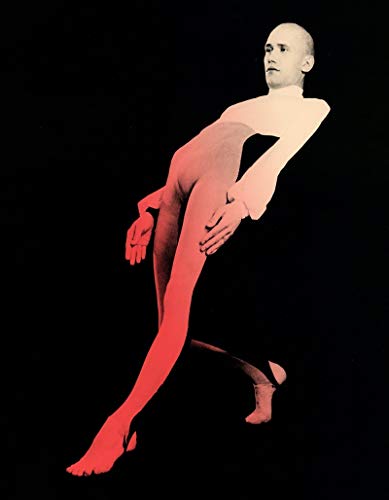

IF DANCE IS HUMANITY’S REBELLION AGAINST GRAVITY, choreographer Michael Clark defied dance’s gravitas. He was classically trained: first as an Aberdeen boy schooled in traditional Scottish dance, then as a star pupil at London’s Royal Ballet School, later as a member of the Ballet Rambert, and later still as a summer student of Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

Ultimately, Clark made his reputation by aerating the stuffy dance world, transforming the landscape with a punk ethos and the pointed exuberance of London’s queer club scene.

In 1984, at the prodigious age of twenty-two, he founded the Michael Clark Company, not only gathering together a corps of superlative dancers but also collaborating with like-minded provocateurs including the Fall’s Mark E. Smith, and the immortal masterpiece Leigh Bowery. Two years later, Clark and all were celebrated in Hail the New Puritan, the landmark film by artist Charles Atlas that brilliantly kinked the art/life line. Broadcast across the UK on Channel 4, it ends with the sweet-faced choreographer—his bleached mohawk proudly standing on his head like a tiara worn the wrong way—stripping down to his skivvies and performing an elegant solo to Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight”: a regal, cheeky production fit for the King.

In 2014, Clark was made a Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by the Queen for his services to dance—proof that he’s become a bit of an institution himself, albeit one with a dissident spirit. Published on the occasion of his first retrospective at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer captures the arc and whirl of the choreographer’s vivacious, audacious career. (Completists will want this catalogue on their shelf next to Michael Clark [Violette Editions, 2011], his first glossy monograph, because more is more.) Via essays, reproductions of ephemera, images of his wild performances and even wilder costumes, Barbican curator and the book’s editor Florence Ostende makes clear that Clark’s great gift, apart from the creation of dance, has always been his melding with other artists’ minds: “I choose collaborators with very strong ideas of their own,” he told her in an interview. “It thickens the plot.” It also atomizes any notion of auteurism. As sound artist Susan Stenger remembers: “It really seemed like he was making the sound visible and I was making the movement audible.” Such perfect syntheses might be considered his signature move, and leafing through Cosmic Dancer—titled after the 1971 T. Rex song to which Clark choreographed one of his most beloved works—one sees why his stages always feel like complete worlds. Bowery designed leotards to bare the dancers’ bums in 1984’s New Puritans, Sarah Lucas built the King Kong–sized arm that bobbed up and down on stage masturbating in 2001’s Before and After: The Fall: it takes many hands to build an iconoclast. The show and catalogue also honor how Clark’s power extends beyond theaters, impressing and inspiring painters like Elizabeth Peyton and Silke Otto-Knapp. Peyton once described his work as “so human and so now,” to which we should add: “so rare and so uplifting.”