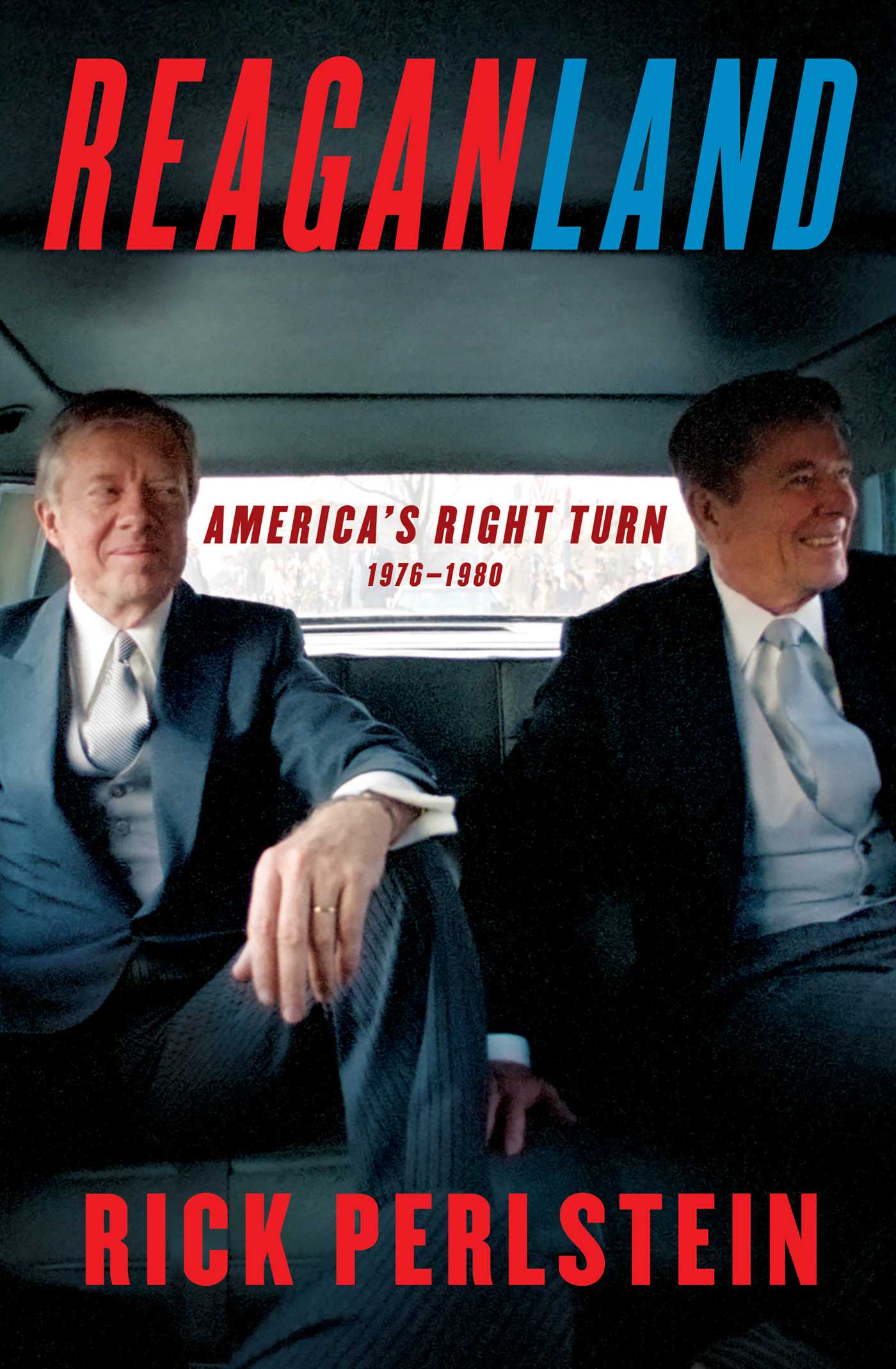

THEY’RE BOTH ON THE BOOK’S COVER, in the backseat of a limo, winner and loser of the 1980 presidential sweepstakes, riding, one presumes, to the inauguration of the one on the (so to speak) right. The outgoing president, giving the side-eye to his successor, stoically bears what one might view as an enigmatic half-smile. When things were going better for him four years earlier, his full-bore eighty-watt grin was his calling card, his ticket to glory. He’ll smile like that again someday, but it’ll never be the same. The incoming president? Nothing can harsh this guy’s mellow on this bright-and-frosty “morning in America,” as television ads later named the historic moment . . .

We are more than forty years removed from the events chronicled in Rick Perlstein’s Reaganland—and, as I write this, less than three months away from another presidential election that promises to be as transformative as the Reagan-Carter showdown. Of course, people say that about every presidential election, especially the candidates who are running for office. But 2020 has already proved transformative enough, as the volatile COVID-19 pandemic threatens lives, forces millions into isolation, immobilizes worldwide markets, and possibly sets the stage for our president to dispute election results if they do not go in his favor.

The arrival of Reaganland—the fourth and final volume of Perlstein’s enthralling history of American political conservatism’s resurgence in the mid-to-late-twentieth century—offers readers the opportunity to comb through its 1,100-plus pages for omens, precedents, or at the very least faint clues that point to how in bloody hell this conservative wave culminated in the improbable, unfathomable, and all-but-calamitous presidency of Donald J. Trump. Which is no simple task, not even when the incumbent president shows up among the thousands of bit players passing through Perlstein’s immensely detailed saga. Here, we meet Trump in 1979, when he is little more than a roguish real-estate tyro, a “hungry young killer” conspicuously on the make in his native New York City.

You can also find a portentous indicator of the nation’s political trends in the long-ago deeds of Trump’s 2020 adversary. As Perlstein recounts, Joseph Biden had first reached the senate in 1972 at age twenty-nine as a doctrinaire Democratic liberal, but afterward had “become the senator from outside the deep South who did the most to stymie busing to achieve school desegregation, and pioneered the imposition of mandatory sentences for federal crimes.” These and other rightward shifts in Biden’s voting pattern helped the junior senator from Delaware “glide” to reelection in 1978, the same year that Proposition 13, California’s tax-lowering, budget-slashing initiative, was endorsed by 65 percent of the state’s voters, many of whom “stood to be directly harmed” by the results. “It was,” Perlstein writes, “a rout.” Democrats like Biden, it now seems, could survive in office only by negotiating safe passage through the mounting wave of conservative indignation against excessive “government intervention.”

And there was, you may recall, a Democrat in the White House at that time named Jimmy Carter. For all his efforts to bring more compassion and honesty to government in the aftermath of Watergate and Vietnam, Carter was just as skeptical as his GOP opponents of the notion that government could, or should, solve everybody’s problems. The difference was that Carter tended to express such skepticism, as Perlstein writes, “in the manner of a wartime president,” acknowledging hardship while calling for sacrifice and discipline in the face of the energy shortages and economic stagflation that dominated his ill-starred administration. The engineer-farmer-Baptist from Plains, Georgia, made it his mission to call on ordinary citizens to lower their thermostats to save energy, and to urge members of Congress to give up some of their perks—along with some of the ambitious river-damming projects in their states. Upon meeting with Carter about such projects in his home state of Nevada, Republican senator Paul Laxalt was moved to inform his good friend and California neighbor Ronald Reagan, “My gut tells me that I’ve just met with a one-termer.”

Among the few high points for Carter in those years, besides his hard-won victories in securing a seamless transfer of power over the Panama Canal in 1977 and in midwifing a historic peace accord between Israel and Egypt in 1978, was his 1979 television address about the “crisis in confidence” threatening to “destroy the social and the political fabric of America.” It was one of the more incisive, candid, and inspiring addresses in presidential history (it is remembered as Carter’s “malaise” speech—a somewhat imprecise and unfortunate label, not least because that word is not used once). As Perlstein recounts, the speech gave the president “an eleven-point bump” in approval ratings. But as was the dismal pattern throughout the Carter presidency, the triumph was quickly overwhelmed, in this case by the administration’s abrupt and massive personnel shake-up. This may have been little more in retrospect than Carter trying to add a “clean slate” sheen to his administration to go with the fresh resolve he urged in his speech. But to the political media of the era (and to Carter’s opponents), the optics were reminiscent of Richard Nixon’s notorious “Saturday Night Massacre” six years earlier in the thick of the Watergate cover-up. “It went from sugar to shit right there,” recalled Vice President Walter Mondale.

In the end, it probably didn’t matter that Carter talked sense to the American people, because what’s clear from reading Reaganland is that the American people weren’t in the mood to be leveled with. They wanted to hear what made them feel better. Enter Ronald Reagan with his sunny riffs on how the country’s best days were still to come—all the government had to do was step aside and let free markets do what they do best: stimulate growth and keep America strong. It wasn’t always clear—and it still isn’t when reading these riffs in Reaganland—how exactly all that was supposed to happen. But who cared? Hardship, smardship! USA All the Way!

Such stark contrasts between Carter and Reagan make the latter’s triumph retroactively seem as inevitable as daylight. But if you’ve been riding along with Perlstein since 2001’s Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus, you will remember that at the end of his third and most recent volume, 2014’s The Invisible Bridge, the “former California governor,” as Reagan was mostly labeled in the immediate aftermath of Watergate, failed to win his scorched-earth challenge to then-president Gerald Ford for the 1976 Republican nomination. Though Reagan came away looking more victor than vanquished (and appearances meant a great deal to this product of Hollywood), his loss at the buzzer convinced pundits and other custodians of conventional wisdom that he’d had his last shot in ’76. Because he was by then already “sixty-five years of age,” the New York Times opined, he was “too old to seriously consider another run at the Presidency.”

Indeed, the news media’s oracles insisted Reagan couldn’t win in 1980, no matter how far ahead he was in Republican polls. As Perlstein writes, “Any utterance too far out in right field, any wire-service photo of him falling asleep at some interminable Republican banquet, would be all it would take to finish him.” Practically till he moved into the White House, Reagan was generally regarded as a “fringe” right-winger who shot from the hip, seemingly at random. He continued to defend Nixon for his Watergate excesses well after the thirty-seventh president had become a non-person, even within the GOP. You’d have thought everybody in America at that time loved Roots, the landmark 1977 TV miniseries adapted from Alex Haley’s best-selling account of an African American family during slavery and beyond. Not Ronald Reagan: “I thought the bias of all the good people being one color and all the bad people being another was rather destructive.” You’d have thought in the aftermath of the 1979 near-catastrophic accident at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear facility that every American would be shaken to the core. Not Ronald Reagan: “No one was killed, no one was injured, and there will not be a single additional death from cancer among the two million people living within a fifty-mile radius of the plant.” Reagan had been issuing caustic, reactionary, and unpredictable opinions as far back as his late-’60s-early-’70s gubernatorial tenure—during which he offset a government hiring freeze by increasing state spending by 9 percent and, with unwanted help from gun-toting Black Panthers in the state capital, signed a law prohibiting open-carry of firearms.

Reagan was, in fact, considered an extreme risk when he announced his presidential bid in 1979. Some GOP pols opted to put their chips on John Connally, a conservative Democratic Texas governor turned conservative Republican treasury secretary, who was a strutting-peacock favorite of what Perlstein characterizes as “boardroom Jacobins,” corporate leaders and lobbyists in pitched battle against the specter of government regulation. No less a Democratic icon than Arthur Schlesinger Jr., historian and courtier to the Kennedys, opined that Connally’s “charisma and its effect” made him a shoo-in for the nomination. As we now know, Connally’s campaign foundered the following March after he was trounced by Reagan in the South Carolina primary.

Reaganland detonates revelatory pop-ups like this throughout its narrative. Taken together, they illuminate an era that remains a dreary, hectic blur to those who lived through it. As with the best popular histories (an undervalued subgenre, even with such widely acknowledged masters of the form as Barbara Tuchman and William Manchester), Perlstein’s book not only rolls out its sequence of events but also evokes their emotional impact, whether it was shock, incredulity, or delight. No dots go unconnected in his American tableaux, in which the popularity of movies like 1977’s Star Wars and 1978’s Superman contribute as much to the country’s enchantment with rousing triumphalism as the US hockey team’s “Miracle on Ice” upset over the USSR in the 1980 Winter Olympics.

Nothing seems left out: Son of Sam, Jonestown, SALT II, the counter-feminist revolt against the Equal Rights Amendment, the murders of San Francisco’s liberal mayor George Moscone and gay city supervisor Harvey Milk, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and, inevitably, the events leading up to and including the seizure of the US Embassy in revolutionary Iran. Few remember that Carter was initially reluctant to carry out the fateful decision to let the deposed and dying Shah of Iran into the US, which incited the takeover of the American embassy in Tehran. (“Fuck the shah!” Carter snapped before finding out the extent of the ex-monarch’s illness. “He’s just as well playing tennis in Acapulco as he is in California.”) But many do remember the 1979 “killer rabbit attack” against the president while he was fishing near his hometown of Plains. This “funny little story” metastasized into a multicourse meal tabloids and TV dined on for months, as opponents offered unwanted advice: GOP senator Bob Dole thought Carter should apologize to the hissing, teeth-baring bunny, while Moral Majority leader Jerry Falwell said Carter should have slayed the beast as a hedge against the book of Revelation’s apocalyptic prophesies.

Poor Jimmy. But what chance did an earnest fellow such as he have back then against one of the most ruthlessly effective coalition builders in political history? The left-wing activist in Perlstein has from the first volume of his tetralogy displayed a rueful (likely envious) appreciation for right-wing activists’ focus on fulfilling their ultimate goals between 1964 and 1980. He respects the shrewdness of what would be labeled the “New Right” as it staked its future on playing an “inside” game of consolidating conservative Republicans’ influence in Congress (despite a Democratic majority in both houses) and an even more effective “outside” game of channeling the resentments of white middle- and upper-class taxpayers who thought government subsidized social change had gone too far. The new coalition brought together the aforementioned “boardroom Jacobins”; apostate liberals who were massing together around something labeled “neoconservatism”; and religious fundamentalists alarmed enough by the specter of gay and women’s liberation and what they perceived as the nation’s drift away from “family values.” They all attached their hopes and dreams to a candidate who had mastered the illustrative anecdote, no matter how dubious its content (e.g., his widely discredited “welfare queens” whopper, which rarely failed to get a rise out of aggrieved white voters). What’s more, Reagan gave them the opportunity to recast their own self-interest as noble causes. As Perlstein puts it, Reagan possessed the “ability to effortlessly package the quest for corporate profit into an uplifting vision of a righteous citizens’ crusade.”

For conservatism to hit its stride, however, liberalism had to lose its footing. During the ’70s, the Democratic Party continued to press for affirmative action, federally subsidized housing, corporate regulation, and other issues buttressing its core values. But as Perlstein notes, the Federal Election Campaign Act Amendments of 1974 made it easier for corporate lobbyists to form political action committees, and “under this money onslaught, the ideology of Democratic members of Congress shifted right—or rather shifted further right.” Jerry Brown, Reagan’s dryly inscrutable Democratic successor as California governor, was most prominent among the party’s rising stars to take up Carter’s call for greater sacrifice in the face of limited resources. But Democrats old and new had to deal with the middle class’s increasing resistance to giving federal aid to the poor. A legacy of the Carter-Reagan years has been a general reluctance by most politicians of either party to utter the word “poverty,” as if the condition itself were a myth left over from Lyndon Johnson’s ’60s vision of a “Great Society.”

Democrats who still cherished unadulterated party values shifted their allegiance from Jimmy Carter to Massachusetts senator Edward Kennedy, whose dogged challenge to the president in the 1980 primaries was further evidence of the incumbent’s weakening prospects for reelection. Yet it’s telling that in a major CBS News profile of Kennedy, which aired just days before his November 1979 official announcement of his candidacy, the senior senator from Massachusetts was mostly tongue-tied, stammering and at a loss for words, most notably in response to interviewer Roger Mudd’s softball question as to why he wanted to be president. Kennedy won enough primaries the following spring to stay in pursuit until that summer’s Democratic National Convention, but the interview became as much of a burden on the candidate as the Chappaquiddick tragedy a decade before. In a way, Kennedy’s fumbling was emblematic of the liberal faith losing its voice just as conservatism’s was finally being heard.

Though Kennedy was able to recover the Democratic voice long enough at the convention to deliver a rousing and eloquent defense of the party’s dwindling vision, it was already too late—or so it now seems. The dimensions of Reagan’s landslide and the concurrent fall of the Democratic majority in Congress came as a surprise to reporters and pollsters, many of whom had Carter and Reagan neck and neck up until the weekend before Election Day. In the days and months that followed, there were some observers (not Perlstein) who believed that Reagan had somehow performed a magician’s hypnosis upon the electorate that made it forget the extreme statements and positions with which he was long associated. I did not then and do not now buy this explanation, and Perlstein’s chronicle, which seems to be in something of a hurry to conclude, makes me even more certain that, in the end, the people who voted for Ronald Reagan and his politics in 1980 knew exactly what they were getting—and, as suggested above, they did not care. (Hardship, smardship!)

And this year? The ongoing threat of the pandemic has among many other things made Americans aware of the wide disparities in medical treatment available to the economically challenged. Concurrently, the death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black Minneapolis man, while in police custody has jump-started demonstrations throughout the country in which people of many ages, races, and religious backgrounds are protesting excessive police force while confronting, to an unprecedented degree, systemic racism. The erstwhile “hungry young killer” has aged into a bloated, bigoted crank, whose election to the presidency four years ago is allegedly being viewed by some who punched his ticket back then with “buyer’s remorse.” Does Joe Biden now carry similar remorse for the positions he adopted in the late ’70s? Is there a reckoning coming as decisive as the “morning in America” of forty years ago? I’m not sure any lesson from the past can be taken as altogether reliable in this most extraordinary of calendar years. Still, the unlikely changes in the American electorate that began with Barry Goldwater’s doomed 1964 campaign tempt one to coin a phrase that Yogi Berra never said but should have, so it could be branded inside pollsters’ foreheads: nobody knows nothing about anything—until it happens.

Gene Seymour is a writer living in Philadelphia.