They’ll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed

—Langston Hughes, “I, Too”

WHEN HUGHES PUBLISHED THESE WORDS in 1925, Jim Crow’s rule over America remained at or near its peak. And so it was subversive optimism back then to envision a time when Black Americans would no longer be consigned, as Hughes’s poem delineated, to eat in the kitchen while everybody else sat at the table “when company comes.” Legally sanctioned segregation’s been subdued for decades now, but optimism’s still elusive no matter how much has changed in the almost hundred years since Hughes, “too,” sang America. Putting it baldly, it’s 2021 and America’s still struggling to sing along, even though we’ve been sitting at the table for a while. What do people now see at that table when they see Black people? Beauty, certainly; but as other poets have assured us, sadness and terror lurk beneath and bend around Beauty’s edges.

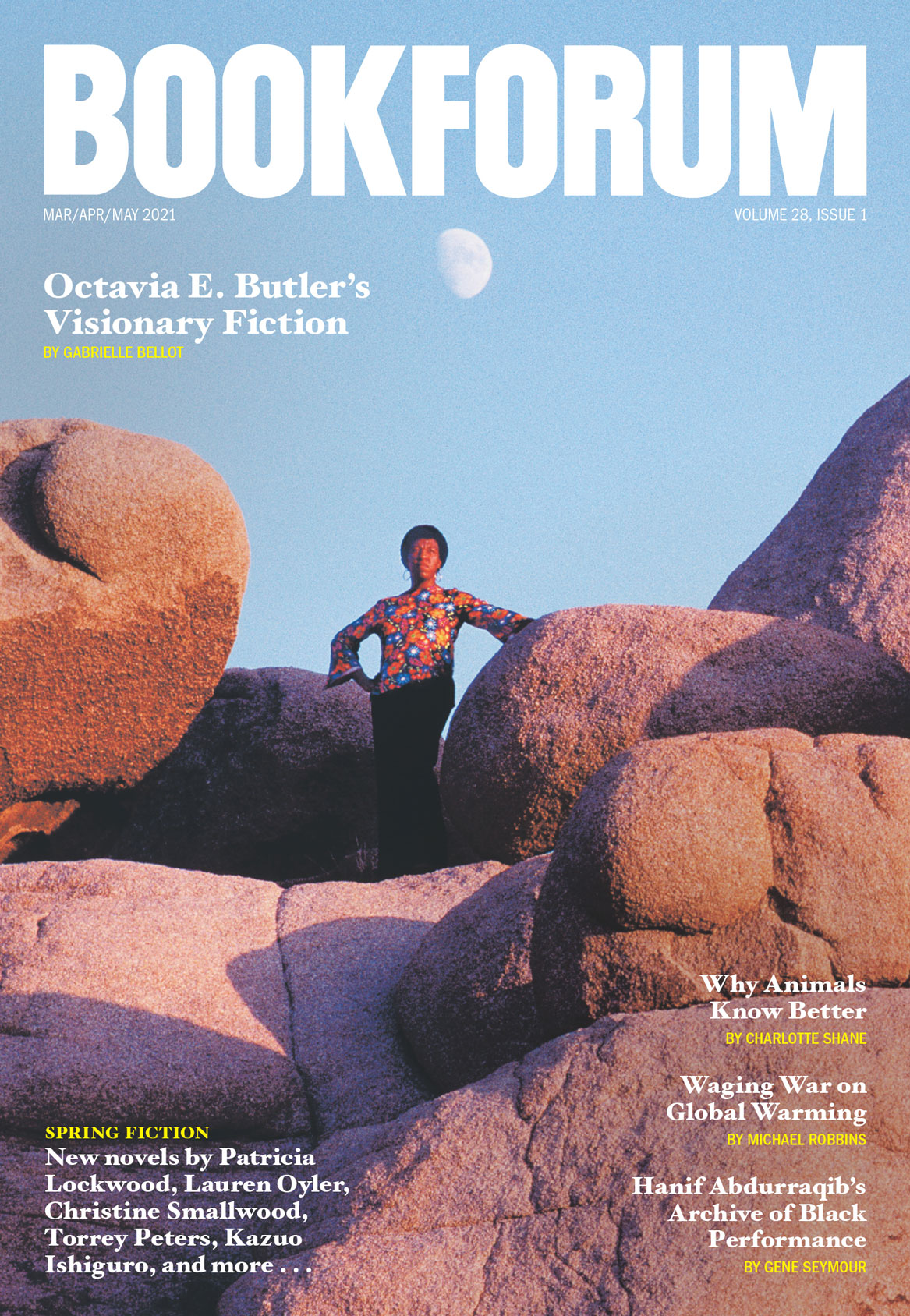

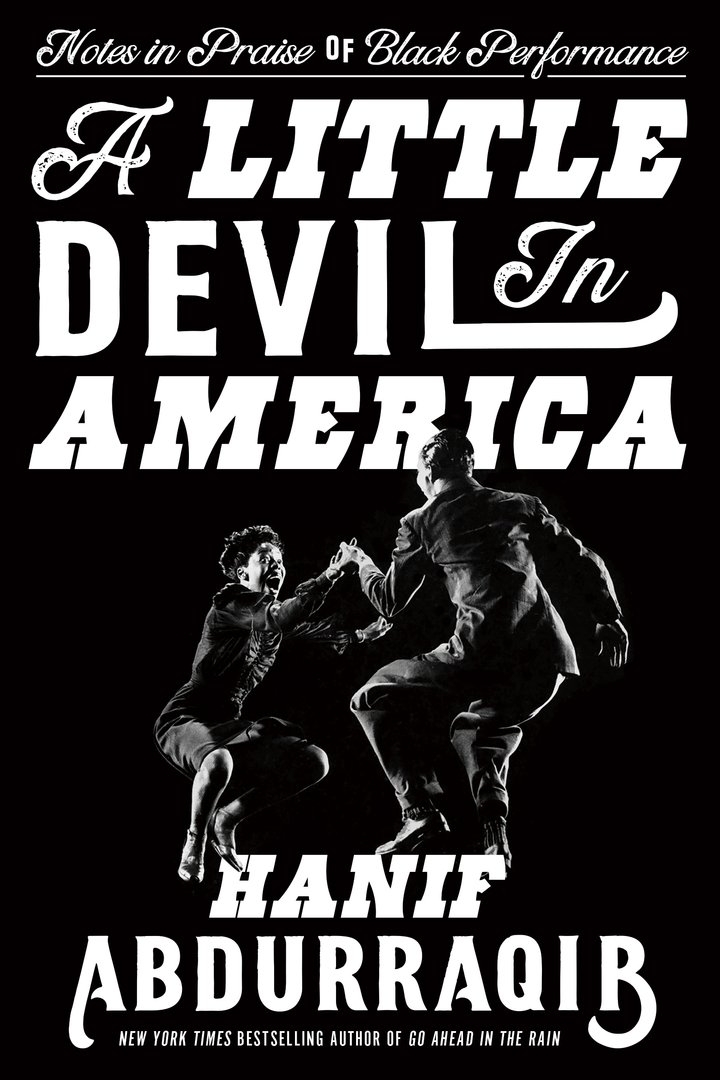

A Little Devil in America offers a wide, deep, and discerning inquest into the Beauty of Blackness as enacted on stages and screens, in unanimity and discord, on public airwaves and in intimate spaces. Its author, Hanif Abdurraqib, is a poet whose work is anthologized with Hughes and others in the recently published Library of America anthology of African American poetry. Abdurraqib, both here and in such previous works as his audaciously innovative 2017 essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us and his incisive 2019 “love letter” to A Tribe Called Quest, Go Ahead in the Rain, has brought to pop criticism and cultural history not just a poet’s lyricism and imagery but also a scholar’s rigor, a novelist’s sense of character and place, and a punk-rocker’s impulse to dislodge conventional wisdom from its moorings until something shakes loose and is exposed to audiences too lethargic to think or even react differently.

When, for instance, Abdurraqib submerges himself in the incessant pop-cultural trope of the “magical negro,” a stock device whose sole purpose is to guide white characters to better love lives, greater athletic prowess, or social enlightenment, the usual suspects—Hattie McDaniel’s Mammy in 1939’s Gone with the Wind, Will Smith as the eponymous ethereal caddy in 2000’s The Legend of Bagger Vance—won’t make readers’ heads spin as fast as his principal (and unexpected) example: comedian Dave Chappelle, for whom, Abdurraqib writes, “the laughter of white people was both currency and conflict.” Such paradoxes, indeed the whole idea of paradox, are to be vaulted, shoved aside, or embraced by myriad Black artists in Abdurraqib’s gallery, from science-fiction writer Octavia E. Butler to Afro-futurist jazz pioneer Sun Ra, from soul singers Patti LaBelle and Aretha Franklin to pianist Don Shirley. For all their accomplishments, these and other figures examined in A Little Devil in America remain susceptible to a variety of interpretations; referring to the depiction of Shirley as the Black buddy (or “magical negro”) to the white hero of the feel-good 2018 Oscar winner Green Book, Abdurraqib wishes the musician’s life would have been leased by a movie “that doesn’t manipulate his story to serve the American thirst for easy resolution.”

Making things both harder and easier for white America was, in Abdurraqib’s view, an overriding paradox of Chappelle’s Show, the phenomenally successful Comedy Central series that ran between 2003 and 2006. Its success was driven by its star’s brash use of sketch comedy to lead audiences, Black, white, or other, “to a less flattering reflection of themselves, for the sake of something in between absurdity and introspection.” Chappelle and his Black fans loved the mindfucks his show perpetrated with his portrayal of a blind Black Ku Klux Klansman; his “Niggar Family,” a ’50s-sitcom parody featuring a bland white suburban household bearing that borderline-offensive last name; and “Black Pixie,” in which Chappelle’s on a passenger jet faced with the choice of fish or fried chicken, a decision that summons a brazenly stereotypical tiny version of Chappelle in a bellhop uniform goading him to go for the latter. But by the time this sketch aired, Abdurraqib writes, “the people who knew they could sometimes painfully laugh along with [Chappelle] and the people who knew they could laugh at him were already two clearly defined lines.” Through such awkward bifurcation, “Chappelle got to be everyone’s Black friend for a while,” one who, for all his fierce racial pride and anti-racist insurgency, also “fulfilled [whites’] particular fantasy of permission granting.” Paradox, in this case, ended up hemming Chappelle in; his response was to cut the cord on his great achievement and split for South Africa to recuperate and recharge.

Decades before, the indomitable, dynamic Josephine Baker left a more institutionally segregated America “before [America] could persuade her to fall in love with it.” Once she was established on Europe’s stages and in its collective psyche, Baker’s ability to hold dominion over “the imaginations of men” gave her autonomy over her life, enabling her to perform throughout the Continent as a singer, a dancer, and, during World War II, an Allied spy for the French. When, after the war, she returned to her native St. Louis, Missouri, to perform a triumphant concert before an integrated audience, she used the occasion to remind the city of the racism that compelled her to escape to another country where she was better understood. In one of many interludes where Abdurraqib seamlessly spins off from historic narrative to personal reminiscence, Baker’s homecoming prompts him to contemplate his own return to his hometown Columbus, Ohio, after a three-year absence, finding it an “exhausting and dismantling city” where gentrification surges uneasily within a stubbornly polarized racial environment. This makes him “envious” of Josephine Baker, who, he writes, “did not need a city, or a country. She made herself bigger and more desirable than anywhere she could have been or been from.”

Abdurraqib cherishes this power to enlarge oneself within or beyond real or imagined restrictions. (His own range of interests affirms this, taking in not just hip-hop and punk rock but also, in They Can’t Kill Us, Bruce Springsteen, Carly Rae Jepsen, and Johnny Cash.) He exalts this capability in Baker and other women such as Merry Clayton, the quintessential backup vocalist whose incendiary rendering of the chorus to the Rolling Stones’ 1969 barn-burner “Gimme Shelter” all but overpowers Mick Jagger’s presence. And (almost inevitably) there is Beyoncé, whose opening act for the 2016 Super Bowl halftime show dared to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Black Panther Party’s founding. Abdurraqib reminds readers of the massive viewing audience’s shock and awe over seeing one of the world’s biggest pop icons appearing midfield at this least radical of American rituals, “flanked by at least two dozen Black women, each of them dressed all in black, perfectly coiffed afros radiating from beneath their black berets.” The pushback following this appearance, as Abdurraqib writes, “was often irrational,” citing Rudy Giuliani’s complaint that Bey’s show attacked police. (Abdurraqib: “Power, when threatened, pulls an invisible narrative from the clouds that only others in power and afraid can see.”) Abdurraqib’s own reactions to this big bold show are more complex and somewhat conflicted: he notes how transgressive its surface elements were to the Giulianis of the world, while warning that “even this type of performance on this large of a stage is divorced from the work of the people.” But in the end, he applauds “a message so loud it didn’t have to be spoken in order to be heard.”

Abdurraqib takes up a more problematic and more intriguing attempt to widen one’s personality within grandiose boundaries in his breakdown of Whitney Houston’s table-setting splashy performance of her hit “I Wanna Dance with Somebody (Who Loves Me)” at the 1988 Grammy Awards. Problem: “Whitney Houston could not dance. I have made my peace with this and I beg of you to do the same. . . . I am telling you that she could not dance to save her life.” The production was “so elaborate that it distracted from any of Houston’s dancing failures” with a welter of other dancers engaged in moves and routines designed to keep people focused more on Houston’s voice and her “high-waisted pants with a massive butterfly buckle at her waist.” (How very 1988!)

Yet, as peculiar and over-amped as this sounds in retrospect, Abdurraqib reflects that it offered an ironic affirmation of the song Houston was singing at that moment. A song, Abdurraqib writes,

that is more about forgiveness than anything else. . . . Consider what it is to want to feel heat in a way that is not sexual, but perhaps born out of rituals of shared space. . . . I want to dance with somebody who loves me. I want to dance with somebody who might forgive me for my failure. I want to dance with somebody who will know, as I do, that there are songs that summon movement even out of those of us who cannot dance, and I want to dance with someone who loves me enough to lie to me, until a record stops.

Dancing, whether as ritual, combat, or self-realization, is A Little Devil in America’s prevailing motif: its six sections are labeled “movements,” each opening with ruefully funny stream-of-consciousness reveries bearing the title “On Times I Have Forced Myself to Dance.” The rousing excerpt from his Whitney Houston essay displays how Abdurraqib’s prose compels one’s mind to dance, freely and joyously, to his discursive and polyrhythmic music. True, there are times when the shake-and-bake of his rhetoric can veer into overkill, or become evasive: an otherwise trenchant and detailed deconstruction of blackface minstrelsy and its persisting anachronisms is weakened somewhat when, in scolding Al Jolson’s ghost and threatening it with immersion in water to wash out his “dark coat of blackface,” Abdurraqib fails to acknowledge how Jolson’s minstrel-inflected showmanship was powerful enough to influence not just white rock pioneers like Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis but Black soul icons like Aretha Franklin and Jackie Wilson, who injected Jolson’s big-time vocal effects and flashy movement into their own stagecraft. Something about the seemingly insatiable hunger Abdurraqib shows for cultural transaction, paradoxical mischief, and Beauty in Blackness tells me he’ll get to such matters soon enough.

Gene Seymour is a writer living in Philadelphia.