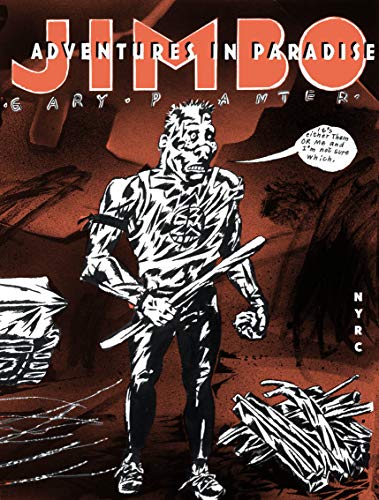

GARY PANTER’S COMIC STRIPS ARE FUN TO LOOK AT AND HARD TO READ. “My work,” he’s admitted, is “not very communicative.” Panter made his mark as a poster artist in the late-’70s Los Angeles punk scene, established his reputation in the ’80s as a frequent contributor to Raw magazine, and confirmed his cultural bona fides as a designer for Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise, originally published in 1988, draws on a decade’s worth of work for Raw and the punk tabloid Slash; it now reappears framed by a brief Ed Ruscha appreciation (dig “the ravings and cravings of an amped up active mind”) and Nicole Rudick’s contextualizing afterword. The material is organized to create a quasi-narrative abstract action-adventure starring Panter’s recurring character Jimbo, a punk icon suggesting a bulked up, snub-nosed, post-shock-therapy burn-out mutation of the eternal high school student Archie Andrews. (One of the great things about Panter is how other cartoon characters surface, bent out of shape, in his world. Jimbo meets Nancy, and a Picassoid Fred Flintstone appears in another subplot.)

A master of the expressive chicken scratch—as evocative of the punk era as “fuzzy three-chord loud songs,” per art historian John Carlin—Panter views his work more in terms of “marks” than lines. Still, his drawing is superb and his sense of composition impeccable, as demonstrated in the boldly mismatched full-page illustrations that end Jimbo’s adventure with his failure to disarm an atomic bomb. Far from primitive, Panter absorbed quite a bit as an art student at East Texas State University.

In a general sense, Panter serves up cartoon iconography in a jagged cubist space amplified by punk aggression. His sophisticated list of influences include Jean Dubuffet, Jack Kirby, David Hockney, Peter Saul, Oyvind Fahlström, ’60s rock posters, and the Hairy Who. (As analogues I’d add Cy Twombly’s half-obliterated calligraphy and Bill Holman’s cacophonous screwball strip Smokey Stover.) Rudick mentions Robert Smithson’s visit to East Texas State and speculates that Panter might have been impressed with Smithson’s notion of a blended Jurassic and far-future landscape. Bottom line though: Panter’s drawing is utterly distinctive.

Indeed, given the quality of his graphic work (not to mention his posters, performances, paintings, and Pee-wee’s Playhouse designs), Panter is long overdue for a career museum retro. Perhaps Panter: Entering the Pantheon will be prompted by this classy new edition of Jimbo: Adventures in Paradise.