AN AWFUL DISCOURSE now heralds spring. It goes by “no kink at Pride.” Seemingly concocted on 4chan as one of their loosely coordinated Operations, it has been propelled for the past few years beyond the imageboard by earnest young queers and crypto-religious moralists, both keen to prevent the nonconsensual sight of leathermen. In 2020, arguments about parade logistics reached a fever pitch. The fact that, due to the coronavirus, parades were more likely to be canceled that year was no consolation. There was a more abstract problem: the question of sexuality in public life was at stake.

Another newly seasonal discourse circulates as “no cops at Pride.” This one grew out of a successful Black Lives Matter action undertaken in Toronto in 2016 for community self-determination of parade programming. Their demands to remove police floats and bar uniformed officers from marching have since been adopted in cities elsewhere in the spirit of abolition. Pride celebrations ritually commemorate the defeat of the NYPD over the right to be queer in public; the two discourses address the same concern. The vestiges of the pre-Stonewall police regime persist in laws across the country like the “walking while trans” ban, an anti-loitering statute that places trans women at risk of a prostitution charge simply by stepping outside. It was repealed in New York State only this February. During the twentieth century, police departments nationwide wielded a stubborn jurisprudence that ran on their expert ability to identify sex criminals by sight, and have been slow to give it up. In New York City, the belief in their centrality to public order was on display in the Gay Officers Action League’s howls at its exclusion from this year’s official Pride programming. Instead, GOAL held its own ceremony, honoring the outgoing NYC Department of Corrections Chief, in whose custody the trans ballroom performer Layleen Polanco had died in 2019, with the 2021 Ally Award.

The “shifting public understandings of homosexuality in the twentieth century,” the legal historian Anna Lvovsky argues, “cannot be fully understood without a history of policing.” Her new book, Vice Patrol, is a useful examination of the legal struggle over the sexual character of the public in the middle of the last century. In particular she illuminates a shadowy figure, the vice cop. Though a central antagonist in queer history, he has mostly escaped devoted scrutiny. Lvovsky draws primarily from judicial rulings and courtroom testimony for her material, but is sensitive to the multidimensional nature of the law. One welcome aspect of her study is its attention to this history as a battle over jurisdiction, with liquor boards, psychiatrists, sociologists, and the popular press all vying for legitimacy as arbiters of public behavior. This choice of object somewhat obscures from view the experiences of those people whose right to the public was already more or less categorically barred. The period Lvovsky examines coincides with legal segregation (one judge reasons that an interracial conversation is itself evidence of guilty motives), and she finds an LAPD officer who explains that the law’s relative disinterest in lesbians was because they were less “innately abhorrent” and women tend to be “more discreet.” Thus the book is a roundabout history of how attempts at erecting a heterosexual public by policing vice gave birth to a new type of public homosexual.

Sodomy was consistently proscribed in the United States from the colonial era until 1961, when Illinois became the first state to decriminalize it. But the charge was neither strictly associated with homosexuality nor regularly pursued until modern policing adopted tools from sexology to apprehend newly visible social types. Lvovsky begins her study of antigay policing in 1933, at the close of Prohibition. In the public understanding, gender-nonconforming people known as fairies populated working-class spaces. An early-’30s vogue called the pansy craze brought strangers to this culture into bars to see the “antics and gestures of the fags.” It was this public intimacy with queer culture, Lvovsky notes, that guided its subsequent legal repression. By the early ’50s, departments in most large cities had formed divisions solely for enforcing vice or sex-related prohibitions.

Following the repeal of the dry regime, a new regulatory system emerged to replace it, in some ways, one reporter noted, “stricter than Prohibition.” State liquor boards began sending their agents to bars to order a drink or four and see if they could catch (or prompt) any lascivious behavior. The threat to bartenders or owners came from charges of knowingly serving alcohol to gay patrons and other “degenerates and undesirable people.” Hearings turned on what a nonexpert witness could reasonably be assumed to recognize as a homosexual. The legal record of this period resembled a catalogue of criminally liable “codes and mannerisms,” Lvovsky writes. Defending his patrons against the charge that they ashed their cigarettes like fags, one Trenton bar owner testified that he smoked the same way; another witness invoked photographs of President Kennedy himself wearing a “bulky Italian-weave sweater” to rebut charges that anyone should have known the patrons by their dress—“nothing unusual about that.”

Lvovsky’s meatiest chapter is devoted to the use of “decoy enforcement,” or undercover officers deployed to parks and public bathrooms to solicit an advance from an uncareful or unlucky cruiser. In most states, it was not just a felony to practice sodomy; there were now a number of misdemeanor charges for seeking a partner in public. In some departments, it may have occupied a majority of the vice squad’s time and personnel. Often selected for their youth or beauty, these cops sometimes went through an astonishing training regimen to prepare them to slip undetected into the demimonde of the sexual psychopath, receiving official guidance on dress, slang, and comportment at a level likely surpassing even the most committed homosexuals. But soon men began sharing stories of being beaten, arrested, or worse from the predatory undercovers and adopted community signals to make clear to both parties that neither meant the other harm. Decoys looking for an arrest began resorting to more and more aggressive overtures to draw a potential cruiser out from behind his discretion. This approach led to more than one instance of officers trying to apprehend a disruptive loiterer only to find they were manhandling an undercover cop.

Though their sympathy was usually restricted to men of their class, judges and prosecutors were often exasperated by these cases and moved to dismiss or lessen charges when they were able. The development of peephole technology proved even less winning at trial. To ensure the genital privacy of men and boys who had to use park bathrooms, cops in many cities came up with methods to discreetly keep them under constant surveillance in case some pervert might be looking. Vice squads installed false grates, drilled holes, and swapped mirrors for one-way glass. Logging hours upon hours watching citizens relieve themselves may have been a thankless job, but for these officers it was worth it. The publicness itself of bathroom cruising seems to have been taken as an affront, and the elaborate lengths to which men went to avoid being seen only proved the enormity of their exhibitionist threat.

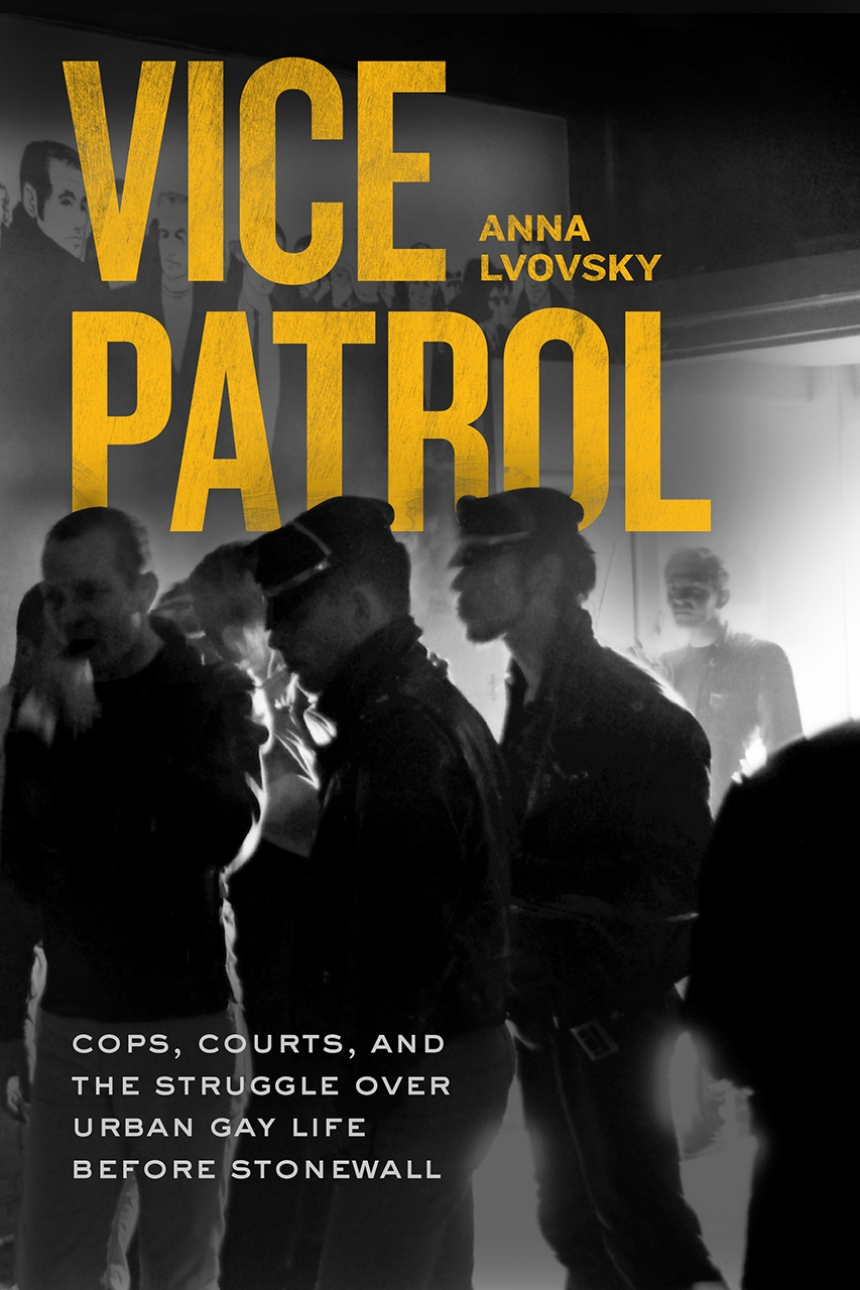

By the end of the 1960s, over thirty years of mounting antigay police operations had yielded a meaningful change in how gays appeared and conducted themselves. The pansies had faded, giving way to a more underground aesthetic captured in a 1964 Life magazine exposé of a gay leather bar, a photograph from which serves asVice Patrol’s cover image. Revelations like these disturbed the public. How could you manage social difference if you couldn’t tell who someone was by looking at them? A rash of press coverage in the mid-’60s “discovering” this new gay world, in Lvovsky’s sharp formulation, “made up for the public’s ebbing mastery over the gay body by honing its mastery over the hallmarks of gay life, reducing the gay world to an object of shared knowledge.” And ready to offer this mastery to the press were the vice cops who had spent endless professionally intimate hours among them, though the more they revealed to the public about their secret deployments, the less sympathetic their jobs seemed to be.

Lvovksy is careful to emphasize that the cops themselves constantly negotiated with other elements in the judicial system. At some moments, this effort reads as an attempt to exonerate the law, whose internal complexity allowed judges, prosecutors, and cops to make “creative” use of their positions to seek their preferred ends. But she makes the compelling point that it was precisely this diversity of views within the repressive arm of the state that gave vice squads their latitude to act. While courts debated whether decoy enforcement was entrapment and prosecutors downgraded felony cases, vice cops gallantly invented new ways to capture and arrest queers, establishing new precedents and legal standards by their own initiative.

Much of the post-Stonewall rights movement was an effort to dismantle this legal architecture by extending privacy rights to sexual behavior and reducing the scope of the public subject to police intrusion. Many liberals and queers understand the regime Lvovsky describes in Vice Patrol to have been vanquished in the courtroom in the last few decades. But this strategy has left in place the same concept of the public as a heterosexual order patrolled by cops that is disclosed in the seemingly perennial discourses about Pride. And not only in discourse. In May, Maryland sheriff’s deputies in riot gear raided an adult bookstore, broke the locks to private booths, and arrested nine men, bringing four charges of “perverted sexual practice,” a misdemeanor enumerated by a state sodomy law on the books despite the Supreme Court declaring such laws unconstitutional in 2003. The historical intimacy of policing with this concept of the public, as Lvovsky shows, may mean that one will not be abolished without the other.

Max Fox is a writer and an editor at Pinko magazine.