware of unless it goes wrong.”

I suppose there are those who would argue that these letters are no more than occasionally amusing ephemera, dutifully composed to make an old and needy woman happy, which contribute little to the already complicated picture of Larkin that we have. I would argue otherwise. For one thing, Larkin truly took pleasure in writing them and receiving Eva’s replies in return: “I love to hear the little details of your life,” he wrote her on November 28, 1956, before going on to announce his plans to “take things to the cleaners & buy some bacon.”

For another, they reveal sides of Larkin that were too often submerged under his occasionally puerile letters to his male correspondents and the detached and dolorous persona of his poems, the persona that issued such woeful pronouncements as “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were for Wordsworth.” We know that side of Larkin best; it is what provides his poems with their startling, unblinking clarity and their inimitable mixture of rigor and pathos. It is, as well, what gives the poet his stature as a truth-teller, someone who refuses to be consoled by pieties or bromides. Larkin’s letters to his mother, however, throw light on his deeply human capacities to connect and empathize, not just to observe and ridicule. Eva, in all her tremulous dependency and her constant requests for assurance, might have been easily seen as an object of fun, a drain on her son’s nerves, but instead Larkin, except for a few occasions when he grew frustrated and annoyed (after which he apologized profusely), treated his mother with utmost tenderness and respect, taking her small, obsessive woes seriously and commiserating when things went wrong. In some way it was Eva’s life, rather than the lives of his lovers, that captured and captivated him, leaving him unavailable to commit to other domestic arrangements.

There remains the question: Was Eva really his “muse,” as James Booth suggests in his introduction, grounding him in the material of the mundane and the ordinary, the better that he might transform and set wing to it? “She is a muse,” Booth argues, “in the time-honored sense of being beyond the poet’s reach. Poetry is made of her, but she herself is unconscious of it.” This is certainly worth considering, especially given the fact that Larkin finished “Aubade,” his great poem about the pitiless, ungraspable inevitability of our own mortality—“Not to be here, / Not to be anywhere, / And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true”—just days after Eva died on November 17, 1977, and wrote very little after it. Perhaps, curious as it may seem, this inhibited and introverted man (he had a lifelong stammer) could write for the larger world he kept mostly at bay only by accessing the cozy, humdrum world he saw through his mother’s eyes; despite her own fragility, it was she who centered and helped define him. It would explain the unique approachability of his poems, the way many of them tell a story rather than trying for a fireworks of unreferenced imagery, imparting meaning to an everyday reality with the lightest of touches.

Letters Home is a close look at a time that seems strangely long ago in its insularity—the outer world seems to impinge almost not at all—and into a relationship that speaks to and reinforces a theme of Larkin’s that frequently gets overlooked amid the malaise and acute ambivalence that mark so many of his poems. “What will survive of us is love” (“An Arundel Tomb”). Coming from someone else, someone more given to easy sentiment, the phrase could sound like a truism—or a misty statement at the end of a priest’s sermon. Coming from Larkin, it seems hard-won and inspiring, not a denial of the eternal darkness that awaits us but a reminder of the affection that girds us one to the other while we’re here.

Daphne Merkin is a cultural critic and memoirist. Her novel 22 Minutes of Unconditional Love was just published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Her first novel, Enchantment (1986), has just been reissued by Picador.