IN “WHAT IT IS I THINK I’M DOING ANYHOW,” written in 1979, Toni Cade Bambara lays bare the bones of her writing life. Short fiction had her heart, she said, having released by then two separate collections, Gorilla, My Love (1972) and The Seabirds Are Still Alive (1977). “The short story makes a modest appeal for attention, slips up on your blind side and wrassles you to the mat before you know what’s grabbed you.” This she found suitable to both her temperament and schedule, completing her work between time as a mother, partner, worker, and community member. “I could narrate the basic outline while driving to the farmer’s market, work out the dialogue while waiting for the airlines to answer the phone, draft a rough sketch of the central scene while overseeing my daughter’s carrot cake, write the first version in the middle of the night, edit while the laundry takes a spin, and make copies while running off some rally flyers.”

Unspooling peripheral to the main or “dominant” narrative event, the short story is ancillary, occurring “in the margins of ‘Life Itself,’” as Elif Batuman wrote in 2006. Gay and lesbian authors and readers have found especially fecund ground within said marginal limits. Attuned to deconstructionist reading, they are well-equipped to counterwrite and interpret history, and doggedly mine obscure, unspoken, and latent material. By nature furtive, propelled by allusive intrigue, the short story is a vehicle for those desiring agents regarded with hostility by the novel, which has typically reflected the conventions of larger, bourgeois society. The action percolating off center stage beckons the reader savvy or hungry enough to search for it. Marginalia, slant and illuminating, can dazzle from the page’s perimeter.

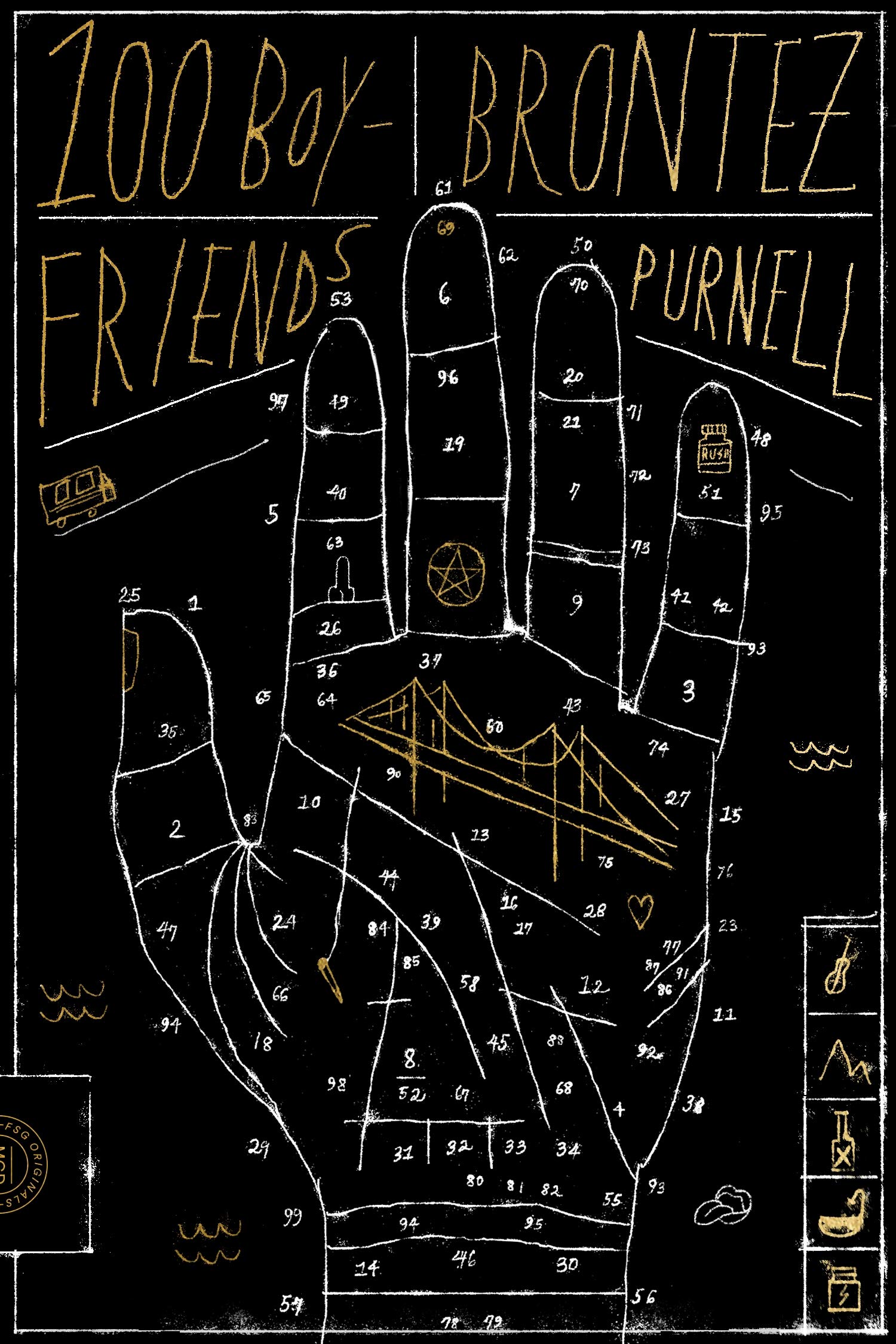

Brontez Purnell’s latest, 100 Boyfriends, is a collection of tales chronicling the knotty intimate lives of queer men and boys in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, the foothills of Appalachia, Rotterdam, and elsewhere. Purnell’s subjects arrive lurchy, neurotic, and frequently unsober, grasping at the edges of themselves and each other. The itinerancy in locale and perspective, well suited to the fragmentary form, also finds a natural complement in Purnell’s spry humorizing and keen modulation of rhythm and pacing, skills no doubt sharpened by his history as a musician. Born in Triana, Alabama, Purnell, a longtime Oakland resident, has played in the bands Gravy Train!!!!, an electroclash classic, and the Younger Lovers, practitioners of melodious garage punk. He’s also a zinester, responsible for the cult favorite Fag School, and a dancer-choreographer who founded his own experimental-dance company. In 2018, he won a Whiting Award, having authored several works of fiction, including his debut novel Since I Laid My Burden Down (2017).

Amid all the perambulating of 100 Boyfriends, there are certain perennials, familiar and bright: bathhouses, gyms, amore and battle done in the school bus’s rear. One boyfriend, unmoored following a row with another, thusly summarizes the psychic landscape: “He couldn’t characterize all the dysfunction exactly, but he could calculate that it was a mix of compulsion, exclusion, obsessiveness, jealousy, infidelity, always wanting to ‘outsmart’ each other, and, amid all of this, an extreme sense of separation anxiety.” Purnell provides a taxonomy of each city’s legion lonely and their disparate, gentrifying haunts, a history of people and their places.

There is ample time spent in bathrooms, spaces that are paradoxically communal and private, universal and singular, sterile and scatological. The public restroom, a modern invention designed to neatly manage the human body and its excretive material, has instead become the locus of modern cultural-political anxieties surrounding race, hygiene, sex, and sexuality. Purnell recalls its history as a site of homoerotic desire. The story “Letter of Resignation” opens with a restless, insatiable nonprofit employee’s bald confession: “I am fucking my coworker’s husband.” Encounters between the two often take place in a downtown mall, inside of a mucky, eighth-floor latrine, which has figured in the protagonist’s sexual life for years. The nondescript stall corresponds to a similar, vacuous indiscernibility stalking the narrator, a “clinical sex addict” who spends part of his days masturbating unnoticed in his office cubicle. He smears semen into the craggy carpets, broaching with frequency and ease the barriers that delineate bodies and space, labor and pleasure. At a glance, he resembles Jean Genet’s epic masturbator, the solitary act intended to ward off a terrible, inexorable loneliness—showing up hot-blooded and fiendish in Genet’s subject, cool and limpid in Purnell’s—but reifying it instead. Of his desire to lose himself in a “nameless void of men,” the narrator muses, “Sex is just light points on a grid, stars in the Milky Way, but really, the ether holding them all together is the waiting. Just sitting around, waiting in some feces-scented bathroom hoping to get fucked.”

Raised Christian, Purnell is duly fixated on the corporeal, blood and bodies in all their seeping, unruly acridity. “Let this contorted, flickering, screaming body speak,” wrote Hervé Guibert, who pioneered French autofiction in a spew of “eructations, defecations, ejaculate from jerking off, diarrhea, phlegm, oral and anal catarrhs of the mouth and ass.” “I would see if Hercules was waiting,” writes Purnell. “If so I would be his snack tonight and take my antibiotics again in the morning.” The matter of cruising is central—waiting, seeking occasional shared gratification. “I called them ‘boyfriends,’ though this was not always the case,” the narrator of “Mountain Boys,” says. “But they were all like pieces of bubblegum you chew hours after the flavor leaves and that you accidentally swallow, and then (supposedly) sit in your guts for seven years.”

The collection recalls, in style and substance, the New Narrative of the late 1970s and ’80s, when the burgeoning influence of HIV/AIDS awareness amid the sexual revolution invited gay literature out from underground, from short stories in Playboy, wanted ads in newspapers, and other snippets. More recently, theory seems to have become the dominant influence on queer writing, producing pristine, aquiline prose, glass sharp, and long, long, long, with references strung together like rosary beads. Many of Purnell’s characters wrestle with the tension between assimilation (and its associated comforts) and feral roving, the search for meth, raves, poppers, and satanic sex by the bay. None are angling for husbands, let alone children, amassing instead a coterie of roommates, lovers, boyfriends. But the imprint of the family, foundational site of queer trauma, marks all relations made otherwise—dead fathers continue to haunt, abandoning mothers impart a lonesomeness that sticks. Another boyfriend: “Figuratively speaking I don’t have a mother, a last name, or a goal or purpose in life. I’m just a hole.”

These are Black stories by a Black queer author of great prolificity and range, but traffic in no BLACKNESS™ legible to the consumptive masses seeking antiracist reading lists. They are about race in the way that everything is about race, but they are also performances of technical virtuosity, formal experimentation, and mastery rarely acknowledged in Black writers, whose primary function—that of teacher—is presumed to be at the level of content, not style. They play with and resist autobiography, enlivened by Purnell’s marvelous ear for Black vernacular and his finely meted candor. The stories end as they begin, without clear resolution or arc, slipping out quietly into the morning light.

Jasmine Sanders is a writer from the South Side of Chicago.