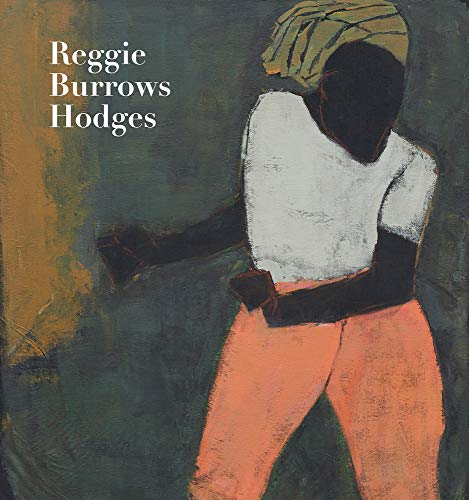

BROAD SWATHS OF VARIEGATED COLOR animate Reggie Burrows Hodges’s canvases at least as much as his energetic subjects: unicyclists and hurdlers; basketball, tennis, and baseball players. Born in Compton, California, he attended the University of Kansas on a tennis scholarship and studied theater and film; while living in New York and Vermont, he wrote songs and performed with a dub-rock group. The fifty-six-year-old artist’s résumé helps explain his fascination with sports as well as several paintings of people spinning and listening to dub records. In this volume’s interview with Suzette McAvoy, current Maine resident Hodges cites fellow Mainer Marsden Hartley as an influence, along with Winslow Homer and Alex Katz—all painters who employed color boldly and with a sense of narrative intensity. But even in active scenes that suggest more buoyant emotions, Hodges’s rich palette conveys a brooding sense of meditative stillness.

According to Hilton Als’s elegantly informative essay, Hodges begins by painting the entire canvas black. The hues he then applies seem to flow across this field in ways directed but not controlled, achieving an effect that calls to mind Helen Frankenthaler’s soak-stain technique. In Hurdling: Sky Blue, 2020, a runner is poised in midair, leaping over one of a series of bars. From an improbable vantage directly in front of the figure, Hodges depicts the stanchions with an increasingly vivid orange so they appear as illuminated steps. Behind the runner, the sky is a wash of blue-tinged pink. As is the case for all of Hodges’s figures, the subject’s face is rendered in nearly featureless black. Subtle reverberations between the colors, their varying densities and relations to light, generate a lush yet pacific atmosphere. Instead of charging furiously toward us, the runner levitates gracefully on a celestial staircase.

Less otherworldly but equally complex is Hodges’s depiction of a dancing woman in Community Concern, 2020. Again, the figure is engaged in presumably strenuous activity, but the blocks of color—her white shirt, fiery orange slacks, and the sea-green background—convey a solidity that is somehow heightened by the black paint that articulates, with an almost geometric angularity, her arms and face. The woman moves but doesn’t—or rather she appears to be on the verge of moving. She occupies an imminent moment, one in which her self-possession soothes rather than stirs. The absence of a readily legible facial expression connotes an inwardness at odds with the thrumming music she must be hearing, as well as the lively company of other dancers—the title invokes a community we sense but don’t see. In the interview, Hodges describes music as “a major driving force” in his life and identity. “It’s a medicine,” he says. “A solution for acclimating myself and situating myself within a space.” Many of his figures are kinetic—they cycle, dance, and leap, the power of their motion radiantly self-evident. But Hodges’s poetic understanding of color situates them in their space, revealing in each a concentrated and reflective presence.