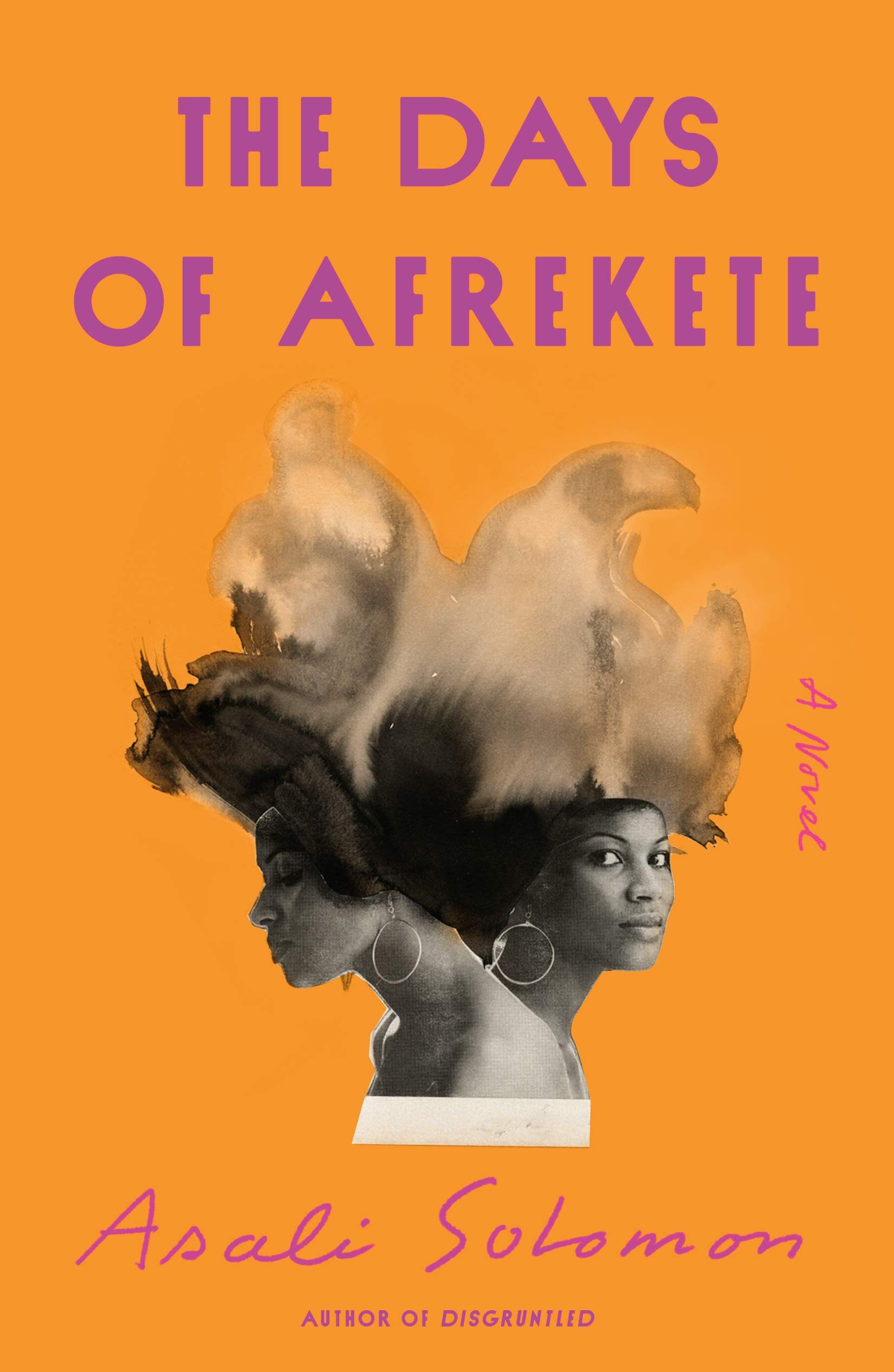

POROCHISTA KHAKPOUR: The Days of Afrekete (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $26) is another outstanding book, following up on your 2006 collection Get Down and your 2015 novel Disgruntled. I just love how you’ve created this incredibly intimate and yet expansive portrait of the complicated friendship of two women at middle age, who have all sorts of identity issues to reckon with—race, sexuality, class, everything. The fact that it is inspired by Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Toni Morrison’s Sula, and Audre Lorde’s Zami also made it extra-satisfying to read. To what degree do you think it’s important for readers to know those books in order to enter your universe?

ASALI SOLOMON: It’s one of those things that functions at a level for people who have already read those books and functions at a different level for people who haven’t. But I don’t think it’s necessary to get. Different people have different kinds of experiences. I always liked that kind of intertextuality and paying homage.

My first and second books came out roughly around the time yours did, so I always consider you of my graduating class. And it’s like each time it feels like starting over. I’m wondering, at this point in your life, how do you feel about these waves of discovery and rediscovery?

Yeah, I mean, it’s funny. I have extremely low expectations in this regard. So, people will say to me, “Oh, your book is coming out, are you excited?” And I’m like, “Oh, I don’t exactly know what that means.” So, I tell my students that if you want to be a writer, the main thing you should want to do is write.

And not just write on social media, where I am a lot! I feel like you are not on social media so much.

I’m not on social media much. I have a Facebook account, but even that, I’ve had to think about a lot. And increasingly I think technically part of my job is to be on social media again. But my problem is that I think I can either do that or write. It’s too much of a constant performance.

It has gotten extremely difficult during this pandemic. And especially right now where a lot of people think we’re coming out of the pandemic, which is, again, very questionable.

Very questionable.

When I was reading your book, one of the things that kept occurring to me is the freedom we have as writers, and how much over the years this discussion of prescriptive versus descriptive that we talk about all the time, how warped it’s gotten, especially as we consider issues of identity.

It’s kind of interesting because I read somebody on Goodreads who posted a somewhat negative review. And they were like, “The main character was kind of problematic.” You want to make your character somehow a model for what you’re thinking? That’s not the way literature works.

I have a Ph.D. in English and my specialty was twentieth- and twenty-first-century African American lit. And so, in my literature classes, I teach almost exclusively Black writers. Occasionally, I would teach a satire course, and I’d teach Mark Twain just to hone in on what the idea of racial satire was by a white writer. When I went to Iowa [Writers’ Workshop], I’d really been trained to overwhelmingly focus on using white writers to teach craft. And it was only because of racist and myopic syllabi that I had it ingrained in me at some point that if you were reading fiction by people of color then you were reading specifically about topics and you weren’t simply reading craft. And it was funny because I would have students of color who would write stories about white people, and I would say to them that it is fine if you have something really important to say about this white person, but your character can be a Black girl like you. Or, you know, I had this one student who was from Malaysia and her family lived in Hong Kong and she was like, “It’s too complicated to explain.” I was like, “It certainly isn’t too complicated to explain.” And then finally I realized that I was doing the same thing in the syllabus. And so after that I decided that overwhelmingly my syllabi would be people of color because I’m teaching craft, and they’re the best examples of craft, and the number of different kinds of perspectives and different approaches is as wide as anything else.

Definitely. And I love the humor here, and that at parts you let the humor be uncomfortable. That to me is a sign of someone doing the real work well. There may be some people who pick this up and think, These characters and what they’re saying, I can’t handle it.

There are certainly in some of the responses a kind of like, OK, so this may not make us feel good. And I didn’t go out of my way to try to make the reader feel bad—I’m just not known for not saying what I think. I’m not like, “Oh, I’m outspoken” or anything like that, but I think a lot of times I really feel like, “OK, you can handle this!” And humor is really important to me. And I think that in that sense, the greater the risk, the greater the reward.

One of my mentors and good friends is Danzy Senna, and I kept thinking of her work and her husband Percival Everett’s work, and their very particular uses of humor and satire around issues of identity. I was laughing out loud like I do with their work at so many points of this.

Danzy Senna and Percival Everett—I spent a lot of time with their work and, you know, humor is an enormous part of it. I read Caucasia a really long time ago and I’m pretty sure it burrowed into me. And then I was reading New People and I really like the way that she describes racial and class strata, I owe a lot to that humorous anthropological approach there.

Humor is essential to so many of us. I think about dark humor and Iranian sensibility. The humor actually comes from ages and ages of suffering in our cultures. I felt that in your work, almost as an Iranian!

Maybe there’s a sense of diaspora—a diasporic sensibility, right? So even though none of the main characters in this book are immigrants, there’s a sense of the kind of marginalization and displacement that leaves you to keep one eye open and always also be able to make a joke.

Oh, that’s so good, the diasporic sensibility.

I feel like so many people, whether it’s a white writer, whether it’s a Black writer, whether it’s a lot of us non-Black POC, we’re trying to figure out how can we exist right now in the world as readers and writers. People are struggling with burnout and isolation, but the work is better than ever. So I wonder what can we do as writers, readers, teachers, critics, etc. to work with all this?

I think limiting my social-media intake really reduces the amount of that kind of exhaustion. There’ve been a couple of times when something was going on, and I would be exhausted by just catching wind of it. I can’t imagine being involved in that cycle every twenty-four hours, or all day long.

Presenting yourself on social media is like presenting an idealized version of who you are: this person has to keep in mind how to be humorous, how to be topical, how to say something smart, how not to offend anyone who you esteem! And whoa, that’s a nightmare—it’s like the soul-sucking version of being a fiction writer in a lot of ways.

Yes! It can get really, really difficult to navigate with all the rest of what we do.

The problem is not only do you feel like there’s a professional reason to do it, but it’s also wired into your system, the adrenaline. My husband is not on social media at all. He was like, “Well, why didn’t you turn off the computer . . . ?” And I’m like, “You’re right, you’re exactly right, why did I go after that random racist in Missouri or whatever?”

Exactly! One of the things I kept thinking about as I read—and I am thinking now as we talk—is how many of us consider you one of our greatest authors. I’ve heard people say this and I see it even in the blurbs, like, “Why is Asali Solomon not a household name?” What do you think?

It’s hard to say that one should or should not be a household name, but honestly, I do think that given the kind of writing that I do, given that I went to Iowa, given some of the things that I’ve written about, if my first book were coming out now it would probably be in wider circulation. I remember very distinctly when Jesmyn Ward’s second novel came out and she won the National Book Award—and then the Times went back and reviewed it. And it was like, the only reason she wasn’t on their radar is because she was Black. And so when my first book came out in 2006, there were a handful of Black people who would get reviewed—the big reviews were much more focused on white writers. So there’s still a tremendous amount of gatekeeping, but now I think people say, “Well, if this person of color came through this particular prestigious place, then we should pay them attention,” a little more in the way that they do with white writers.

I still feel like I’ve just started publishing. And so a lot of times I have to calculate the years, but as far as my age goes—and I tell this to my students—it’s not like being a professional ice-skater. It has the potential to get better in some ways. I mean, there’s another problem people sometimes run into, which is that they really only have one story that they want to tell, and they tell it when they’re young. And then after that, it gets kind of hard. But barring that, it’s one of those things that can really just get better and better.

For years I would tell myself Toni Morrison didn’t publish a book until she was almost forty. So, you know, I’m forty-eight—I’m basically eight.

Porochista Khakpour is a novelist, essayist, and journalist. Her most recent book is Brown Album: Essays on Exile and Identity (Vintage, 2020).