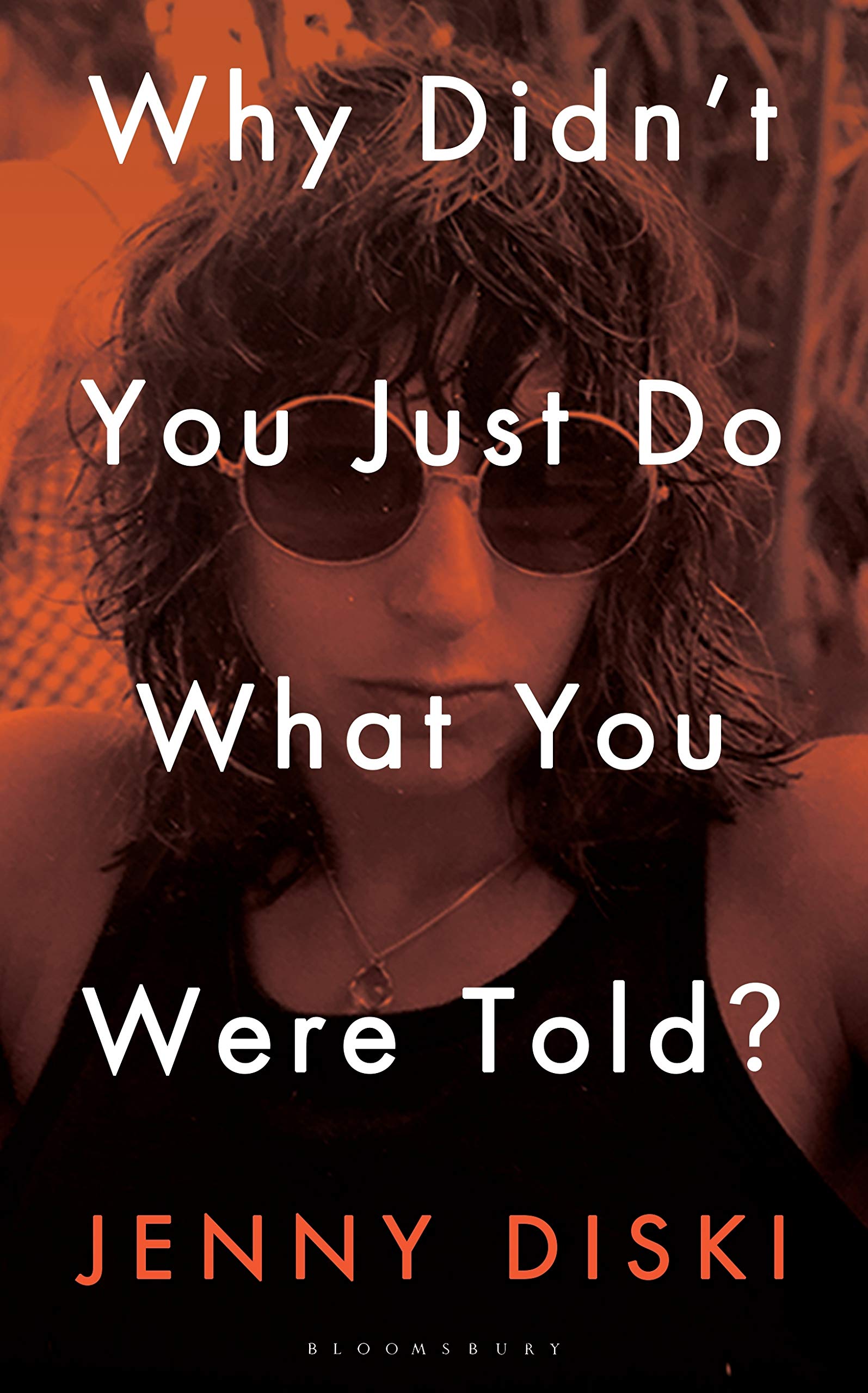

FOR NEGATIVE LESSONS, the “don’ts” when it comes to writing reviews, there’s always the internet. But for direction and inspiration, cold water on a face flushed from a looming deadline, it’s better to have hard copies of whatever you think defines greatness: you can open one to a random page, like shaking a Magic 8 Ball, and ask it what to do. Jenny Diski’s new, posthumous collection, Why Didn’t You Just Do What You Were Told?, might give an answer—ultimately, obliquely—to its own title’s question. Of course it can’t answer mine. But I’m sure I’ll periodically give it a try anyway, because, while devoid of encouragement or advice or a style that anyone could imitate, its thirty-three pieces—essays, book reviews, and “book reviews,” written for the London Review of Books between 1992 and 2014 (selected from the roughly two hundred that the magazine published)—still impart a strange sense of possibility.

They tantalize, in a bleak way, with the suggestion that invention might arise from inertia and depression as much as, or more than, from creativity (whatever that is) or hope. “Indolence has always been my most essential quality,” Diski observes. “I cannot recollect a time when the idea of going for a walk was not a torment to me; a proposition that endangered my constant wish to stay where I was.” It seems she harnessed the force of gravity rather than combustion to produce ten novels and a book of short stories in addition to a daunting amount of nonfiction during her life. This volume, which is so impressive for its odd turns and bright torpor, reminds me that walking is actually just falling forward. Maybe writing—a worse torment—could be something like that too.

On subjects as diverse as arsenic poisoning and office supplies, Nietzsche’s little sister and Freud’s wife, Piers Morgan’s diary as well as Anne Frank’s, Diski dispenses with conventional structures for her reviews, favoring digression above almost all else. A book could be no more than a starting point for her text—or maybe it’s just sometimes hard to figure out how closely her discussion relates to the literary effort in question; she didn’t feel a duty to refer back to it constantly. In the end, a review might read more as an adjacent rumination on a given topic—or it might tip into memoir. Her tenure at the LRB in fact began with the personal essay “Moving Day,” a meditation on the post-breakup rapture of reclaimed domestic solitude. She describes “the splitting-off of a protoplasmic self that insinuates itself into every part of the flat. Like smoke, it wisps into corners and under sofas.” In this paradise, the hallowed seclusion and spare rhythm of her writing days “won’t be broken by people coming in from the outside world with their own stories and their own internal speed.”

Diski’s prose is quick-witted but not fast-paced. She was less about the bon mot than a cumulative, unfolding, ironic wit—a self-aware, sage pessimism detailed in cool, very long paragraphs. Blocks of unbroken text span pages, each for its own reason, but all contributing to an appealing air of tenacity and excess. LRB editor and friend Mary-Kay Wilmers allotted Diski whatever space she needed for her long-form pieces, encouraging the author’s unique sense of proportion. Her 2000 review of Tom Bower’s unflattering biography of rakish Virgin Group magnate Richard Branson is expansive, to say the least. If you’re accustomed to handing in reviews at about one-third (or at less than one-tenth) the length, you’ll find plenty to slash—whole swaths in a single stroke—plus sentences and clauses to trim, easily shrinking her paragraphs down to a reasonable size. But that would be a shame, and make “Stinking Rich,” as her review of Branson is called, a different thing. Given ample space, Diski was able to put Branson in colorful context, as a late-twentieth-century forerunner to the now-familiar figure of the false renegade, the populist billionaire peddling an antiestablishment brand alongside whatever else he has for sale. (“I find myself nostalgic for the time, long ago, when one thing the very rich and very famous could be relied on to do was shut up,” she starts off.) She also had space to try on—and see through to the end—the half-satirical pose of siding with the high-profile entrepreneur against his sanctimonious, superficial biographer.

Branson, playing “buccaneer and victim” all the way to the bank, may be a fraud, but Diski confesses a “guilty sympathy” for frauds, the “hounded wrongdoer” on television exposés. “What do you expect?” she asks. “They were only doing their job, making money by making promises. Why are you asking them why they did it?” Her point is that Branson is a late-capitalist celebrity-culture inevitability, and therefore not entirely at fault for his contemptible role. Bower, on the other hand, is totally at fault for failing to reveal something about Branson that Diski didn’t already know.

With her own writing, she set a high bar for psychological depth. In her flooring 1997 memoir essay “A Feeling for Ice”—the collection’s keystone, I think—her identification with torpor (and perhaps with the hounded wrongdoer, too) comes into focus. She slips like a ghost through walls, keeping a hold on the zigzagging threads of her story while merging—through understated, unannounced abutments of sentences or paragraphs—a longed-for trip to Antarctica and a more perilous journey into her past. Setting up the visual terms of the piece, she writes, “I wanted white and ice as far as the eye could see, and I wanted it in the one place in the world which was uninhabited. I wanted my white bedroom extended beyond reason.” She traces the craving for panoramic blankness back to her experience in a psychiatric hospital at age fourteen, following a Nembutal overdose. The institution’s crisp sheets became an enduring symbol of an out-of-reach ideal: oblivion. (Diski, whose parents were both deemed unfit, was released to a schoolmate’s mother, the author Doris Lessing, whom she lived with in London until she was nineteen.)

In a tone of dissociative understatement, Diski uses a conversation, over tea, with the elders of Paramount Court, the block of flats where she grew up, to prompt and flesh out her memories of dangerously dysfunctional parents: the fights, the sexual abuse, and their own attempts at killing themselves. (It’s a bracing matter-of-factness that surfaces elsewhere in Diski’s writing.) When the concerned Mrs. Rosen, one of her neighbors from decades ago, asks the writer if her father—who Diski has just found out was a professional con artist—beat her, she replies that both parents slapped her face, “but it wasn’t a big thing. Nothing special.” The essay shifts, without skipping a beat, to passenger protocol on her voyage to Antarctica: “The rules. One hand for the ship applied at all times: always keep a hand free to hang on to safety rails, inside and on deck. Get to meals on time.”

A hand slapping a face, a hand holding a rail for safety—the synaptic immediacy of Diski’s stark imagery is even more powerful than the steadily unfurling metaphor of the frigid expedition in “A Feeling for Ice,” which is saying a lot. Years later, in 2014, when she wrote about Barbara Taylor’s The Last Asylum: A Memoir of Madness in Our Times, Diski again drew on her teenage experiences in what both she and Taylor refer to as the “bins.” Here, Diski’s autobiographical material is not organized according to the dream logic of “A Feeling for Ice.” It’s instead shaped by her agitated engagement with Taylor’s book, which takes readers on another novel kind of trip. The review is Diski’s most “positive” take in the collection. She praises Taylor’s convincing depictions, vouching for the book’s historical and artistic credibility by offering her own memories. “This, then is not even a pretence at a neutral, objective review,” Diski admits (or boasts).

When she elaborates on this disclaimer later in the essay, she gives voice to what was perhaps a perennial struggle, a problem that doubled as her elemental strength as a critic. “Despite my intermittent insight,” she explains, “it was impossible to get through Taylor’s singular and carefully structured account . . . without my childish, intrusive self chattering a comparative commentary.” In transcribing that chatter, here and in general, Diski wound up with prose compelling for its air of choiceless surrender—her writing always seems to take a hapless preordained form, which she frames as a kind of affliction—but this effect is, in truth, a result of her formidable control. Her polish gives it away.

“Indolent” is a funny way to characterize her natural state, which seems more like “incisive” to me, but I also have the unshakable sense—for myself—that writing can’t or shouldn’t look like staring into space or feel like not wanting to move from the couch. “A fraud is being perpetrated: writing is not work, it’s doing nothing,” she states in that first essay, from 1992. But she immediately counters with, “It’s not a fraud: doing nothing is what I have to do to live.” Listing a few more pertinent existential options, Diski ends with, “Or: writing is what I have to do to be my melancholy self.” The protoplasmic, chattering, melancholic “I” of these essays is, of course, the collection’s constant, its true subject. I can commiserate with her on every page even if emulation is out of reach.

The final essay included here, “A Diagnosis,” from 2014, details the oncology ap-pointment during which she learns of an inoperable, malignant mass in her lung; she died in 2016. “In my experience, writing doesn’t get easier the more you do it,” she shares, reflecting on how she’ll spend her last days, working on a new book. “But there is a growth of confidence, not much, but a nugget, like a pearl,” she continues, adding, lest her statement come off as the kind of pep talk I’m always hoping to find, “like a tumour.”

Johanna Fateman is a writer, art critic, and owner of Seagull Salon in New York.