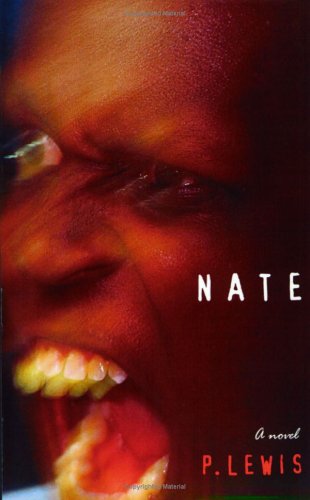

LAURENCE STERNE DESIGNATED the poet and novelist Tobias Smollett a “Smelfungus” in his 1768 novel-length travelogue A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy. Smollett published his travelogue Travels Through France and Italy two years before, and Sterne’s punishing evaluation of that work is as follows: “The learned Smelfungus travelled from Boulogne to Paris,—from Paris to Rome,—and so on;—but he set out with the spleen and jaundice, and every object he pass’d by was discoloured or distorted.—He wrote an account of them, but ’twas nothing but the account of his miserable feelings.” That judgment could equally apply to P. Lewis (aka Philip Lewis), whose 2006 novel Nate, long out of print but now available as an e-book, recently came to my attention when I read an Ishmael Reed interview. Reed was ranting about crime novelist Richard Price, author of Lush Life and Clockers. “His fake ghetto books have bought him a townhouse in Gramercy Park and a home on Staten Island while P. Lewis, author of Nate, one of the best African-American writers since Richard Wright, had to self-publish his book and sell his books in the subway.” I immediately purchased a Kindle edition of Nate from Jeff Bezos for about two dollars. Reed’s praise was not mere hyperbole. Nate’s clear, observatory power comes from the author’s unmitigated rage against a world built on hypocrisy and spite. Lewis roots through the detritus of the American state in order to display the vital messages he finds in the ruins.

Lewis’s first novel, Life of Death, published in 1993, was an unsparing satire about a Black dishwasher in Washington, DC. Though Life of Death received little critical attention—perhaps because it refused to offer hope for its characters—it established Lewis as a relentless portrayer of disenfranchised life, providing example after example of the ways that powerlessness leads people to annihilate each other. Regardless of color or gender, the cartoonish denizens of the novel’s Dummheit Cafe are ready to maul each other at the slightest provocation. To that end, they aren’t so different from the characters of Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night, and Lewis shares the Frenchman’s passion for elliptical barbs and outbursts mocking the futility of every character’s pursuit. Consider this passage in which the narrator must dismantle the innards of a dishwasher, moving his hands through the refuse—“lima beans, blood, string beans, broken plates, a few rotten teeth”—as he attempts to clean it: “It was all nauseating . . . the whole thing, all of it, from start to finish. The most dreadful thing was to get up in the morning thinking that I’d have to go through another day of it.” The rot and decay of existence is balanced with the drudgery of the repetitive manual labor required to get by, and thoughts like these lead the narrator Louie Phillips (get it?) to wonder just how necessary it is to feed people who often “throw their scraps on the floors and slobber all over the tables.” He tries to flee, but he is thwarted by his family, his lack of money, and his fear.

Nate, Lewis’s second novel, somehow intensifies this first book’s vision of the ways American society forces its Black and working-class citizens to cage themselves. He is suspicious of all portals that supposedly lead to a utopia outside of this system. Lewis takes a magnifying glass to the two institutions that have historically promised equality and advancement to Black people: the Black university (Lewis himself is a graduate of Howard) and the military. The book’s protagonist, Nathan James Morris, gets kicked out of Freedom College due to an incident that is never quite explained, and he joins the army. After realizing he can’t really hack the racism and torture from his fellow soldiers, he decides to leave. But he doesn’t get far. Nate’s parents are convinced that he is a lazy loafer, and his drunken father leads him, at gunpoint, out of the house and into the arms of the military police.

This is a common sequence of events in Nate. It’s always Groundhog Day, but the lesson here isn’t that repetition enables one to learn from one’s mistakes. Instead, Lewis portrays a world of continual violence and opprobrium; any attempt by a Black American to flee society’s binds will be met harshly. It’s as if at some point God forgot that he had placed a bet with the Devil, and Job continued to suffer on repeat, his life getting worse and worse without anyone being called to stop his descent. After Nate’s kidnapping, he is forced back into service and dispatched to Numidia, a fictional North African country, in order to aid the occupation of the region. He witnesses his colonel—a man who monitors his soldiers like a “general manager of a restaurant dutifully inspecting his dishwashers and busboys”—order the massacre of civilians. As soon as he gets the chance, he goes back to the United States in order to attend Coon State (the same HBCU Louie Phillips drops out of in Life of Death).

On campus, everything has been blasted to shreds: “Broken bottles were scattered casually along the campus walkways; the garbage cans were packed to overflowing; many of the lampposts lining the walkways were busted, as were not a few of the hall windows.” Nate wanders through a world coated with detritus, wondering if the decay on the ground reflects the decay of the institution. He wants to be a painter, but he is stymied by the arrogance of his professors, the hatred of his fellow students, and the paucity of his tools. He’s taunted about the way his clothes look, and when he attempts to purchase a shirt at the clothing store, he is robbed: “The honky took the wallet, went directly for the ID’s, pulling each and every card out, VISA, Master Card, etc., etc.” In this extreme capitalist critique, every store in the mall is run by literal thieves. To Lewis, the make-believe world of advertisement is transparent (at some point Nate drinks a can of soda that has been branded as “NIGGER!”: “No joke—that was the name of Numidia’s favorite soft drink, bottled by our very own Coca-Cola for exclusively overseas distribution”), and his satire draws its power by making what is obvious to him plain to us.

Lewis doesn’t just vent his spleen at white American society; he’s disgusted with Blacks who support the status quo even when they pretend to fight against it. Lewis is also perspicacious on the subtle ways that American society degrades Black people. His foil for Nate, Guy Sellers, is an almost-supernatural alpha-male who follows and destroys Nate wherever he goes. When Nate is in the military, Sellers bullies him; when Nate is at Coon State, Sellers introduces him to heroin and whisks him away to Turkey; wherever Nate is, Sellers makes his life a living hell. Yet Sellers’s malignancy has a purpose: Lewis illustrates how confused and hateful men are the products of a society that has twisted notions of masculinity. Sellers dates many women, but he is also ashamed that he wants to be a woman. Sellers aspires to be an artist and a writer, but he cannot give his art a shape. Late in the novel, Sellers and Nate are living together, and Nate peeks at Sellers’s computer to see what Sellers has been so busily writing. What he views surprises him:

No words, only bright, flashing, shimmering colors that, upon closer scrutiny, turned out to be the image of rolling fields of lilies. Looking still closer, this innocuous image of lilies appeared to be . . . singing. Yes, that’s right. A whole field of singing lilies, with, God help us, Guy Sellers flying above, clad in a white robe. He, too, like the lilies, is singing soprano—a sweet, sickly putrid voice that makes me want to hibernate in shame. Why, may you ask, this sudden changeover from New Jack hoodlum to Whitmanian post-modernist?

Sellers’s tragedy is his inability to be either. The “hoodlum” character is the permanent disguise he must wear in the world; and as a “Whitmanian post-modernist” he will never gain acceptance into the literary community, because the shape he takes will never fit the accepted mold of a “Black writer.” With Sellers, Lewis suggests that the constant shape-shifting of a Black upstart will eventually lead him to insanity, once he recognizes that the world he accommodated, causing him to lose himself, has no place for him as anything besides a terror or a joke. Sellers’s pain is somehow worse than Nate’s. Though Nate’s oppression is more visceral—he is slapped, punched, urinated on, and worse—he at least knows he exists, because he feels pain. Nate feels himself slipping away when he gets addicted to pain pills or is injected with Sellers’s heroin: “When I saw my blood coming up through the dropper after his heroin entered me, it was like my soul was going inside it, only to be hurled into the trash.”

Such dissipation is the opposite of the resolve Nate displays in the hospital after a lover makes an attempt on his life; there, he is mocked and tortured by an intoxicated medical staff: “These white-robed assholes were enjoying themselves watching me die, and it was as real as it could ever get. . . . Goddammit, they must have thought, this punk can’t die. He’s not like these other niggers: he’s dangerous, he’s got self-respect, and he’s got a will to live. How they hated him for it.” For Lewis, a rigorous evaluation of the world brings pain, but this is the only way to confront the ubiquitous abuses and lies. A smelfungus may be harshly judged, and may look at life through a darkened hue. But the insight such a writer brings to our affairs is necessary, and Nate is a necessary book, with a perspective that is dangerous to ignore. “I had consistently overestimated my countrymen as a nation, as a people,” Nate reflects. “But now I despised them. Not, mind you, for racial reasons—though I certainly had no reason in hell to love white people. No: I hated them, every single one of them—Black, white, Latino, Asian, Arab, Jew, Turk, Orthodox, Buddhist, Seventh-Day Adventist—because I knew just who and what they were.” Rather than cloud his vision, vitriol clarifies it.

Hubert Adjei-Kontoh is an associate editor at Pitchfork.