MIRIAM TOEWS IS THE RARE NOVELIST for whom “write what you know” does not amount to conservative advice. Toews was born and raised in an insular Canadian Mennonite community called Steinbach. Her eventual rebellion, which included a stint touring North America in a dilapidated VW van with a fire-eating street performer, was nearly as thorough as the rigidity of her earlier life. Toews has shaved her head and hitched rides with punk bands. She has been a single mother on welfare. She has witnessed the debilitating depression that culminated in the deaths of both her father and older sister. Versions of all of these experiences are refracted through her novels, which tend to circle the same handful of themes—misogyny, suicide, mental illness, religious repression—in playful, occasionally slapstick prose that belies the seriousness of its content. Her debut, Summer of My Amazing Luck (1996), centers on an eighteen-year-old-mother living in a housing project in Winnipeg, where Toews attended college and had her first child at twenty-two. All My Puny Sorrows, published in 2014, fictionalizes the difficult end of her sister Marj’s life. While Toews was never dosed with bovine anesthetic and raped like the women living in a Bolivian Mennonite colony whose story she borrowed for her 2018 novel Women Talking, she sees this as merely an accident of history. As she told an interviewer at The Guardian, “I’m related to them. I could easily have been one of them.”

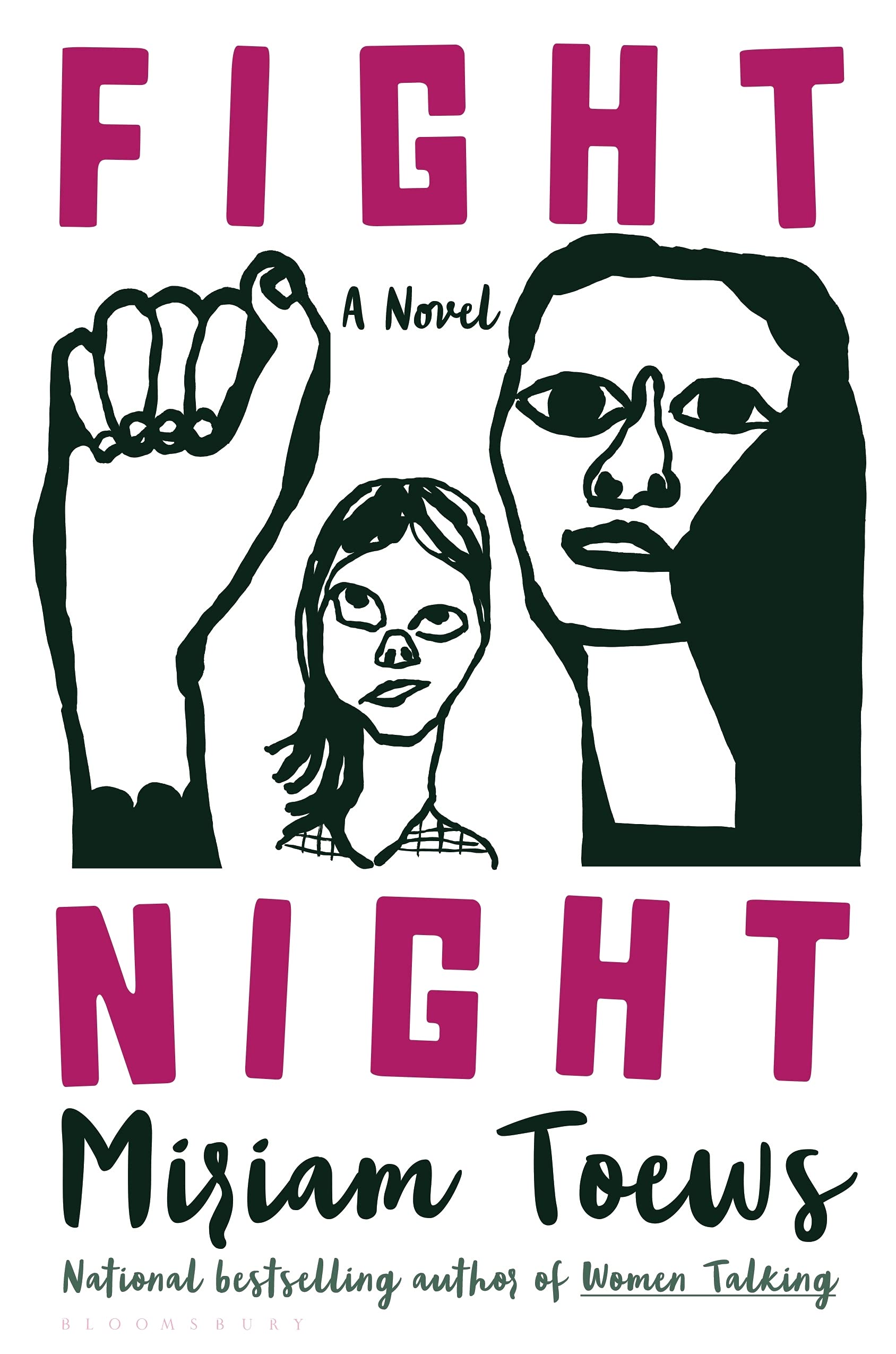

Toews has said she felt unable to write explicitly about Mennonites while her father was still alive, but her family members have been present in her work from the beginning. As Alexandra Schwartz noted in a 2019 profile, there is a character based on her mother Elvira “in just about all” of her novels, “though some of these incarnations are more fictional than others.” In Fight Night, she appears under her real name. Previously, Elvira-like figures have occupied supporting, if load-bearing, roles in Toews’s fiction; here, she takes center stage.

Not as the novel’s narrator, however—that position is taken up mostly by Elvira’s granddaughter, nine-year-old Swiv. (Swiv is also one of the narrator’s nicknames in All My Puny Sorrows, where it’s short for “Swivelhead,” a reference to the way she “was very often looking around for solid clues to what was going on and never finding them.”) Swiv has been expelled from school for fighting, her father has left home, and her heavily pregnant mother is deep in rehearsals for a new play. In these circumstances, Elvira must act both as Swiv’s primary guardian and her teacher. Their caretaking relationship is mutual: Elvira teaches Swiv math, decodes her mother’s opaque outbursts, and inquires after the regularity of Swiv’s bowel movements; Swiv wrestles on Elvira’s compression socks, boils water for her conchigliette, and crawls on the floor to retrieve Elvira’s dropped pills and lost hearing-aid batteries.

Swiv has not always lived with her grandmother. Elvira’s decision to move in was precipitated in part by the death of her elder daughter, referred to only as “Auntie Momo.” Like Toews’s mother, Elvira has lost both a husband and child to suicide. Swiv is precocious enough to feel anxiety about this complicated inheritance, to worry that she or her mother will prove vulnerable to the illness that has already torn through the ranks of their family. Elvira tries to reassure her: “Mom is afraid of losing her mind and killing herself but Grandma says she’s nowhere near losing her mind and killing herself.” But Swiv can’t stop thinking about death. “I don’t want to understand impermanence,” she complains at one point. “I realize that,” Elvira tells her. “But the thing is you are in the process of understanding impermanence, whether you want to be or not. We all are.” The only thing that seems to terrify Swiv as much as death is sex, which is to say that she is afraid of growing up.

In Elvira, though, Swiv has a soothing vision of adulthood. Toews has given her central character the wisdom of age but a child’s joy and lack of inhibitions. Elvira has no hang-ups about her body: her gas, her shape, her twisted arthritic toes, the puckered heart-surgery scar that Swiv pretends to unzip when she washes her grandmother in the shower. From homeless men to nurses to airplane stewardesses, there is no person Elvira cannot charm, save one—a corporate security guard whose lobby she threatens to urinate in when her diuretic kicks in and he won’t let her use the building’s bathroom. Her irrepressibility is remarkable for all that she has lived through, but the hijinks of an effervescent senior, rendered in the voice of a wisecracking child, can verge on the too-cute. Above her other traits—encyclopedic basketball knowledge, an anti-establishment streak—it’s Elvira’s determination to crawl back from the abyss that Toews stresses most: “She had to ask herself how she would survive grief and her answer was Who can I help?” However admirable a creed, this hints at a cloying tendency in Fight Night that threatens to undermine the novel’s subtler explorations of family dysfunction.

Aware that her time is limited by a rickety heart, Elvira wants to help Swiv learn to fight like she has. She tells her, “You have a fire inside you and your job is to not let it go out.” Fight Night is littered with imperatives like these. Occasionally they are electrifying, like the conclusion of the litany Elvira recites against the Mennonite men of her youth who “crept in like thieves” and “replaced our tolerance with condemnation, our desire with shame, our feelings with sin, our wild joy with discipline, our agency with obedience. . . . They took our life force. And so we fight to reclaim it.” But the novel’s many lines about fighting more often have the ring of a truism, or a self-help affirmation taped to a bathroom mirror, as when Swiv obligingly summarizes that “fighting means different things for different people. You’ll know for yourself what to fight. Grandma told me fighting can be making peace.”

It turns out that fighting can also be making a grand gesture, like flying from Toronto to Fresno to attend to your nephew’s suffering despite your own age and infirmity—a plan Elvira gets her daughter to consent to only by enlisting Swiv as her traveling companion. In California, they reunite with Lou and his brother Ken, aging hippies who buried their own mother, Elvira’s sister, years ago. Lou is quiet and inscrutable, a bachelor who “lost everything” after having a heart attack while uninsured and who goes on long, solitary walks to quiet his turbulent mind. In Elvira’s presence, though, his troubles seem to melt away. He basks in his aunt’s attention like the sun. The pair’s interactions, in their simplicity and unselfconsciousness, are almost unbearably poignant. “Grandma kissed him,” Swiv says, watching. “She held his old face between her hands and kissed him. Lou put his arms around Grandma and then he put his head on her shoulder and they stayed like that until Ken said we could all go sailing later.”

The Fresno scenes are some of Fight Night’s strongest, so it’s a shame the trip proves to be a short-lived diversion. Soon the novel must proceed to the finale it’s been barreling toward all along. Call it Chekhov’s third trimester. Even Swiv sounds exhausted by the need to get from point A to point B: “Let’s cut to being back home now,” she announces abruptly at the beginning of a late chapter. Back home, a high kick gone awry has landed Elvira in the ICU, her prognosis uncertain. At almost the same time, Swiv’s mother goes into early labor, a circle-of-life cliché whose inevitability feels more like a letdown than a payoff. Toews is an expert chronicler of hospital absurdities, and an ensuing scene featuring Swiv and her mother singing Creedence Clearwater Revival at Elvira’s bedside is affecting. But it also threatens to induce toothache.

In All My Puny Sorrows, the narrator’s sister, a concert pianist, insists that the most important part of any piano performance is “to establish the tenderness right off the bat, or at least close to the top of the piece.” But “just a hint of it,” because

when the action rises the audience might remember the earlier moment of tenderness, and remembering will make them long to return to infancy, to safety, to pure love, then you might move away from that, put the violence and agony of life into every note, building, building still, until there is an important decision to make: return to tenderness, even briefly, glancingly, or continue on with the truth, the violence, the pain, the tragedy, to the very end. . . .

It depends where you want to leave your audience, happy and content, innocent again, like babies, or wild and restless and yearning for something they’ve barely known.

Toews’s fiction rarely comes down on just one side of this binary. But unlike the two books that directly precede it, Fight Night is nearly all tenderness. The uncompromising forces that typically counterbalance Toews’s softness—melancholia, the violence of men’s wills—are relegated to the background or too easily surmounted. Still, there’s great pathos in watching a writer as gifted as Toews turn the same losses over and over as if looking for some way to redeem them on the page, knowing all the while that there isn’t. She admits as much in an observation lent to Swiv, who bristles against attempts by authority figures to domesticate her language: “It doesn’t matter what words you use in life, it’s not gonna prevent you from suffering.”

Jess Bergman is an editor at The Baffler.