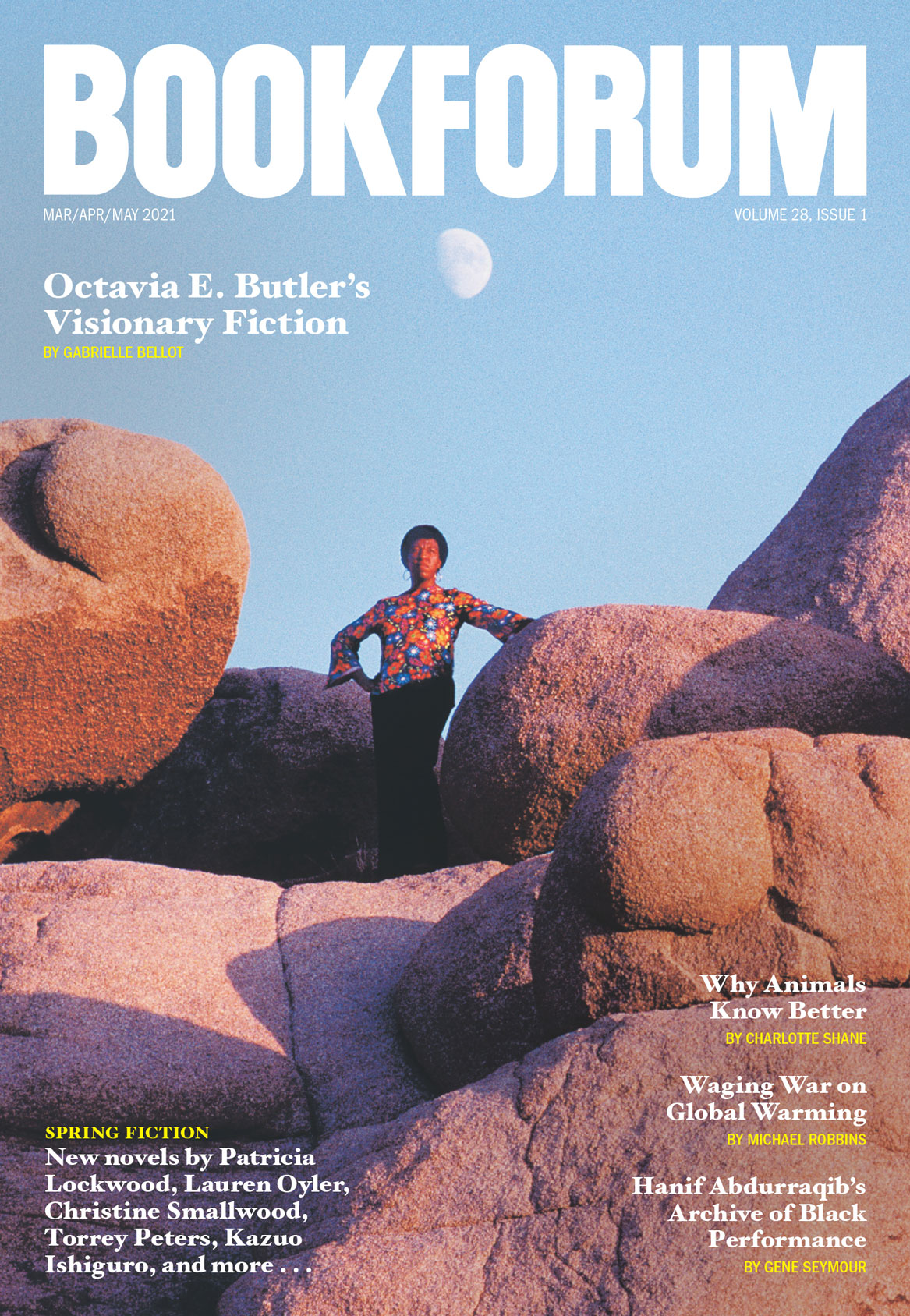

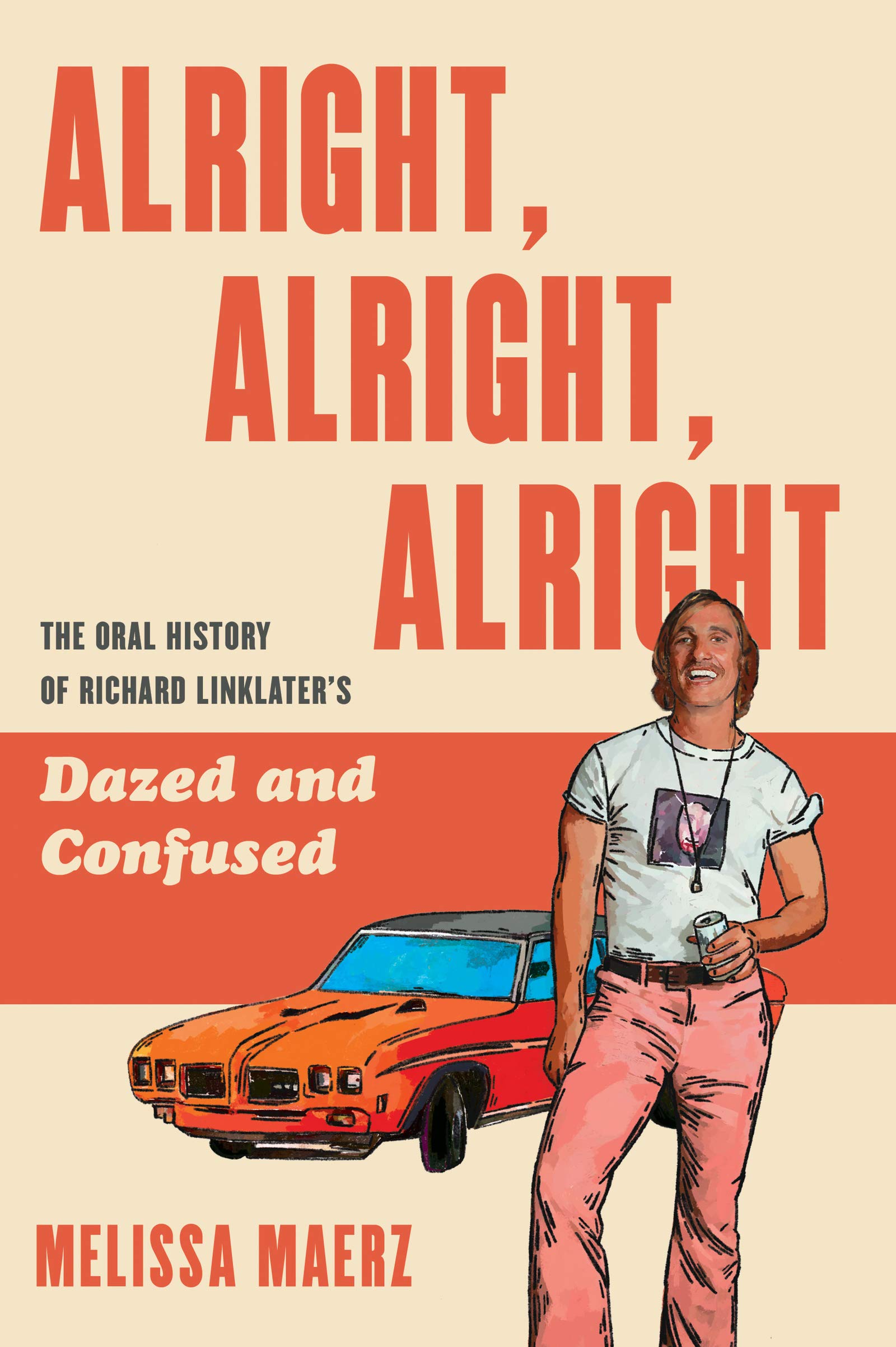

RICHARD LINKLATER IS A DIRECTOR I CARE A LOT ABOUT, but, sacrilegiously to some, his sprawling 1993 comedy Dazed and Confused, about the misadventures of Texas high school students on the last day of school in 1976, isn’t one of my favorites. I might feel bad about that, if Linklater didn’t agree. “I think it’s middling,” he tells pop-culture journalist Melissa Maerz early in her new book. “I don’t know why people latch on to it.” Despite poor initial box office, the film’s cult built up through video and its popular hard-rock soundtrack until it became a recognized classic, complete with a Criterion edition and now Alright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused (Harper, $27), Maerz’s commemorative oral history of its making and legacy. The book’s prime appeal is its font of anecdotes, drawn from more than one-hundred and fifty interviews, on the one hand about the trials Linklater endured getting it made, and on the other about the blast its young cast—including then-unknowns like Matthew McConaughey (he of the titular catchphrase), Ben Affleck, Parker Posey, and Joey Lauren Adams, all getting their first big breaks—had in their “summer camp” of shooting in Austin. Along the way, it effectively illuminates the sources of D&C’s charms and shortcomings, both for devotees and for skeptics like its director and me.

Maerz serves more as choir arranger than critic here, but she wisely highlights certain themes, and a chief one is nostalgia—the 1970s and teen nostalgia of the film’s subject matter, and the 1990s nostalgia it (and her own book) arouses now. Ironically, Linklater intended to make an anti-nostalgia movie, about the inevitable oppression and confinement of youth, rather than the affectionate celebration of adolescent energy and untamedness he ended up with. Linklater was thirty-one and had just made his name at Sundance with Slacker, the cheap indie he’d financed on credit cards and shot with a rough assortment of friends in the Austin bohemian underground. Its title would become synonymous with the skeptical anti-careerism that spurred a media panic about wayward Gen X. Coming from that milieu, an almost militant anti-nostalgia would have been de rigueur, since the claustrophobic ubiquity of 1960s nostalgia was one of that next cohort’s greatest irritants. But when Linklater then got a chance to pitch Universal Pictures, he sold D&C on the strength of it being an updated, stoner version of American Graffiti. Like any strong-minded director, he later wanted to play down the influence, but the fact is that D&C sticks pretty near the template of George Lucas’s 1973 teens-cruising-in-cars classic. So the concept was loaded with rearview mirrors within rearview mirrors from the first. The young director had no end of ideas for darker tangents it could contain, and many of them were actually scripted and shot. But then Linklater went through months of run-ins with the studio and his own producers over content, schedules, music, and more, including fighting not to require any of the young actresses to take their tops off onscreen. His first cut was over three and a half hours long, and as Linklater edited, it seemed like the movie wanted to be the shaggy, affable hang-out it became. With accumulated experience and hindsight, Linklater says late in the book that part of his mistake was not to realize that cinema “can’t help but glamorize. . . . It’s a nostalgia creator.”

Compared to American Graffiti, D&C has an intrinsic flaw: it lacks its predecessor’s poignant core. Lucas’s film is set at a 1962 hinge point when its characters are unaware of the social upheavals about to come, and catches them in a last gleaming of petty, horny, obnoxious innocence, until the closing title cards reveal their fates, including a death in Vietnam. Linklater’s story meanwhile is about a post-1960s teenage fecklessness that hadn’t altered much between 1976 and 1993—as a couple of actors note, the 1970s rock of its soundtrack wasn’t far from the 1990s grunge they were used to. (Endearingly, in advance of filming, Linklater sent each of the leads a custom mixtape of what their characters would have listened to.) Of course, more radical changes would come. Part of the reason D&C endures now is that it catches in amber teen life before smartphones, social media, the rise in school shootings, the War on Terror, and climate-change dread. Its characters’ biggest problems are the freshman class’s fear of a brutal hazing and incoming senior Randall “Pink” Floyd not wanting to sign his football coach’s anti-drug pledge. There are vague hints of troubled homes, and of the young women’s annoyance with their treatment by the guys who dominate the film. But a scene illustrating some effects of severe racial segregation—a very real thing in the Huntsville, Texas, of Linklater’s youth, as several classmates testify to Maerz—hit the cutting-room floor. As a pure mood piece, the film is perhaps better for it. But it means all its emotional heft rests on the dumb, heartbreaking, half-hopeful/half-worrying cluelessness of adolescence itself.

In that interest, Dazed and Confused was fortunate in its director, who brought with him the collaborative ethos of Slacker and encouraged his young stars to help shape the material, partly based on the developing off-screen relationships that Maerz juicily describes. Linklater said it would be a failure if all they did was shoot what he’d written. (No wonder he was at war with producers over schedules.) What’s more, unlike most people who make art-house films, Linklater had been a popular athlete and student leader in high school. Yet he was still somewhat an outsider in Huntsville, due to his family’s unstable and peripatetic domestic life, which he eventually fictionalized in Boyhood. This may help explain how he came to straddle indie and mainstream sectors later in his career, but it definitely accounts for D&C’s unusual refusal to play favorites among its teen subcultures. It dislikes the bullying—in fact, Linklater helped put a stop to this “freshmanizing” when he became an upperclassman—but otherwise it’s on everyone’s side, and no one is a mere stereotype. Cool quarterback Pink and weedy freshman Mitch each represent Linklater at different times. Even McConaughey’s creepy but charismatic older-dude Wooderson, who hangs around for drugs and to mack on high school chicks, is permitted the dignity of his hidden sadness and half-baked philosophies. (The director’s weakness for less-than-fully-assed pontificating honors his autodidact background, and your tolerance for it may affect how much you’ll embrace his work.) As later long-term Linklater collaborator Ethan Hawke tells Maerz, “He loves the jocks and loves the geeks, he loves women and men, scientists and space cadets—he relates to them all.” To this day, Linklater considers his skills closer to being a team coach than an autocratic auteur.

Whatever we’re meant to think Pink ultimately decides, Linklater did quit the football team to move in with his dad in Houston, then came back to start college on a baseball scholarship, then was diagnosed with a minor heart condition that ended his sports years for good. He went to work on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, where he saved up the cash that would fund his years of self-taught filmmaking in Austin. Going through all these stages might have helped develop Linklater’s acute sensitivity to the passages of time. The one thing D&C has over American Graffiti is its uncannily vivid feel for the texture of each minute in its day and night of action and inaction. Being so fully in the moment, perhaps it is anti-nostalgic after all.

Indeed, time would become arguably Linklater’s greatest subject, carrying into fiction the power of the late Michael Apted’s longitudinal Up documentary series. His Before trilogy checks in on an improbable couple (Hawke and Julie Delpy) once every nine off-screen years; Boyhood was shot over a twelve-year period while its protagonist (and the actor who plays him) grows up from ages six to eighteen; and now he’s spending two decades shooting the Stephen Sondheim musical Merrily We Roll Along, whose ensemble is older in the first half and younger in the second. In Alright, Alright, Alright we learn that Linklater’s original concept for D&C would have been more like Slacker in how it compressed time: “[ZZ Top’s] Fandango! would be playing and you’d hear the click of the 8-track, and we’d just play the album in real time. We’ll never leave the car. But all this weird shit would be happening in and around the car. And the 8-track would go around a couple of times, so you would hear every song at least twice. That was the movie.”

I confess I’m dying to see that alternate version of Dazed and Confused, though it probably wouldn’t have had the magic of the looser final film, and wouldn’t have served as such an accommodating foundation for a whole tribe of actors, as well as the directors Linklater’s inspired. D&C’s renewal of the coming-of-age form had countless ripples. There is some tut-tutting in the book about whether to blame it for That ’70s Show (the way American Graffiti spawned Happy Days), but I associate D&C more with Freaks and Geeks, which had a similar ecumenical love for its various circles of fuckups, and became the wellspring of the Judd Apatow extended comedic universe. The single-night partyscape model carried on into movies such as Superbad, Adventureland, and Booksmart, and D&C’s presence also can be felt in almost every subsequent stoner movie, not to mention any film that feels built on a mixtape soundtrack (High Fidelity, Guardians of the Galaxy, etc., etc.). A work of art doesn’t need to be perfect to point into new stratospheres. It just might have to be alright in a way nothing’s ever quite been alright before.

Carl Wilson is Slate’s music critic and a freelance writer based in Toronto.