I REMEMBER BETTER THAN MOST where I was when I knew Donald Trump would win. Not just that he would win but that “the office” would not subdue him, that he was coming because he was the crest of a wave, a force made unstoppable by its mostly unseen mass. It was October 9, 2016, I was forty-four, and I was having a heart attack. On the TV above my hospital bed, at his second debate with Hillary Clinton, Trump loomed over Clinton’s shoulder. My nurse, a Trump supporter, gave me a drip of nitroglycerin. It was a slow-moving heart attack. It’d gathered strength across days, at first fooling the ER doctors, who’d told me tests made them “95 percent certain” my heart was fine, which happens to be about the same certainty with which most pundits spoke of the imminent Clinton victory. The ER doctors had sent me home, they’d told me I could bet on those odds. But a heart is not a nation. Mine was just unlucky. Or maybe lucky, because a friend who understood the odds, or pain, better than I did insisted I return to the hospital.

I didn’t want to miss the debate. That’s how I thought then, as if hate was something you had to see, over and over, something from which you couldn’t look away. Trump’s words didn’t matter. Neither did Clinton’s. It was too late, I realized. I’d prided myself on calling him a contender from the day he’d descended the golden escalator. “Wow, whoa,” he’d said. And, “They’re not sending their best”—Mexico, remember. And “They’re rapists”—the people “they” were sending. That’ll play, I’d thought. I knew how to think ugly then. I’d been looking at hate for a long time. It’d become my beat, my livelihood. I listened. I learned the vernacular. Love languages? My specialty was discerning hate languages, the hate that claimed its name was “love” and the hate that flattered itself as “tradition,” the hate that declared itself a “right” and the hate that cried—like Mel Gibson in Braveheart, a big movie across the American hate spectrum—“Fr-e-e-e-e-dom!”

I’d spent that spring traveling to Trump rallies. I told people Trump was an orator. They didn’t believe me. Not like Obama, I said. I’d pull up a video and hit mute. What do you see? I’d ask. They’d watch the chopping hands. “Mussolini,” they’d say. Right, now look again. Sometimes they saw what I saw: his timing. “Oh my God,” they’d say, “he’s like a comedian!” I’d turn on the sound. “Now listen.”

That’s how you learned to understand what he was really saying. That’s how you got the joke, which was not funny. Once you got it you were sorry. Sorry you’d looked; sorry you’d learned how to listen.

By April I thought he could win. By October I let myself imagine he might not. That night in the hospital I knew he would, and that when he did, if I was still around, I would come to my senses. I would look away. I would learn to stop listening. At least for a while.

It can be hard to really look at hate, especially if you’re like me, white, or, even more like me, a straight white man with a good job, who learned at age twelve from an Eddie Murphy Saturday Night Live sketch, “White Like Me,” just how much was granted me for my pallor. Murphy, mocking a best-selling book, Black Like Me—in which a white man investigates race in America by traveling around New York City in blackface—conducts an undercover investigation in whiteface, as a “Mr. White,” for whom a white banker overturns a loan rejection by a Black banker. “Just take what you want, Mr. White,” the white banker says, pushing money at Murphy. “Pay us back anytime—or don’t, we don’t care!” Once you get the joke, it’s everywhere. Consider Trump, Deutsche Bank. Or forget them. If you’re white like me, consider what you’ve been given, the debts you haven’t repaid. It can be hard to really look at hate when hate, as much as love, made the world in which you prosper.

But then, it’s hard for anybody to really look at hate, at what’s “toxic,” as we say now, allowing the metaphor to harden until it becomes jargon, inadvertently another means of looking away. It’s hard, should be hard, to reject it and yet to study it, to pull it back toward you, closer. To risk empathy, if not sympathy, for the devil, to attempt understanding, if not identification. It’s hard because you know about infection. You won’t become a white supremacist, but you’ll feel it in you anyway, the hate, even if it’s not yours.

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

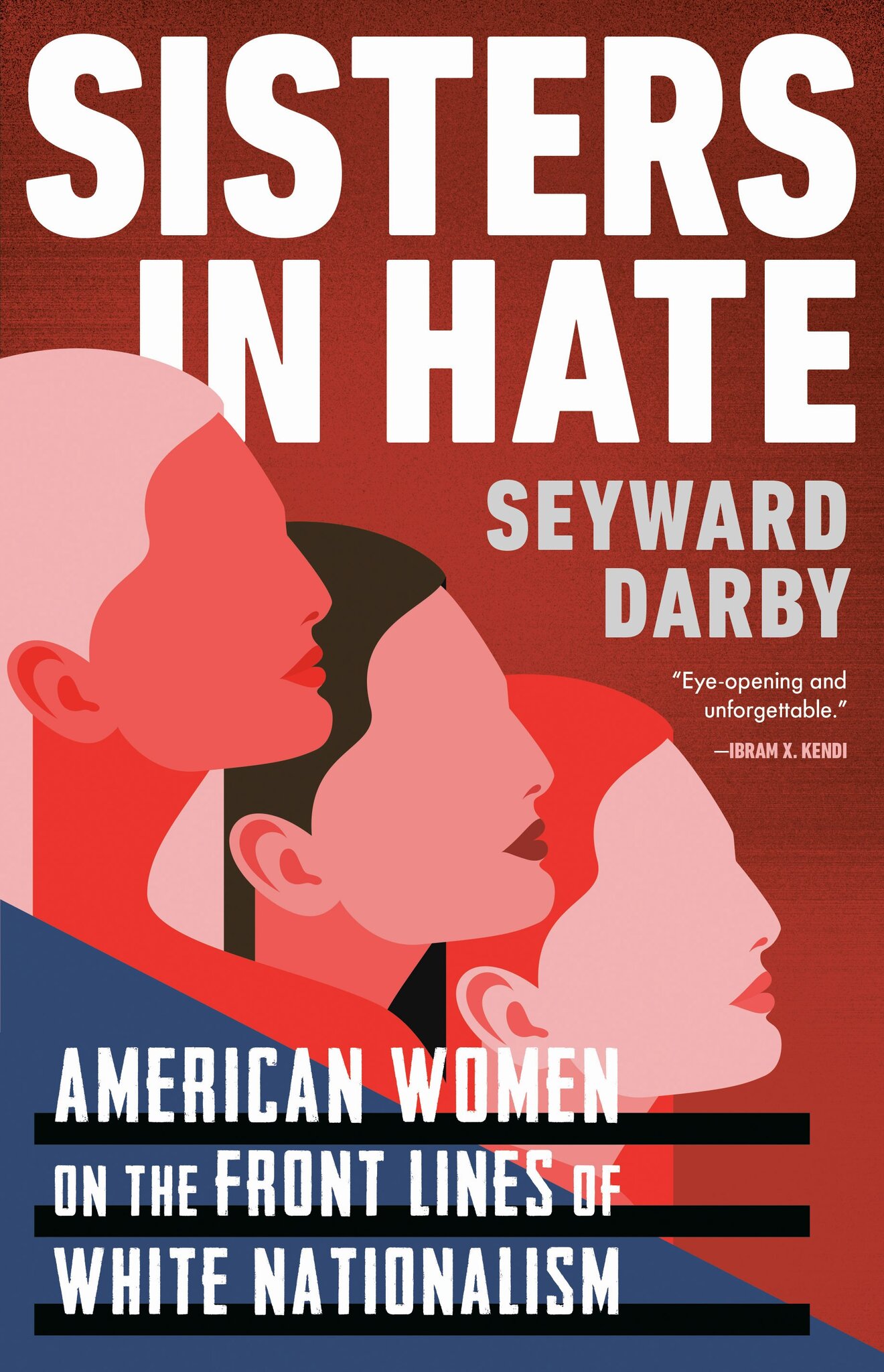

I STARTED WRITING THIS ESSAY on the hate under which we all now live the night of Trump’s first debate with Joe Biden. I was trying to think through two new books, Seyward Darby’s Sisters in Hate and Jean Guerrero’s Hatemonger, both smartly reported and urgent. But I stalled. I could read the books, but I didn’t know if I had it in me to write about them. I’d learned, like so many of us, to look away.

I hadn’t given up the hate beat entirely since my heart attack. I’d grown careful.

Last fall, when I started reporting on Trump rallies again, instead of drinking my fear into submission afterward, I’d go for long walks. I read these books while walking the dirt roads where I live now, roads so quiet I could walk and read. But often I’d pause, neither reading nor walking. I considered the question of how to write about hate, what these books—Darby’s, on the internal lives of female leaders of what remains (for now) fringe white nationalism, and Guerrero’s, about Trump senior adviser and speechwriter Stephen Miller, who is mainstreaming those beliefs—might say about the taxonomy of hate, the methodology of its study. As if looking at hate was a matter of professional curiosity.

I had thoughts! But I couldn’t keep what I’d read in my mind, my gut, my—maybe you’ll forgive the cliché—my heart. I’d reached saturation. Or maybe I was finally getting it, the “joke,” which is that you don’t need to go looking for hate. It’s always right there, mundane. I remembered a 2017 New York Times profile of a suburban neo-Nazi, how many accused it of “normalizing” its subject. I hadn’t thought much of it—no need to play neutral with fascism—but I hadn’t agreed when people said it didn’t matter if the Nazi liked Seinfeld and Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim. I thought there was no “normalizing” him, because he was all too normal. It seemed critical to understand the ways in which the antifascist del Toro’s art could be repurposed as hate. If it could happen to del Toro it could happen to anybody. We are, none of us, especially given the whiteness—the anti-Blackness—coded within us all by white supremacy, as far from the Nazi as we want to be. My problem with the Nazi next door wasn’t that we knew too much about him. We didn’t know enough.

I thought about that Nazi often while reading Guerrero’s Hatemonger. I felt ashamed when my wife saw me reading it. Of all that there is to study, I was choosing this? What was it? This thing we call Stephen Miller? Do we need to know?

Or rather, exhausted by the daily death toll, frightened of disease, facing the reality of a broken nation that won’t be healed—that refuses healing—do we need to know more than the fact that he is there? Stephen Miller may not be the Nazi next door, but he is inside 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, “the nation’s house,” whispering in Trump’s ear, funneling internet-cesspool white supremacy into policy. Policy. Wrong word for the interests of a man who cannot sleep at night so consumed is he by thoughts of ways to take children from their parents and who feeds Trump the tales of decapitation and eye gouging and heart carving and rape with which the president rallies his crowds to an actual screaming frenzy. The first time I saw Miller, in 2016, he seemed so sickly pale and cartoonishly sinister, so dead-eyed and spittle-flecked, that I puzzled over why Trump let him take the stage. “Are you ready to show them who’s really in charge?” he shouted at one of those rallies, reported on by Guerrero. “Are you ready,” he asked, “to do something they will write about for a thousand years?” A thousand years? Isn’t that a little too on the nose? You’re giving it away, Stephen!

Yes, replies Guerrero, bringing us into teenage Miller’s bedroom—see the movie posters on his walls, Casino, Goodfellas—as he developed the style of a Hollywood gangster, the mafioso gestures carefully copied from De Niro. Look closer, says Guerrero. Listen. Miller, like Trump, brings a new language to the public square. It is named most clearly by David Horowitz, Miller’s mentor since he was a teenage right-wing radio star. The founder of the “David Horowitz Freedom Center School for Political Warfare” placed Miller in his first job, with former Representative Michele Bachmann (based on their shared animosity toward Islam), his second, with former Representative John Shadegg (with whom he demonstrated alongside neo-Nazis), and—prelude to power—his third, with then Senator Jeff Sessions. It was while Miller was with Sessions, in 2012, that Horowitz sent Miller a blueprint for the reconfiguration of the GOP: “Hope works,” Horowitz wrote, examining Obama’s victory. “But fear,” he observed, anticipating Trump’s, “is a much stronger and more compelling emotion.” Fear and its fruit, hate—Horowitz recommended it as well—are not subtext. They’re meant, just as much as Miller’s mafia style, to be seen and heard for what they are. That, Miller understands, is their efficacy.

You see how this works? I said I’d gotten stuck, that I couldn’t hold on to enough of the details of hate to regurgitate them here. But I had it in me after all. The hate. Consider the last two paragraphs. The first is personal, an expression of revulsion, a mockery as a means of pushing it away. The second is political, the hate made plain and practical. Which demands our attention? From which should we—for our own good, for the sake of our hearts—look away?

Guerrero and Darby do not look away. They neither mock nor shudder, they analyze but they don’t dissect. They don’t fool themselves into thinking their subjects are containable by theory. They each study hate through deep reporting, informed by scholarship, in the service of narrative: literary journalism, the art of fact. They ask, What can we learn about hate if we tell a story about it?

Stories, of course, even true ones, require the imagination of both writer and reader. Darby and Guerrero ask the reader to learn about hate not just by understanding it as a specimen under a microscope but by imagining what it feels like for the hater—by inhabiting, if only briefly, the experience of hating. Here, Miller, or at least Guerrero’s account of him, allows us only so much. She presents him as an almost-structural outcome of changes in his native California. The state of his childhood that in 1994 reelected a governor, Pete Wilson, who ran against the specter of a Mexican “invasion”; the Santa Monica of his high school years that epitomized an affluent liberalism, long on concern for the poor but short on room for them, that Trump would look upon as material.

The most compelling insight into Miller comes from a middle school friend named Jason Islas, a working-class Mexican American whom Miller abruptly renounced one summer for both his Latino heritage and his class. Islas sees Miller as “the shadow self of [the] white, upper-middle-class liberal identity politics” of Santa Monica, in which they both saw hypocrisy. Islas wondered why, to afford housing, his mother had to remain with an abusive husband. Miller wondered why liberals didn’t just own their privilege or even take pride in it. “Islas fought it,” Guerrero writes; “Miller came to embody it.” Islas cites an episode of Star Trek, one of the shows over which they once bonded, called “Mirror, Mirror,” in which the Enterprise’s crew is replaced by evil doppelgängers from a parallel universe. That’s Miller, says Islas: “the mirror image of the world he came from,” an inevitable negativity—a kind of political antimatter.

In Darby’s Sisters of Hate we observe a more human devolution. Early on, there’s an aside dedicated to a former white nationalist—called “Rae” here—who left the movement and reflects on the steps that led her to it in the first place. Nothing too surprising for anyone who’s been through an American high school: Rae was bullied by girls but older boys paid her attention, which mattered more to her than the swastikas they spray-painted on walls. She in turn began paying attention to the race of those who bullied her; they happened to be Latina. Rae “started carving little swastikas into her skin.” You begin by being hurt; you proceed to hurting yourself; and for many by that logic you’ve earned the right to hurt others.

Darby cites sociologist Kathleen Blee, who writes that hate is “a process rather than attribute.” Or, in Darby’s more eloquent and ominous phrasing, “a thing achieved as much as felt or believed.” If the end-state of hate provides a lens through which to look at the world in terms of “white” and “Black”—to haters Black means not just people of African descent but all they find other, just as their “whiteness” erases most of their own ethnicity—Darby reverse engineers the construction of that lens through portraits from which emerge not so much conclusions as possibilities. Better ways to look at hate; and, maybe, better ways to look away.

She begins with a woman named Corinna Olsen, who like Rae has left white supremacy behind. The definitive trauma of her life was the drowning death of her younger brother. He’d been a skinhead, so in her grief she researched skinheads. (Later, too late, she’d realized that he’d aspired to be an antiracist skinhead.) Her first stop was the granddaddy of internet hate, Stormfront. But she saw love. Love for her skinhead brother, and then love for herself, because she loved him, because she’d looked for him. Stormfront taught her that self-love meant loving her whiteness, her “heritage,” a powerful term for a rootless young woman looking for shared identity. The stronger this “love” grew, the more necessary she found its opposition; she measured her love by the strength of her hate. And hate rewarded her with yet more love in the form of fellow travelers, friends, brothers. “In a perverse twist on the cliché,” writes Darby, hate “takes a village.”

Another one of Darby’s subjects, Ayla Stewart, aka “Wife with a Purpose,” found her village in the social media “tradwife”—traditional wife—community. Corinna, largely indifferent to religion, made torture porn on the side; Ayla, whose Christian nationalism is inextricable from her white nationalism, makes pies. But it’s not as simple as that. Once, she was a feminist. Presenting her master’s thesis on women’s spirituality, she described herself as a “radical, primal mama.” She found her voice online through a leftist blog, Mother, Lover, Goddess. She converted to Mormonism, but insisted on bringing goddess worship with her. She saw herself as subversive. When Texas removed four hundred children from a fundamentalist LDS compound in 2008, Ayla knew which side she was on. Fundamentalism represented resistance to power; and if that was so, what else had she seen upside down? Being a radical mom morphed into maternalism, a sanctification of mothers she found honored in the (white) past. Gradually, her whiteness moved out of its parentheses. Like Miller, she wanted to own her privilege. Her privilege became pride, and that gave her power. When GOP Representative Steve King tweeted in 2017 that America could not “restore our civilization” with “somebody else’s babies,” Ayla issued a “white baby challenge” to her growing following: “I’ve made 6, match or beat me!”

Ayla has since been “deplatformed” from most social media. One of her last appearances was a taped speech she had planned to give at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally, after which she mourned, in a sense, the death of Heather Heyer, murdered by a white nationalist in a Dodge Challenger. “God rest her soul,” Ayla tweeted. “She was clearly morbidly obese.” Heart attack, said Ayla, blaming not her killer but the men in Heyer’s life who’d allowed her to be in a dangerous place. Like a good mother, a good wife, Ayla had stayed in on the night of the torches and the day after. Now she is quiet. No more memes. It is a time for men. “I do believe,” she wrote in her last post, “we are entering a post-internet time for conservatives.” Yes; IRL; stand by.

HERE IS WHERE THIS ESSAY originally stalled. The point at which the hate on the page began to seem too contiguous with the hate right now to merit mention. By then Trump was in Walter Reed, lying or dying. Did it really matter which? I didn’t share the excitement some felt at the prospect of the latter. Would Pence make it better? Would our brutal wishes? I wouldn’t judge you if you were one who longed for narrative resolution, a fitting end to an ugly story. I wouldn’t call that hate. Schadenfreude might have been the most human reaction to the illness of a man whose disinterest in anything other than himself made possible the lonesome and gasping deaths of some 200,000. It’s 219,252 as I write, and I can’t imagine—I can’t grasp these numbers anymore—how many gone when you read this.

My rejection of schadenfreude wasn’t a matter of virtue but of trying to reclaim a feeling I had a month after that debate with Clinton. November 9, 2016, a morning on which I think I was the happiest leftist in America. I woke up and thought, fascism is here; and how lucky am I to be alive! To become aware of the anything-but-inevitable beat of one’s own heart after that heart is scarred, some piece of it beyond repair, made other, plastic and metal, sustained by daily dosages that must never be forgotten, is to experience an undercurrent of thanks.

And guilt. The hate from which, through the grace of gratitude, I looked away was also my “heritage,” my whiteness. Whiteness is not real. It’s hate’s imagination, that which is imagined by hate. A fiction—a story—and yet still as deadly as a Dodge Challenger and the viruses we can’t see.

What is to be done? To look at hate, as Trump innately understands, is to feed it. It will grow, within you as well as beyond. There is no PPE. Hold hate at a distance, and you’ll fail to see what’s coming until it chokes you. Pull it close and it’ll inhabit you. If you’re lucky, you’ll only be scarred. If you’re not, like Olsen and Ayla you’ll become possessed, or, like Miller, consumed.

If this was a proper review, I might in conclusion come to Darby’s third and cruelest subject, Lana Lokteff, find in her story a neat little resolution of all the other stories of wounded women and this wounding man—or of the writer who turns away and the writers who keep looking. I’d note the throughline of Trumpism in these stories—he is and will be our preexisting condition, for how long I don’t know, since I can’t say when, if ever, it is safe to stop listening for danger—and extract from it all some recommendations. I’d quote from Darby and Guerrero, maybe, or synthesize from their insights and my own from my days on the hate beat, my troubled walks since.

None of that will be forthcoming. But here’s Lana: forty-one, a daughter of grunge who gravitated to esoterica by way of Coast to Coast AM, the late-night radio program sympathetic to every conspiracy. Such “questions” led her to her husband, a Swede with whom she’d develop an increasingly popular white-nationalist platform called Red Ice. First UFOs and anti-vaxxers, then the Illuminati. Every conspiracy tilted her rightward. Eventually there were the Rothschilds, Jews, and ultimately the whiteness. The Whiteness. The deathward gravity of every plot, as Don DeLillo wrote in Libra, his 1988 novelization of JFK’s assassin. “A narrative . . . is no less than a conspiracy of armed men.”

It isn’t getting better. To look at hate, or to look away? Dying or lying—does it really matter which? I’ll try again. That’s what we can do, with hate, that which is within us and that which looms: try again, even as we understand the odds, because we understand them, the 95 percent certainty of failure no matter who wins. Try again: hoping “to observe Lana in her element,” Darby suggests to the fascists they might do something ordinary together, like people do. Grocery shopping, for instance. Lana, she writes, “seemed amused.”

“How someone brushes their hair, and how they pick up a glass—do you write about that kind of stuff,” she asked.

Readers are more likely to see subjects as nuanced humans, I suggested, if writers show them in their real lives.

“I’ve never appreciated that style of writing,” said [Lana’s husband]. . . .

“Yeah, we’re not novel readers,” Lana agreed.

If this seems a dead end, a blankness like that of Stephen Miller, Darby recognizes in it a different kind of truth. “In white nationalism,” she writes, “surfaces are everything: how people look, how history seems, how the future might be.” There—there’s the wrinkle in hate’s tautology, the flaw in its self-fulfilling prophecy. How history seems may be a surface, white or whitewashed, depending on perspective, but how the future might be—that is unseen. Look or look away, it’s still coming, the 5 percent no more or less than the other 95, every one of our chances, no matter how battered, possible until they’re not.

Jeff Sharlet is a journalist and the author or editor of seven books. His latest is This Brilliant Darkness: A Book of Strangers (Norton, 2020).