IT TOOK ONLY A COUPLE MONTHS after moving to Memphis for me to realize I was living in a necropolis. You have Elvis’s Graceland temple by the airport; the solemn Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered; a famous cemetery where Isaac Hayes and Sam Phillips are buried and—in case you’re still doubting my assessment—downtown’s hulking black Bass Pro Shops pyramid, where the redneck pharaohs await the endless hunting and fishing of the afterlife. Sometimes I’d feel I was walking not through a city made for the living, but a temple compound dedicated to gods that can’t hear us. And some of these gods were downright evil, like Klan Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest, whose statue required Game of Thrones–worthy political maneuvering to remove in 2017. This apotheosis of the famous dead froze things in time, and not just around the King’s Jungle Room or the classic cars parked in front of the Lorraine. The city celebrated MLK as if he was born, not killed, there, and the extreme racial inequality that outlasted him could hit you with painful irony on his holiday.

“In Memphis, they only love you when you’re dead,” my partner would say.

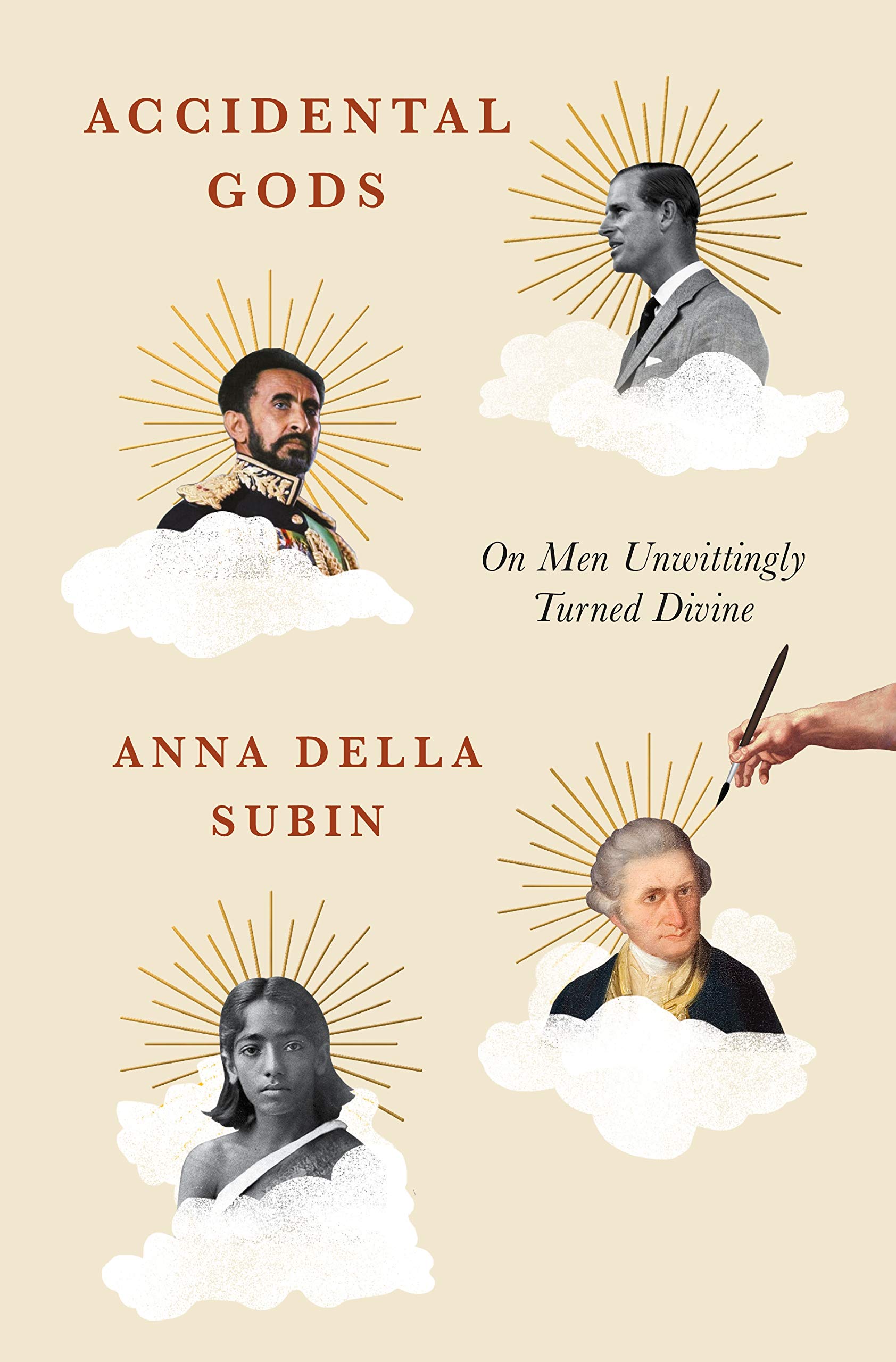

Having lived among this pantheon of gods-in-progress, I was excited by the premise of Anna Della Subin’s Accidental Gods. Subin’s project is a big one: to “speak of men unwittingly turned divine” and explore the ways in which deification has been wielded by colonized peoples and their white oppressors. You’ve seen it in countless movies and cartoons, the old stereotype of backward tribes worshipping white foreigners as gods. It’s a founding myth of America that Columbus and Cortés had the locals bowing down the moment they hopped off their boats. Subin blows this trope open from all sides. She begins by examining a string of twentieth-century men worshipped as gods. After his crowning as Emperor of Ethiopia in 1930, Haile Selassie found himself at the center of a new Jamaican religion, the Rastafarian movement, thanks to growing political unrest under British rule. In the 1970s, Prince Philip learned of his godhood in a much-sensationalized cult on the island of Tanna, where he was absorbed into a larger storytelling tradition deeply misunderstood by foreign press. General MacArthur, appointed Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers after Japan’s surrender, seemingly absorbed Emperor Hirohito’s abandoned divinity and went on to become a god in three continents.

Subin shows the political ingenuity and spiritual creativity behind these acts of deification, how colonial subjects fashioned new gods as acts of resistance. For Jamaicans under British rule, Selassie served as an alternative monarch, a benevolent god-king who didn’t force them to deny their Blackness. Later, Michael Manley, who would become Jamaica’s prime minister in 1972, was able to harness Rastafarian influence in the movement for Jamaican independence. In Africa, a wave of subversive spirit possessions spread from country to country, with mediums dressing in pith helmets made from gourds, channeling the spirits of the occupying forces and mocking their greed. It was rumored that Seyni Kountché—who in 1974 deposed the first, French-backed president of Niger—had been initiated by one of these mediums as a teen.

But Subin doesn’t simply consider how Indigenous people and colonial subjects turned foreign monarchs and generals into gods. She explores how white colonizers saw themselves as ontologically superior, along with the devastating consequences of all this self-theogony. The book, after hooking readers with a modern pantheon of deified men, shifts toward an exploration of how ideas about divinity underlie white supremacy.

To this end, Subin pays special attention to the British Raj and the colonial emergence of the world-religions paradigm, a Eurocentric system of classification that places Indigenous religions on its lowest tiers, if not dismissing them outright as superstitious. She looks at how “the invention of the modern concept of religion, as a private mystical germ, stripped away from any political or economic context,” was used to prove the backwardness of colonized people. Presupposing the irrationality of nonwhite colonial subjects and working off distorted materials from countries they’d never visit themselves, European religious-studies scholars created a self-reinforcing narrative that allowed them to see only what they wanted to see: a superstitious, inferior other begging for foreign rule. With examples ranging from the worship of Gandhi and Nehru to a cult of Hitler in India, Subin then proposes the term “mythopolitics” as a way of understanding how modern politics can be understood as a “metamorphosis of the sacred into new forms.” This section, taken as a whole, is a miniature religious-studies course, divinity school in pill form, and its Krishnamurti arc could be adapted for HBO.

For many Indigenous cultures making first contact with Europeans, the invaders were associated not with divinity but with their arrival from the sea. Translation presents serious problems—conquistadors were playing telephone with multiple translators, and history has largely preserved only one side of that game. Despite strong evidence that few Europeans were actually seen as gods, this notion of European divinity was key to the concept of whiteness, which Subin traces through the American Civil War and into the theology of white supremacy still circulated on Stormfront—a theology that inextricably binds Christianity with a lack of melanin. Subin has a talent for digging up odd cul-de-sacs of thought that reveal the overall absurdity of colonial thinking and racist theology. Some Indigenous people, rejecting the notion that they bore original sin, began to espouse a notion of polygenesis, an idea that there were multiple Adams and Eves and therefore different paths to the divine. This idea threatened a Christian monopoly on salvation, and to refute it, theologians—including P. G. Wodehouse’s grandpa—came up with a theory that serpent worship was present in all human cultures, proving that the Fall was universal and justifying the Christian proselytizing that further justified enslavement and genocide. This echoes the biblical scene from Eden reproduced in Subin’s foreword with perfect irony, in which the serpent promises “Ye shall be as gods.” Europeans—and later, the freshly minted category of white people—projecting their own sense of godhood is the real trespass here, the original sin of our modern mess. “Deicide is on my mind,” Subin reflects, suggesting that the book itself can be seen as an assassination attempt on the myths of European and white godhood, many of which are still taught in schools, used to justify America’s founding systems of power long after they’ve been debunked.

Accidental Gods is one of those carefully researched books of nonfiction guaranteed to make you feel smarter by the end. Subin is working in the tradition of Reza Aslan and Karen Armstrong’s well-crafted histories of (older) gods, breezily navigating several centuries of messy human history and folding in a host of thinkers (Müller, Marx, James Cone), movements (Indian independence, Theosophy), and moments (a tuna-sandwich handoff between the author and her deified friend in Marrakesh comes to mind). Underneath its fascinating parade of ideas and historical snippets, the structure and sequencing are truly elegant. The chapter on Selassie ends with reference to Rastafarian Ma¯oris in New Zealand, and the subsequent chapter picks up the baton in nearby Tanna. The section on the Raj and Indian independence ends with the deification of Eisenhower and Trump in India, bringing us back to the Western Hemisphere for the final movement. This is not a book formed around a single, facile thesis, but instead a complex stitching of evidence. And while many of these chapters make for satisfying stand-alone essays (see “The Apotheosis of Nathaniel Tarn”), the sum is much greater than the parts. With all this sacred ground to cover, Subin keeps a fast clip, sometimes verging on breakneck speed, keeping most of her sources in the notes to foreground the driving narratives. It’s a grand, cinematic style at first, but we get more close-ups as the chapters build upon one another, and the result is powerful and persuasive.

Subin closes Accidental Gods with a meditation on Black theological reckonings with a god that has allowed so much violence against Black people. Reverend Dr. William R. Jones, writing in the 1970s, reexamines the fundamental precepts of his faith in search of an explanation for the apparent divine ordination of systemic racism. Stephen Finley and Biko Mandela Gray, considering the murders of Michael Brown and Eric Garner in 2014, pick up Jones’s thread, arriving at the conclusion that “God Is a White Racist.” The state itself, they argue, must be understood as a white racist god. In light of the four hundred pages that precede it, exploring just as many years, it is hard to disagree with this last point. Subin then turns to a series of séances in New Orleans in which a group of Black intellectuals, artists, and working people commune with the dead: “There is no race, no heaven, no hell, the spirits explained, only the Idea that all people are equal and free and share the same rights and opportunities.” Former slaveholders atone from beyond. George Washington—the ultimate white god—forsakes his Americanness. It’s a touching imagining of the afterlife that, by kicking out a white-supremacist god, makes room for everyone else.

The deified men in Memphis—MLK and Nathan Bedford Forrest especially—exist in the same matrix of violence, political mobilization, and racial hierarchy so brilliantly examined in Subin’s book. It’s everywhere, in America. I’ve just moved from Memphis to Minneapolis, and many times I’ve passed by the intersection on 38th and Chicago where George Floyd was murdered by police. Here, you can see a host of flowers, paintings, and candles, all carefully laid out as offerings. But whereas the message of MLK has been deradicalized and even wielded against Black people by white politicians since his apotheosis, there is something qualitatively different about how Black Lives Matter invokes the dead. It’s a decentralized movement organized by and around ordinary people, and it makes sense that Subin touches on it in the book’s closing pages as she considers the way out of the traps of deification. BLM isn’t trying to turn people into gods. They just want them to be seen as human.

Daniel Hornsby is the author of the novel Via Negativa (Knopf, 2020).