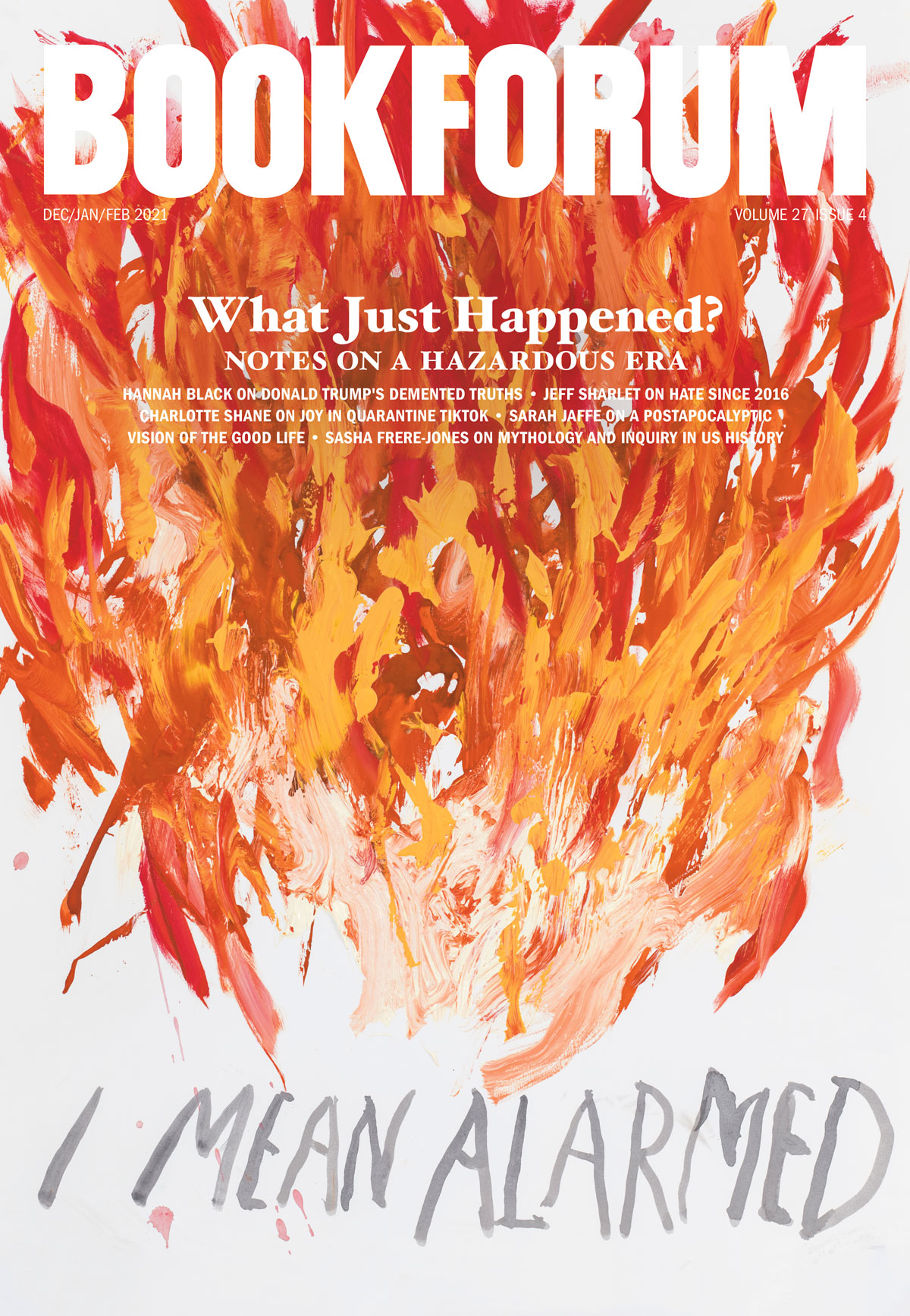

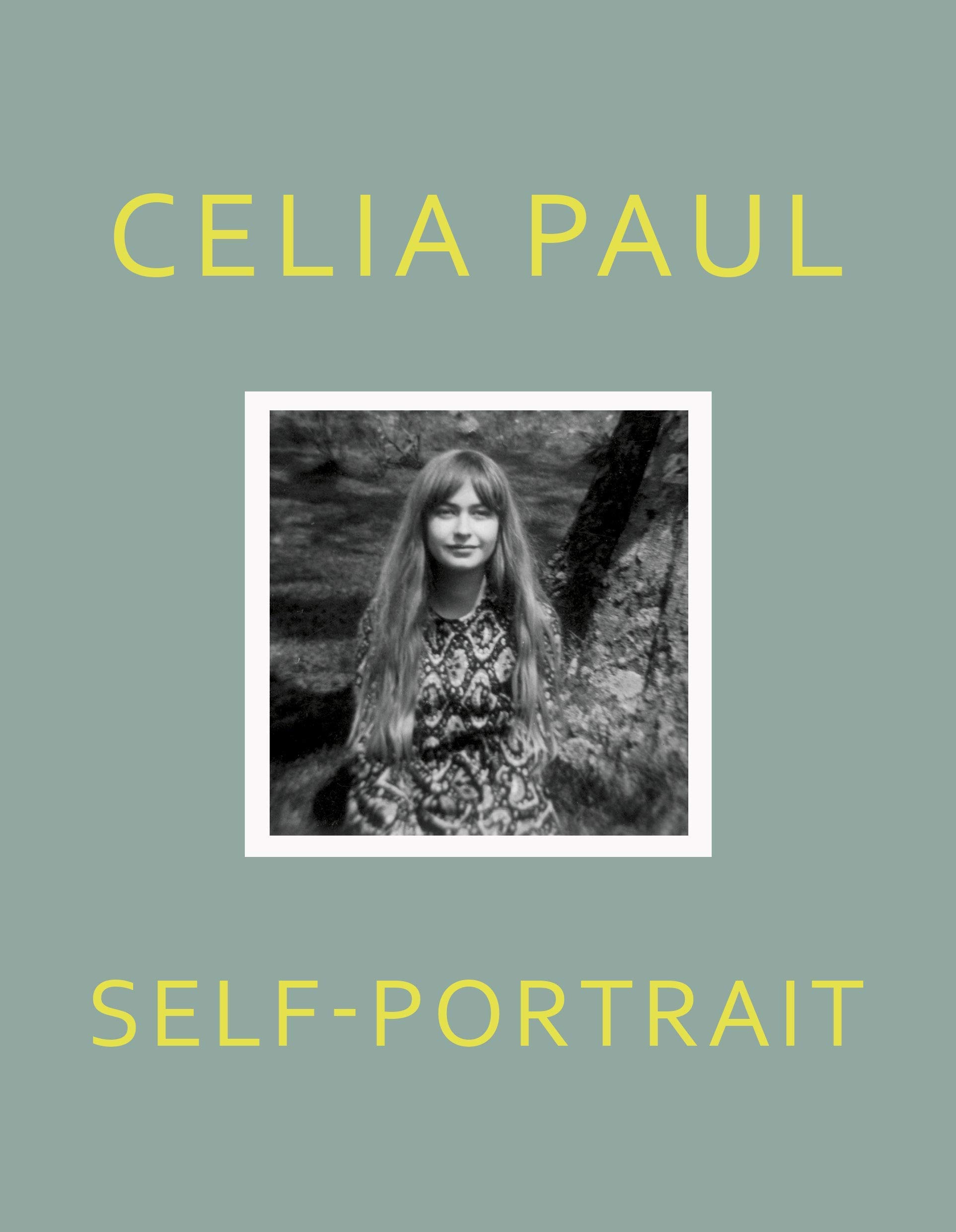

A FRIEND OF MINE dating a famous artist jokes that she dreads her obituary reading that she, in addition to having been the girlfriend, was “accomplished in her own right.” In her own right! The mind heaves. Anyone who has been romantically involved with a famous artist knows the risk of being overshadowed. For those who nurture artistic ambitions themselves, the challenge is twofold: to avoid being subsumed by their partner’s success and to insist upon the importance of their own work. Self-Portrait, Celia Paul’s memoir and account of her decade-long entanglement with Lucian Freud, is both the story of a life and an argument for her own legacy. To be known as Freud’s companion might be fine, for a time; to be canonized as such would be unbearable. His death in 2011, and her subsequent subordination as Freud’s lover and muse, made it seem unlikely that she would ever be known simply as “the painter Celia Paul.” But Paul’s memoir is more than an attempt to balance the scales. Self-Portrait is the work of someone who has learned how to see herself.

Celia Paul was born in Kerala, India, and raised in Lee Abbey, a religious community in England; her father was a pastor and theologian, and the family followed wherever his vocation took him. Growing up devout breeds a peculiar disposition, marked by a penchant for grandeur and the tendency to forgive another’s outsize ego, traits that could be seen in retrospect as symptoms. The fourth of five daughters, Paul remembers her small self as a graceful, astute observer (“As a child in India, . . . I sat so still in the beautiful garden of our house in Trivandrum that the butterflies landed on me”) who was given free rein to look and draw obsessively. But a dreamy imagination is not always benevolent. When her youngest sister, Kate, is born, Paul, traumatized at the thought of being displaced in her mother’s affection, “resolved to die.” She falls ill and is diagnosed with leukemia, the impetus for the family’s return to England, where, following a treatment at Hammersmith Hospital, she is “pronounced cured.” Her parents talk about a miracle, prayer’s victory. Paul uses the heathen synonym “success.” It is jealousy that triumphs: “My mother gave me her devotion for the rest of her life.”

Devotion levies a tax on privacy, and from the time of her recovery the young Paul is rarely left alone. She is sent to boarding school in Bideford, and during her weekends at home, the family shares their meals with the parishioners. As a means of escape, Paul arranges bits of life from the Exmoor coast—“driftwood, a crow’s wing, a wasps’ nest, bits of rusted machinery”—into makeshift still lifes. Painting, she writes, is a way of “guarding and controlling my inner life.” Boarding school, that cave of psychosexual obsession, seals her fate. There, Paul is drawn into an intense friendship with her classmate Linda Brandon, who wears her dark-blonde hair in thick bunches and whose pinched smile gives her “a diffident air.” The girls lie down in a field of buttercups. They write poetry, make detailed drawings of plants and flowers. As with Fleur Jaeggy’s Frédérique in Sweet Days of Discipline, Paul’s relationship with Linda is hastened by awe and heightened by a “powerful undercurrent” of competition, which begins to flow at the sight of her friend’s drawings and paintings. Paul forgets her ambivalence about art as a pursuit, and starts painting in earnest, trading nights with Linda in the school studio until the winter break, when Paul returns with a slew of work and Linda with nothing. Again, her success has the faint scent of ash. Linda mistrusts her; it’s mutual. Their art teacher secures Paul a meeting at the famed Slade School of Fine Art in London, where she is granted early admission. “Pictures unpainted make the heart sick,” Slade professor Sir Lawrence Gowing pleads in a letter to her reluctant father.

Paul’s first encounter with Lucian Freud, in the basement studio of the Slade in 1978, has the lurid quality of a paperback gothic romance. Wearing a “tailored grey wool suit” with a white silk scarf, smoking a Gitane, Freud, who “only came to the Slade to pick up a girl,” stares at the naked model lying on a filthy mattress. Paul, one of the students sketching, stares at Freud:

His face was very white, with the texture of wax. It had an eerie glow as if it was lit from within, like a candle inside a turnip. His gestures were camp. He stood with one leg bent and his toes, in their expensive shoes, were pointed outwards. He sucked in his cheeks in a self-conscious way and opened his eyes wide until I looked at him, and then his pupils, which were hard points in his pale lizard-green irises, slid under his eyelids and I could only see the whites of his eyes.

One moment Paul is showing him her work, the next he’s hailing a taxi to his flat, under the auspices, of course, of showing her his own. “As we drove west,” she recalls without embarrassment, “the low autumn sun was blinding. He took my hair and wound it around his fingers and started stroking my throat with a soft rotating movement. I felt his knuckles on my throat through my hair.” Freud tells her she looks “so sad,” a supposition she seems not to deny. He gets her phone number. On their second meeting, he says that she reminds him of the Virgin in Michelangelo’s Pietà, which is to say that they soon become lovers. Paul stops brushing her hair, wears unwashed clothes. The disturbance of sex echoes at a medieval depth. “I felt that I had sinned and that something had been irreparably lost. . . . I felt that I had stepped into a limitless and dangerous world.” She is eighteen years old; he’s fifty-five.

Paul is in a state of constant anticipation. She spends ages waiting by the phone (“Lucian hadn’t given me his phone number, so I often spent days in my room, too afraid to go out in case I missed his call”), consumed by shame, obsession, and depressive thoughts. A Cheshire cat disguised as a man, Freud slinks between her and others, outdoing her in secrecy, in envy. She swallows a packet of Veganin with whiskey. Perhaps belatedly, she fears going mad. Yet throughout it all—the fear as well as the drama—she paints to maintain self-respect and repeats, as the affair bears down on her, mantras of ambition and desperation: “I don’t care so much what the outcome of the painting is so long as I finish it.”

In the autumn of 1980, Freud asks her to sit for him, the first of many such sessions. Stripped, drawn into “uncharacteristic” positions, she feels “disarmed,” deadened, “like I was at the doctor’s, or in hospital, or in the morgue. . . . I cried throughout these sessions.” The paintings that come out of this period serve as an embodiment of the psychological state of their relationship: Freud peers down, and Paul appears locked in a private, frantic world.

Intimacy with Freud’s impatient genius leads Paul to adopt a similar artistic persona. Returning home for the holidays, and determined to complete a major painting, she strong-arms her mother into sitting for her, instructing her to take off her clothes and guiding her into particular poses. “When [my mother] faltered and didn’t get the position just as I had wanted, I shouted at her. I was very cruel. She cried and said that I was treating her like an object. I responded irritably to her tears and said that she didn’t believe in me. She complied and continued to pose for me, day after day during the holidays.”

Over time, Paul’s youthful aggression shifts focus: her relationship with her models becomes more symbiotic and her paintings become more psychologically taut. Her mother, who would continue to be her main subject until her death, acquires a sense of peace and pride sitting for her. Paul works from people and places she knows well, and the intimacy of time accrued lends her figures their mysterious stillness. The grace of her paintings—in which the interiority of her subjects is simultaneously depicted and protected—is echoed in her prose, which is pared down and elegant. In her writing, the act of remembering is as simple as walking from room to room. Her descriptions of paintings are crystalline: an unnamed Delacroix holds “tiny points of luminous turquoise paint that seem to grow from the canvas as unpredictably as bluebells in a wood”; Rembrandt’s Polish Rider, in which “the head of the rider is placed in vertical relation to the pyramid of the mountain,” is a “sheltering edifice.”

In 1984, Paul gives birth to a child, Frank, and Freud’s hold over her begins to dissipate in the face of her “powerful tide of maternal love” for their son. She briefly takes up with a younger man, but it’s clear her interest in romantic peril has dwindled. Not one to be outdone, Freud quickly becomes seriously involved with another woman, and the two grow apart. In 1988, when Paul officially concludes their relationship, she has already moved into a flat across from the British Museum purchased for her by Freud and become increasingly hermetic. It is clear she will paint until she cannot.

Were Celia Paul and Lucian Freud not great artists, the story of their affair might read as a cliché. Young girl from the backwoods with an outward naïveté that belies an iron will meets an older, theatrically unattractive, cultured man. The girl, who doesn’t distinguish between love and subjugation, falls for him. He needs adoration; she conceals her own needs. Years of emotional torment follow. Gradually, she begins to assert her ambition. Maybe she leaves him; maybe she becomes the subject of her own life. This might be called a success, but Paul doesn’t insist on our seeing it that way: in Self-Portrait no one is that innocent, and no one escapes unscarred.

Janique Vigier is a writer from Winnipeg.