IN 2011, WINFRED REMBERT HAD ACHIEVED a sufficient measure of fame to be invited back to his hometown of Cuthbert, Georgia, to celebrate his success as an artist. Rembert’s artworks were sought out by collectors and hung in various galleries, including the Yale University Art Gallery. Growing up in Cuthbert in the 1950s and ’60s, Rembert was subjected to police harassment and beatings and, on one occasion, nearly lynched. He had been paraded through town in chains before being sent to prison. But now Cuthbert was honoring its native son with Winfred Rembert Day. He was presented with a plaque that read, in part, “He refuses to allow the chains of hatred for injustice to hold him a prisoner of the past.” As it turned out, some white residents hadn’t left their own hatred behind. After a visit to the local high school, where Rembert shared his work, an elderly white man in a wheelchair sped up to him and made it clear, using the vilest racial epithet, that he didn’t care how good his art was.

“I think he was one of the guys who lynched me,” Rembert observes when recalling the incident in Chasing Me to My Grave. “Who else would roll up to me and say that?” The chase was an enduring one. His memories—a childhood spent in the cotton fields, an adolescence in the pool halls and juke joints of Cuthbert, and young adulthood on a chain gang in the Georgia state-prison system—form the wellspring of an art that vividly depicts the racist oppression and violence that pressed him at every turn. This is accomplished not on canvas but on leather; he learned to hand-tool impressions on the material while in prison, where he made decorated billfolds and handbags.

Rembert died at seventy-five in his home in New Haven, Connecticut, this past spring, but fortunately, beginning in 2018, he recorded a series of interviews with Erin I. Kelly, a philosophy professor at Tufts, who shaped the book’s narrative, ably preserving his easygoing manner and offhand wit in his recounting of otherwise dire circumstances. The artist chronicles his earliest years living with a woman he called Mama but who was, in fact, his mother’s aunt. His mother had given him up when he was three months old, causing a lifelong sense of loss. An artistic eye shines through in his elegantly natural prose: “Mama was a slim woman, straight up and down. She wore long dresses and short jackets. Her shoes had block high heels, not the ones that’s skinny, and her dresses hung all the way down to her shoes.” Rembert’s painting of Mama and her son on the previous page bears out the description and establishes the book’s modus operandi—Rembert’s recollections are conveyed in both words and images. A sort of call-and-response rhythm emerges as we move forward, marking various events, people, and scenes. Rather than seeming redundant, the entwined forms serve as a gloss on one another, the words providing insights and unseeable detail, the images deepening our sense of the emotional impact of the narrator’s experiences.

Some of Rembert’s childhood encounters with the police are almost comical: when they search for him at his home, he hides in a cotton-stuffed mattress from which he peeps to observe the officers shining their flashlights around the room. Another time, he escapes from the back of a police vehicle by slipping a piece of cardboard between the lock and the door as it’s being shut (“When they got to the jail, I wasn’t in the car. Imagine that!”). Far less diverting are tales of the cotton fields, places of ceaseless toil where he witnesses women giving birth only to go right back to work. Even in this context, Rembert finds visual enchantment: “When the sun goes down, the end of the cotton field looks like it’s on fire—a big fire of orange, yellow, and red, fading away into the trees. It’s just beautiful.” But, he says, “When you get out there picking in it, you change your mind about how beautiful it is.” Several of his paintings show long rows of white puffs and workers with sacks hanging heavily on their shoulders. Despite their obvious burdens, his figures—arms upraised, bodies bent, or caught in mid-sway—are always dignified. Rembert’s images preserve the harsh reality of the fields as well as the workers’ inventive vernacular. In Cain’t to Cain’t II, 2016, the laborers on the left and right sides of the field are drenched in dark dye because, Rembert explains, “You can’t see when you go, and you can’t see when you come back.”

Unmistakable glee marks the artist’s memories of time spent in Cuthbert’s pool halls and bars. A friend named Duck introduces him to Hamilton Avenue, the center of the Black community’s commercial life. Dancing figures crowd together in evocatively titled paintings like The Dirty Spoon Cafe and Soda Shop, yet everyone is individualized, given expressions or movements that convey a celebratory sensation, owing in part, no doubt, to being outside the purview of whites. Couples slow dance, others twirl and kick; arms and legs go every which way in sharp counterpoint to the uniform motions of work. No less suggestive are the nicknames of Hamilton Avenue’s regulars: Cat Odom, Bubba Duke, Poppa Screwball, Poonk, and local legend Black Masterson—a fellow who dared to walk around carrying a visible weapon. In his portrait, he sports a huge silver pistol, a gold pocket watch, and a glimmering red bow tie. “Every person I do,” Rembert notes, “I got a movie about them in my head.”

Of course, the crushing weight of racism was never far away. On the town green sat the “laughing barrel”: whites could call on any Black person to listen to “jokes” at their expense. The Black person was then supposed to stick their head in the barrel and laugh, and they could be punished with six weeks of jail time if they didn’t. “I saw people getting humiliated in front of their family,” Rembert recalls. This wanton intimidation and controlling fear troubled his earliest memories. At the age of six or seven, he was ordered into a barn by a plantation owner who showed him “men’s private parts in jars like pickled fruit.” “Don’t let that be you,” the man said.

In 1965, nineteen-year-old Rembert participated in a civil rights demonstration in nearby Americus, Georgia, that was attacked by the police. He fled in a stolen car, was arrested and beaten: “One thing you just don’t do in Georgia is steal. You can kill somebody and you won’t get as much time in jail as you would if you took something from White folks.” After a year in jail without trial, he flooded the toilet in his cell in protest. An angry deputy entered, and during their brawl, Rembert snatched his gun and took off. The retribution that followed is illustrated with sickening detail. In Wingtips, we see Rembert hanging upside down from a tree as the deputy aims a knife at his genitals. For some reason, a man wearing wingtip shoes halted the lynching and Rembert’s life was spared.

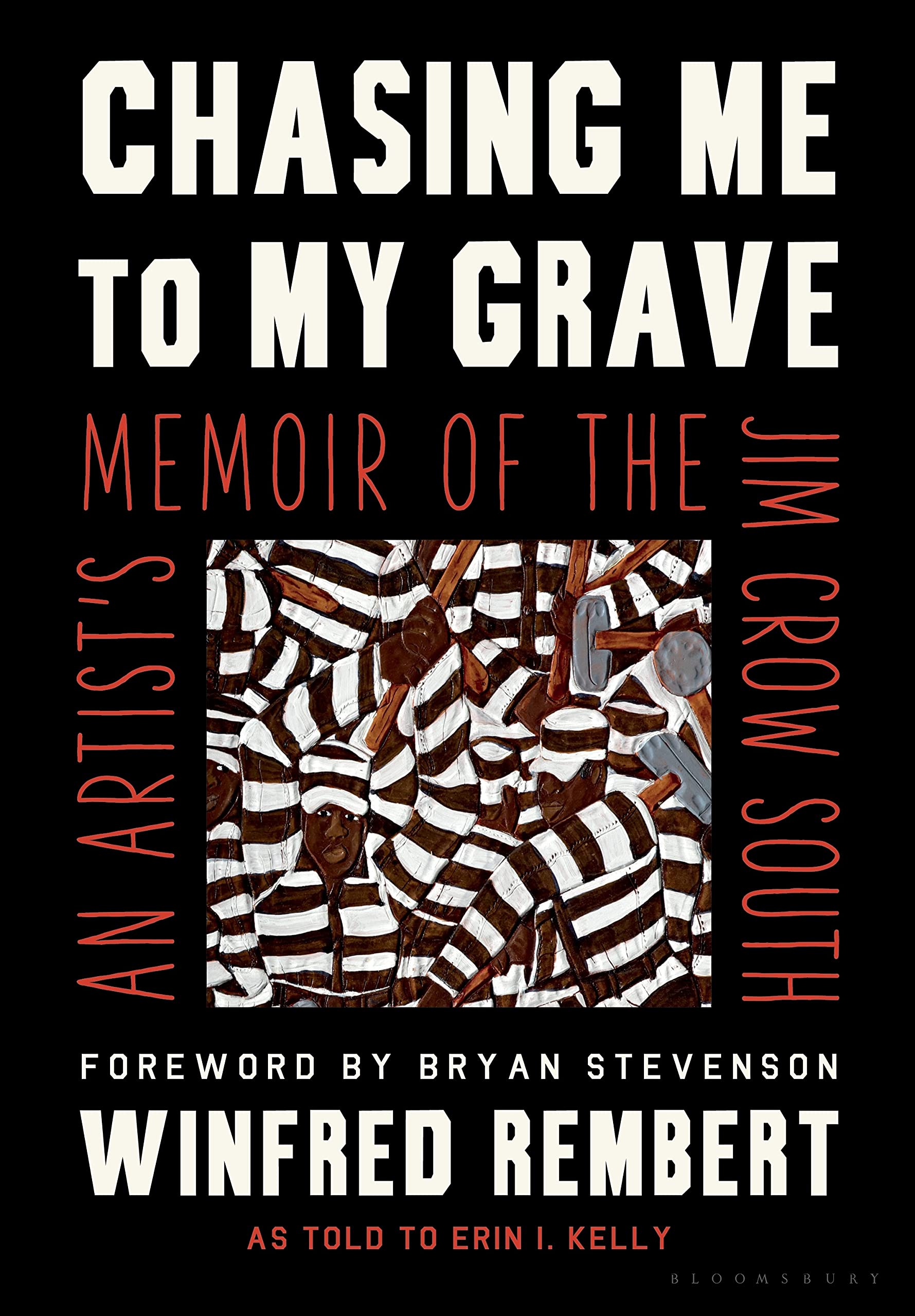

Sentenced to prison, Rembert spent seven years in the Georgia state system, in addition to the two already served in the Cuthbert jail. Chain-gang life required new depths of submission, and a proud Rembert (“I dragged that ball around like it was nothing”) earned ample time in the sweatbox. “It’s like slavery,” he declares, but with a twist: “White guys on the chain gang couldn’t take the cruelty like the Black guys could. They would try to run away and they’d get shot. Black guys wouldn’t take a chance on that. Because the White prisoners were a threat to run, the guards would shackle them to each other. The White boys really turned the prison camp into a chain gang.” All Me, one of his most complex and dynamic images, packs dozens of men clad in black-and-white striped prison garb in a tightly constricted frame. The figures—each one swinging a sledgehammer—merge into a single geometric entity, one so close to vibratory abstraction that the painting requires scrutiny to see what Rembert has done; all the faces are the same, all self-portraits: “Each person in the picture has a role to play. I didn’t want to play any of the parts, but I had to be somebody. I couldn’t walk around and be nobody, so I became all of them. It’s like I was more than one person inside myself.”

After his release, Rembert married, had kids, settled in Connecticut, became a deacon, dealt some heroin, returned to prison, and eventually found his way back to the leatherwork he’d begun years before. He embarked on a pictorial autobiography that moves seamlessly from the intensely personal to the social and political impact of racism, often within a single image. In Looking for My Mother, Rembert portrays himself at about age sixteen, running from the police, walking alone on railroad tracks that stretch the length of the frame. His forty-something-mile trek took him to the town where she lived. “What are you doing here,” she said upon his arrival. Reflecting on the making of the painting as well as the memory, Rembert says,“When you’re walking the railroad, it looks like you’re making no progress. Don’t matter how fast you go or how much time has passed.” Moving from the cotton fields to the Yale University Art Gallery is a kind of progress; returning home to the same racism you once fled isn’t. Rembert’s memoir is cause for hope and shame. It’s a story about running and a story about having nowhere to go.

Albert Mobilio’s most recent book of poems, Same Faces, was published last year by Black Square Editions.