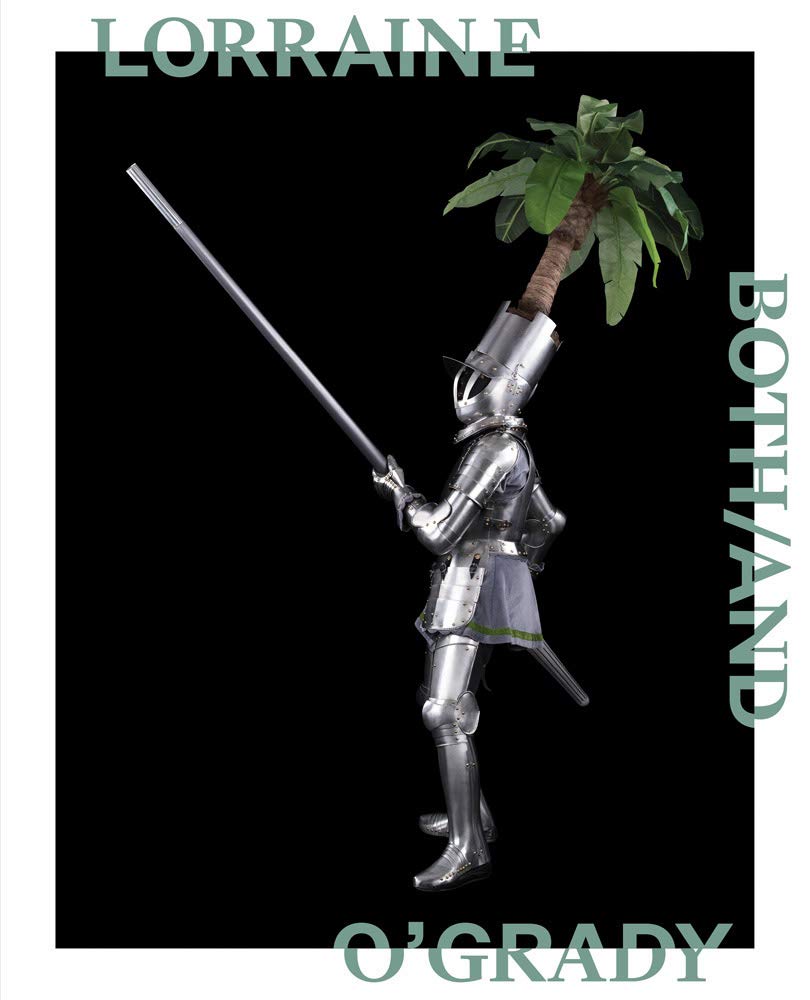

FOR OVER FORTY YEARS, Lorraine O’Grady’s work has argued against binary thinking. Instead of either/or, she proposes a both/and construction, often expressed by pairing two images in a diptych. Take her 2010 Whitney Biennial work The First and the Last of the Modernists, in which she juxtaposes portraits of Charles Baudelaire with Michael Jackson, tinting them in red, gray, green, or blue. As she wrote in 2018, “When you put two things that are related and yet totally dissimilar in a position of equality on the wall . . . they set up a conversation that is never-ending.”

This sensibility informs the many other couplings in her practice: performance and installation, Blackness and whiteness, the diasporic straddling of origin and destination, visual art and writing. Writing in Space, 1973–2019 is the first collection of the artist’s work in this medium, published in advance of the long-overdue first retrospective that opened at the Brooklyn Museum this spring. The book is astonishing for O’Grady’s way with words alone. We see how she refines her own artist biographies and the framing of her process over time. Her performance scripts are so richly detailed that they read like closet dramas. She describes working as an analyst during the 1960s Cuban missile crisis: “Language had melted into a gelatinous pool. It had collapsed for me.” She says some white rock music “looks like pastry in the window, but when you bite into it, you wonder if they were copying pastry from photographs.” She also manages to turn me on to the Allman Brothers Band in a stunning piece about listening to them through a breakup; I do the same with no small wonder at a distance of several decades and thousands of miles.

While known for her visual work and performances—she describes the latter as “writing in space,” and describes performances as novels—O’Grady came to art through writing, following her stint as an intelligence analyst, as well as a would-be novelist, the head of a translation agency, and a rock critic. She taught at the School of Visual Arts in New York before making her first visual works in 1977, a series of found poetry made by cutting up the New York Times. These were worlds in which one could succeed through merit alone. As she writes in 2012, “I often say that I was ‘post-black’ before I was ‘black.’” The segregated 1980s art world was a rude awakening. She recounts how, in 1980, when she volunteered to do press for the Black avant-garde gallery Just Above Midtown’s inaugural show in a new space, she confidently called the New Yorker to get the show listed. When she told them the name of the exhibition, “Outlaw Aesthetics,” the “Goings On About Town” editor replied, “Oh, they always put titles on shows there, don’t they.” O’Grady adds, “That was the moment I was transformed from post-black into black.”

In Writing in Space, O’Grady recalls that her first public art work, a guerrilla performance as her alter ego, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, at the JAM opening, marked that transformation from post-Black to Black. A beauty queen from French Guiana, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire wore a white gown appliquéd with thrifted white gloves and carried a cat-o’-nine-tails. As she explained in a 1995 interview, “The cat-o’-nine-tails was the whip that made plantations move. It was a sign of external oppression, and the gloves were a symbol of internal repression, internalization of those oppressive values.” She joked with the crowd before declaiming her adaptation of the great Négritude poet Léon-Gontran Damas’s “Enough.” Mlle Bourgeoise Noire used the poem—with her own additions—to decry the passivity and sycophancy of the Black art she saw around her, ending with the exhortation that “Black art must take more risks!”

In her appearances, and as a curator, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire did more than disrupt the status quo. Her hit-and-run performances laid out what the situation was. The visionary 1983 The Black and White Show she curated, which featured fourteen white and fourteen Black artists (including Adrian Piper, Keith Haring, and Nancy Spero), showed who the artists were; and her joyous 1983 Harlem African American Day Parade float performance Art Is . . . framed who the audience should be quite literally—they were photographed with oversized gold frames held in front of their faces. At the time, parade-goers understood that they were the art, too: “Everywhere there were shouts of: ‘That’s right. That’s what art is. WE’re the art!’ ” she remembers. O’Grady understood that she had to create not only the work but also the audience and the theoretical grounds for its engagement. In a 1983 performance statement, she says,

Right now, my goal is to discover and create the true audience, and something tells me that, for a black performance artist of my ilk, this will take a many-sided approach. Because I sense that the true audience may be coming, not here now, I try to document my work as carefully as I can.

And in a 1990 letter to Lucy R. Lippard, she succinctly writes, “The battle I face in the white artworld as an artist and critic is the same as it ever was: to have black genius accepted without condescension.” In Writing in Space, O’Grady has a wide-ranging conversation with Juliana Huxtable in which she suggests that “basically, the struggle may never be finally won, or at least not in our lifetimes.” O’Grady has such control over her texts and their dissemination that the easy, bantering looseness of this and other conversations here is all the more delightful in contrast to the tight precision of her writing.

There’s some unfinished diasporic business, too. In a conversation with artist Catherine Lord in the catalogue for the Brooklyn Museum show, Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And, O’Grady relates how “it was difficult, even in the New York art world, to mention a connection to the Caribbean without feeling as if I were somehow claiming superiority.” And, “in the American context, I always just use the word Black. In the future, though, if I am theorizing myself, I might call myself double-diasporan.”

O’Grady was also rightly suspicious of the white art world’s habit of anointing one or two exceptions-to-the-rule Black stars at a time, noting that “‘peripheral’ art can only be absorbed into the market when the politics of that market’s values allow for its recognition. Hegemonic artists and critics have first to create the appropriate references and spaces for it.” O’Grady, of course, had to do it for herself, resulting in watershed essays like “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity” (1992/1994), included in Writing in Space, which stresses “the need to establish our subjectivity in preface to theorizing our view of the world.” A number of other pieces are illuminating in their erudition—one on Baudelaire and Jeanne Duval and another on Flannery O’Connor particularly impress—and for O’Grady’s pleasingly bombastic habit of inserting herself and her work into the picture to insist on both her subjectivity and her own accomplishments. She knew, even if the rest of the art world didn’t.

In a 2012 lecture delivered at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, O’Grady remarks that in the 1980s and ’90s, the theorizing of white feminism was “one last cruel obstacle to overcome.” The talk examines the ways in which the rise of postmodernism was inextricably tied to whiteness:

I spent all of the 1980s and the 1990s feeling, “God, will it never end? Will they never stop taking up all the room, stop speaking for themselves as though speaking for everyone?” The death of the author? The total construction of subjectivity? Sexual liberation as a prime victory of feminism? For you, perhaps. But for others, there was more.

White feminism today may well have given way to a more varicolored liberal feminism, but the same totalizing dynamics remain. In Writing in Space and Both/And, there is a conspicuous effort to make O’Grady’s work legible. In the former, headnotes and suggestions for further reading by Aruna D’Souza make the volume seem a little bit like Fodor’s the Complete Guide to Lorraine O’Grady. Both/And feels closer to a recuperation project than an exploration of new theories and new forms, even as some of the essays reach into O’Grady’s oeuvre as if it were a packet of Fun Dip, creating crackly sparks with the new connections they forge.

Overall, one marvels at how easily Black female subjectivity is dispensed with, even after all this time, as O’Grady’s body of work is quantized and squared within a singularly white canon. This is especially evident in co-curator Catherine Morris’s essay, which seems to do what a younger O’Grady might have hoped for, writing her into the mainstream by locating O’Grady’s successes in white art—its grounding in Dada, its deployment of Conceptual art strategies—instead of in the entirety of O’Grady’s lived experience. And so, we end up with another either/or. I think of O’Grady telling Huxtable that it’s “really not about being good enough but needed enough.” As she writes in a 2012 essay, “Ah, recuperation. It’s so boring. . . . We must try to be analytic with our recuperation.”

Rahel Aima is a writer and editor based in Dubai.