GET BIG FAST was an early Amazon motto. The slogan sounds like a fratty refrain tossed around at the gym. Jeff Bezos had it printed on T-shirts. More than twenty-five years after leaving his position as a Wall Street hedge-fund executive to found Amazon, Bezos’s size anxiety is long gone. (At least as it pertains to his company; the CEO’s Washington, DC, house has eleven bedrooms and twenty-five bathrooms, a bedroom-to-bathroom ratio that raises both architectural and scatological questions.) Bezos is now worth $180 billion. Amazon, were it a country, would have a larger GDP than Australia.

Such numbers are nonsensically large—there’s no way to make them stick. But in 2017, Bezos demonstrated what they mean. That was the year the company conducted a nationwide sweepstakes to choose a location for its second headquarters, or HQ2, as it was called. Seattle was already a company town: Amazon had more than 40,000 employees there, and as much of the city’s office space as the next forty largest employers combined. It was time to take over a new city.

Local and state governments raced to undercut each other. It wasn’t only tax credits that in some locations amounted to over $1 billion; the subsidies offered to Amazon were a display of abject creativity. Bezos is a Trekkie, so Chicago had Star Trek star William Shatner narrate the city’s pitch video. Tucson, Arizona, sent a giant saguaro cactus to Amazon headquarters. Sly James, Kansas City’s mayor at the time, bought and reviewed one thousand Amazon products, giving every item five stars. But the locations Bezos selected—New York City and Northern Virginia—were always going to win. Together, the chosen bids gave the company over $3 billion in tax incentives and grants.

The spectacle was about more than financial benefits; the company sought to flex its power over elected officials. Amazon had engaged in these displays before, such as when it threatened to move jobs out of Seattle after the city council passed a law that would’ve taxed large employers for each employee earning over $150,000 to fund homelessness-outreach services. Indeed, New York had its winning status revoked after a coalition of working-class organizations, left-leaning politicians, and pissed-off residents made too much noise about the downsides of hosting HQ2. The point is to beg on one’s knees; ingratitude is disqualifying.

But the contest was also about Amazon’s life-blood: data. The company learned exactly what each location was willing to give up. It received a precise picture of the strengths, weaknesses, and points of resistance in each corner of the nation. How many NDAs would Alabama officials sign? What did Boston’s elected officials think the region’s future looks like? How many young people in Columbus were entering the workforce each year? How low would Orlando go? The HQ2 affair was a national demonstration of fealty to a private corporation by publicly elected officials. Sure, everyone already knew Amazon was powerful, but this was different: a corporate entity told politicians to jump, and they asked “How high?” How did this happen?

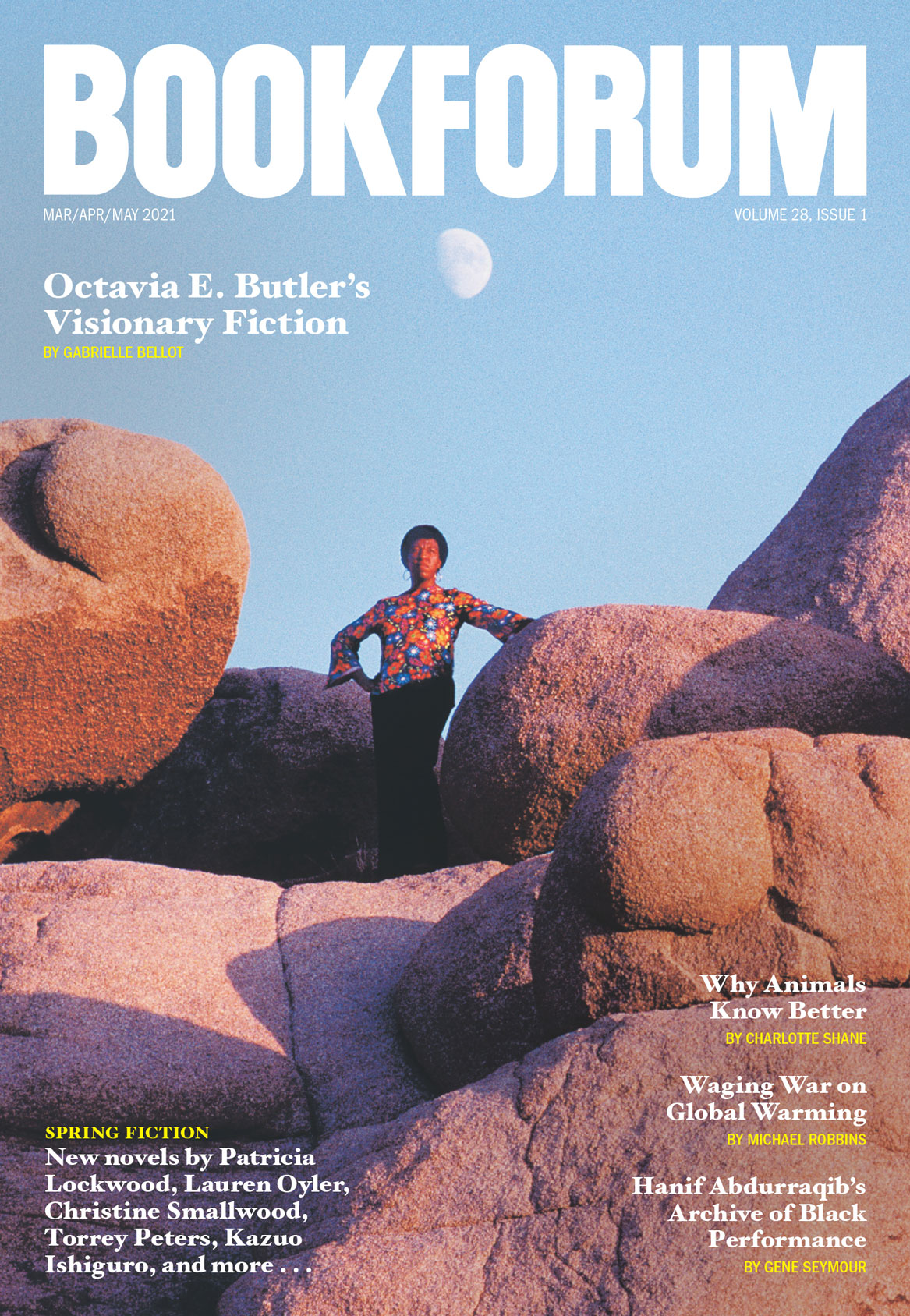

Alec MacGillis’s Fulfillment: Winning and Losing in One-Click America goes a long way toward answering that question. MacGillis, a reporter for ProPublica, investigates the country left in Amazon’s wake, crisscrossing the United States from what he calls the winning cities to those regions on the losing side. His contention is that corporate concentration creates geographic bifurcation. Places like Boston, New York, Washington, DC, the Bay Area, and Seattle win the lottery, attracting an influx of well-heeled residents. Capital divests from other areas—midsize cities in the Midwest, much of the Rust Belt—leaving them hollowed out. Low-wage jobs and drug addictions replace union benefits. But the division is internal to the winning regions too. Poor residents within the lucky cities suffer. Desperation reigns, expectations are lowered, and elected officials become increasingly willing to give Amazon anything in exchange for the promise of jobs.

Using the tech giant as a focal point allows MacGillis to show that this state of affairs was a choice, not an inevitability. It’s not that “good jobs left”; the transformation of work was engineered. Fulfillment meticulously documents how that process plays out, with the fate of millions haggled over by a handful of people in tucked-away conference rooms.

When Amazon wanted to build two new warehouses in 2015, it reached out to JobsOhio, a private nonprofit created by then-governor John Kasich to oversee negotiations over tax incentives with companies. “Every month,” writes MacGillis, “a board called the Ohio Tax Credit Authority approved the incentives negotiated by Jobs-Ohio.” On July 27, 2015, it was Amazon’s turn to meet with the tax board. The company promised two thousand full-time jobs. In exchange, it wanted a fifteen-year tax credit worth $17 million in addition to a $1.5 million cash grant from the state liquor-monopoly profits controlled by JobsOhio. The result? “The board approved the credit 4-0.”

Surveying Amazon’s operations in the state, MacGillis writes that “the company had, in a sense, segmented its workforce into classes and spread them across the map: there were its engineering and software-developer towns, there were the data-center towns, and there were the warehouse towns.” Amazon chose the Columbus area as its location for Amazon Web Services US East, and picked three towns north of the city for its centers. Hilliard, Dublin, and New Albany were “the right sort of exurban communities to target: wealthy enough to support good schools for employees’ kids, but also sufficiently insecure in their civic infrastructure and identity to be easy marks.” The company secured its standard extractions: a fifteen-year exemption from property taxes—worth around $5 million for each data center—accelerated building permits, and waived fees. It required the community to sign NDAs before negotiations could even begin. Dublin threw in sixty-eight acres of farmland for free, and a guarantee that the company did not have to contract with union labor.

The warehouses, by contrast, are south and east of the city, areas poorer than those in the north. The sites in Obetz and Etna are near I-270 and “close enough to the struggling towns of southern and eastern Ohio to be in plausible reach of a long commute for those desperate enough to undertake it.” Amazon’s warehouses come with the standard suite of exemptions—even though ambulances and fire trucks are often called to the locations, which one investigation showed have twice the rate of serious injuries as other warehouses, the company does its best to avoid paying taxes for emergency services.

Tax avoidance is foundational to the company’s empire. MacGillis enumerates a long, damning list of the company’s schemes:

There was the initial decision to settle in Seattle to avoid assessing sales tax in big states such as California. There was the decision to hold off as long as possible on opening warehouses in many large states to avoid the sales taxes there. Amazon employees scattered around the country often carried misleading business cards, so that the company couldn’t be accused of operating in a given state and thus forced to pay taxes there. In 2010, the company went so far as to close its only warehouse in Texas and drop plans for additional ones when state officials pushed Amazon to pay nearly $270 million in back sales taxes there, forcing the state to waive the back taxes. By 2017, the company had even created a secret internal goal of securing $1 billion per year in local tax subsidies.

This is predictable behavior for a company run by a man whose focus has always been on getting as rich as possible. But the government’s support for this cause testifies to its class character. A capitalist state takes its cues from executives. When a region has mostly low-paying work and little in the way of a social-welfare net, it’ll beg employers for jobs with a higher wage (even if that wage is below the industry average, as is true of Amazon’s warehouses). There is no neutrality, only officials groveling at Bezos’s feet, deferring to his fake-business-card-carrying minions. Working-class immiseration is the direct result.

The influence never ends. There is Amazon’s unparalleled lobbying: against the regulation of drones, which it hopes to use for delivery; for government procurement, as the company bulks up its relationship with federal agencies; against antitrust investigations. There is the trickle-down even to enforcement agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. When fifty-nine-year-old Phillip Lee Terry was crushed to death by a forklift in a Plainfield, Indiana, Amazon warehouse in 2017, the state’s OSHA director told the company how to blame Terry for his own death and negotiate down the fines. Not long after issuing citations and a $28,000 fine, the agency quietly deleted these penalties from the books. Indiana, after all, was hoping to get HQ2.

The past year has been a godsend for the company. “COVID-19, in our view, has injected Amazon with a growth hormone,” noted an analyst at Wall Street firm D.A. Davidson last summer. What was good for Amazon was never good for America, and now the evidence was irrefutable. In one four-month period, Bezos’s net worth rose by $24 billion. Amazon was already one of the largest employers in the United States, but in 2020, the company added more than 425,000 jobs around the world. It increased its workforce by more than 50 percent from the previous year; the New York Times compared the surge to the shipbuilders’ hiring spree at the start of World War II. By November, 1.2 million people worldwide were on Amazon’s payroll—a number that doesn’t include an estimated 500,000 delivery drivers. That workforce is contracted with a third party, saving the company from liability for accidents; most of their drivers, unlike those at other corporations, get their training by watching instructional videos on their phones.

Get Big Fast, indeed. As a motto, it’s reminiscent of the one used by Eugene Grace: Always More Production. Grace was the president of Bethlehem Steel Corporation for thirty years, overseeing the company’s stratospheric growth. By the middle of the twentieth century, its steel mill at Sparrows Point, near Baltimore, Maryland, was the largest in the world. Today, Sparrows Point is Tradepoint Atlantic, a logistics hub. Amazon opened its second warehouse there last year.

Alex Press is a staff writer at Jacobin magazine. She lives in Pittsburgh.