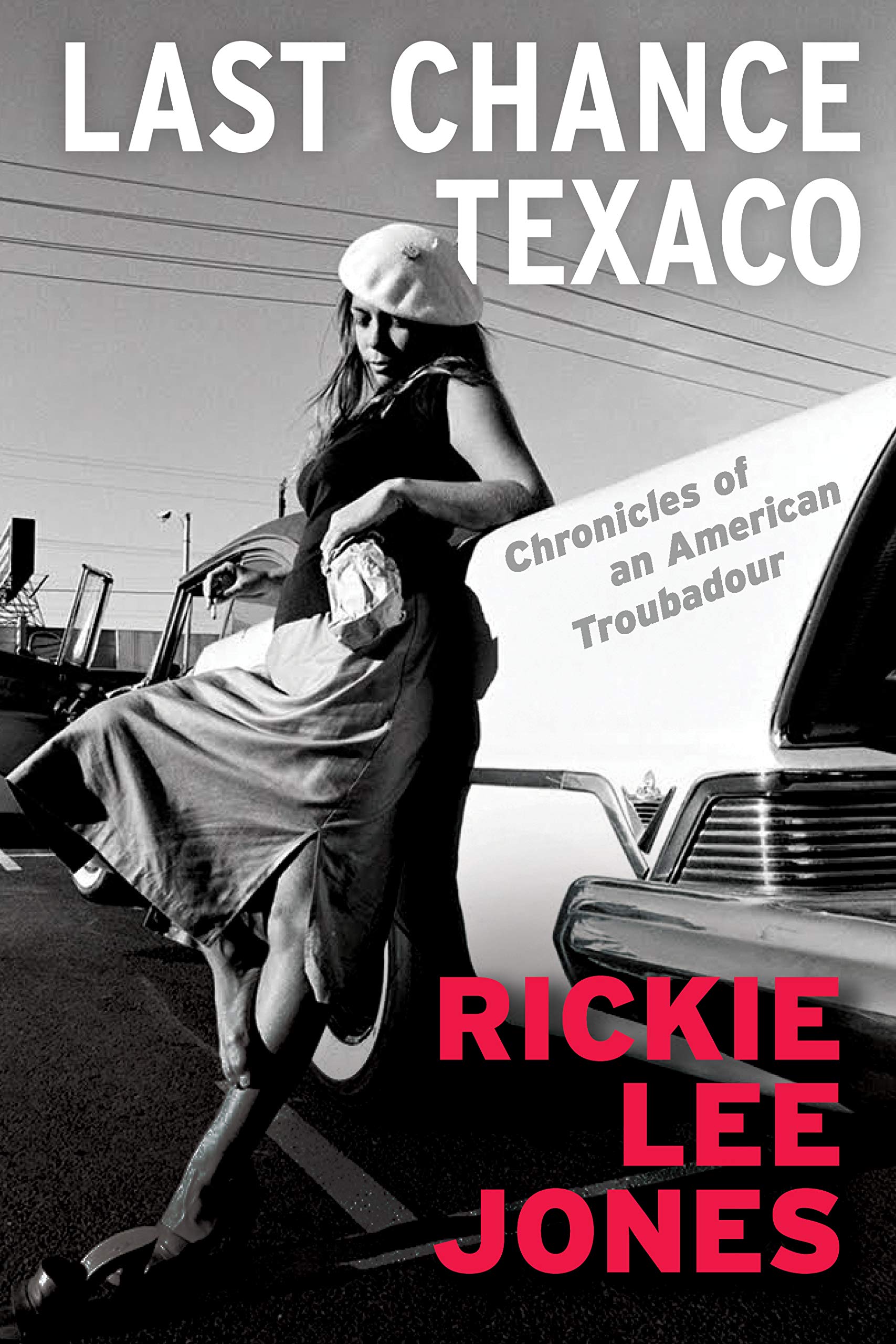

RICKIE LEE JONES’S BLOND HEAD IS ATILT as she lights a French cigarette, crowned with an off-center red beret. It’s that image of the artful-dodger “duchess of coolsville” (as Time dubbed her) on the cover of her eponymous 1979 debut that became iconic to a public who still recalls her mainly for that year’s jazzy top-10 single “Chuck E’s in Love.” It was a sell, but one close to the reality of this former teen street kid and, more recently, poverty-line Venice Beach bohemian. Jones rejected the 1970s “glamour-puss” gloss that was being urged on her and brought her own wardrobe and sensibility to photo shoots. She knew the story she wanted her pictures to tell.

As Jones relates in her new memoir, Last Chance Texaco: Chronicles of an American Troubadour (Grove Press, $28), she realized what the pose echoed only later. In a 1920s publicity shot, her grandfather, Frank “Peg Leg” Jones, leans forward in a cocked straw boater, also sparking up a smoke. Frank had been a star singer and dancer on the vaudeville circuit, once billed above Milton Berle. He’d lost a limb in a childhood train-track incident, and one reviewer wrote, “This mono-ped puts most two-legged men to shame.” (His condition also foreshadowed the motorcycle accident that would cost Rickie Lee’s older brother Danny a leg and a traumatic brain injury, and her whole family the scant cohesion it had up until then.) Along with musical talent, Peg Leg seemed to pass down to the granddaughter he never met a knack for improvisation, an itinerant vaudevillian’s ability to make something unexpected out of stray chances.

Those who think of Rickie Lee Jones as a late-’70s one-hitter may not grasp how far that gift went. Signed in a major-label bidding war after writing only a handful of songs, Jones recorded her first two albums with a who’s-who of top SoCal session musicians. Warner Bros. hyped her with a pseudo-boho promo film that might count as the first major US music video, sending record stores across the nation VCRs and monitors so they could play it. It helped her score a Saturday Night Live spot the week her album was released, two Rolling Stone covers in quick succession, and a Grammy as Best New Artist. Her second album, Pirates, willfully hit-free, was instantly acclaimed and still appears in canonical album lists today, including mine.

Into 1984’s The Magazine, Jones established a voice soaked in Billie Holiday and Betty Carter, doo-wop, Laura Nyro, and Astral Weeks–era Van Morrison (with whom Jones has a fraught run-in in Ireland late in the book). Her music was peopled with characters drawn from her peripatetic life, the sprawling cast of a raunchier West Side Story—a soundtrack she often bonded over with fellow travelers. Her songs slipped registers from street slang to emotional metaphysics, with structures often more like modular suites than pop tunes, and swirls of vocal harmonies.

Ripples of her sound run through the pool of 1990s singer-songwriters, from Sheryl Crow to Alanis Morissette to Tori Amos. But that was rarely spoken of, partly due to the micro-generational antagonism between Jones and Joni Mitchell, who mutually resented their sexist press comparisons as pretty blond singer-songwriters, despite common ground as jazz-minded visionaries. Acknowledging big-sister Rickie, for the Lilith Fair cohort, skirted betrayal of godmother Joni. But Jones also lost her clear compass and scope for a while after her 1980s peak. The novelty notoriety of “Chuck E” cast a shade, leaving listeners unprepared for her tangents. Yet she also had a penchant for self-sabotage that Last Chance Texaco finally illuminates, though thankfully never explains away with pat pop psych. It takes in history, class, and family.

Peg Leg Jones left his descendants not only a musical inheritance but a violent, drunken one. Rickie Lee’s father, an aspiring actor and singer himself, fled that environment as a teen during the Depression, got post-traumatic stress in World War II, and didn’t shake his restlessness, hard drinking, and volatile temper until late in life. Meanwhile, Rickie Lee’s mother Bettye was snatched by social workers from her young single mother and grew up mostly in midwestern orphanages (as told in her daughter’s song “Night Train”). Once out, a distrustful Bettye was prone to cut and run, from Chicago and around Arizona, California, and Washington State, repeatedly unsettling her family in pursuit of something better, or something else. She hid from affection, too.

Jones’s book is much less about her musical career than it is a reflection on this legacy of mid-twentieth-century American dispossession. Its first two-thirds reads almost like a novel about a lower-class family and its wayward daughter, a southwestern version of Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, except that Jones romanticizes her forebears and is loathe to frame her upbringing as abusive, no matter how harrowing it got. Her recollections are as vividly cinematic as her best lyrics, with the same heightened conversational rhythms. As in many of her songs, stories tend to resolve via an agnostic mysticism, an “invisible world” somehow watching out for her.

This reflexive optimism is a mark of white baby-boomer music and writing—there are threads in common with Bruce Springsteen’s own recent memoir, though without the biblical, masculine, and arena-scale rhetoric. Jones’s stubborn hopefulness helps rationalize how the at-risk girl readers meet here is somehow alive, well, and relatively contentedly living in New Orleans at sixty-six. One fears for her life so often after she starts running away, along the hippie trail, in her very early teens, the first time with a boy in a stolen car. Later come skirmishes with gangsters, would-be abductors, abusive boyfriends, and even a putative “pimp with a heart of gold” in LA.

Sudden pop success did little to suppress the Jones-clan flight response. First she chased it through heroin, a vice picked up from musician’s musician Dr. John, aka Mac Rebennack (with whom she, spitelessly, continued collaborating nearly up to his death in 2019). Potent addiction poetry is laced through both Pirates and The Magazine. Jones’s habit lasted only a few years, but crucial ones, and the resulting “hard to handle” stigma helped forfeit her the kind of production support her work merited. It may have served, even partly been intended, to fend off commercial pressure, but her erraticness left only cult loyalists to sustain her.

Within that cult, there was another toxin in circulation, which I admit is where I come in. For a segment of Jones’s listenership in the early 1980s, her story was wrapped up in the lore of her romance with Tom Waits and the scene around the Tropicana Motel in Hollywood, where they hung with hipster hanger-on Chuck E Weiss (the “Chuck E” of her hit), and lived large in dissolute boho style. The Peg Leg stories Jones told then in interviews seemed untrustworthy to me by association with Waits’s more obvious jive patter and prevarication. Last Chance Texaco makes it clear that she was the one who came by all that color honestly, while the much more middle-class Waits inhabited a character out of secondhand tales of beatnik glory. (Even in bed, she writes, he was “never not performing,” like a circus lion.) During their entanglement, Waits began shifting out of his retro shtick, but she got no thanks for that, while the jazz-throwback side she’d drawn from her dad was unfairly credited to Tom. As she writes here, “I remain the unseen image at the Last Supper. Was I there? Scholars disagree.”

Their boozy Romeo and Juliet playlet was unlike any other pop-romance template of the time, and as Jones writes, “Our disciples rippled out into the world—followers. You can still see them today.” I’ll confess my high-school girlfriend and I were among those acolytes, affecting the beret and the fedora, poring over lyrics for secret messages. Adolescents plunder whatever self-fashioning they need, as I try to remember when I’m impatient with online pop “stans” obsessing over backstage gossip today. But post-separation the burden fell exclusively to Jones, as the woman. Waits was so quick to reinvent himself as a 1980s avant-gardist—a class privilege, too—that he outright refused having any past to address. The imbalance between their statures remains an injustice. In Last Chance Texaco, Jones finally narrates the story in full, reluctantly answering to nostalgic voyeurs like me. She’s said it was the hardest and most healing part to write, which she had to revise and revise in order to purge the bitterness. She succeeded. It’s sexy and moving and sad. And I hope she never has to talk about it again.

The book wraps up quite perfunctorily after those intense rise-and-fall years, barely glancing at her subsequent marriage, parenthood, and later albums (many of them strong on their own, altered terms). This rescues the book from the third-act problem of many celebrity memoirs, when the “becoming” saga ends and the “being” grind begins. Its mission seems complete once it’s finished confronting the early baggage of that girl in the red beret. With luck, Last Chance Texaco may prompt a wider reevaluation of the biases critic Hilton Als exemplified in Bomb magazine in 1997 when he wrote, “Ideologically, I was opposed to Ms. Jones, or rather, to her audiences: weepy white women wearing berets trying to approximate, in their speaking voices, black syntax by way of Tom Waits.” After hearing her then-new, exploratory, trip-hop-inflected album Ghostyhead, he had a change of heart: “She could not have recorded this album,” he wrote, “without having given something up and survived it, with wit.” He’s been an advocate ever since.

No doubt Jones has more left to tell. The song “Wild Girl,” from her 2009 record Balm in Gilead, would sound initially to any reader of this book like a love letter to her younger self, but it pivots midway into a fretful birthday song to her own daughter Charlotte. It joins other discreet hints over the years that Peg Leg Jones’s dark bequests may have carried into another generation. A memoir may not have been the place for Jones to contemplate that, but often this kind of retrospective exercise can help renew an artist’s overall energies and, vitally, a reciprocal response among listeners. As she sang in perhaps her greatest single song, Pirates’ “We Belong Together”: “The only heroes we’ve got left are written right before us / And the only angel who sees us now / Watches through each other’s eyes.”

Carl Wilson is the author of Let’s Talk about Love: A Journey to the End of Taste (Continuum, 2007).