BROOKS BROTHERS USED TO MAKE UNIFORMS FOR SLAVES, you know. It’s true. The company supplied the mid-twentieth-century Ivy League uniform of oxford-cloth shirts, boneless three-button suits, and chunky cricket sweaters primarily because they were known to make good clothes. (Die-hard partisans, however many remain, would insist on the present tense.) That reputation was by then more than a century in the making; in the haberdasher’s antebellum years, enslavers who wanted to show that they didn’t just own people, but wanted to flex, enlisted it to outfit their chattel. As Dr. Jonathan Michael Square pointed out in the fashion journal Vestoj, if you go down to the Historic New Orleans Collection, and ask very nicely, they’ll show you a Brooks Brothers livery coat that most likely adorned the involuntary household help of one Dr. William Newton Mercer.

That W. E. B. Du Bois, the great chronicler of America’s injustices toward its formerly enslaved, born himself in 1868, just two years after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, had a standing account at Brooks Brothers is not really a contradiction, though. Every facet of fine living in this country was wrung from the blood of Black people in chains, so there’s no clean and moral way to get around that. And recall from Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments that Du Bois was a stylish man; that’s why he made such pretty charts about Black suffering.

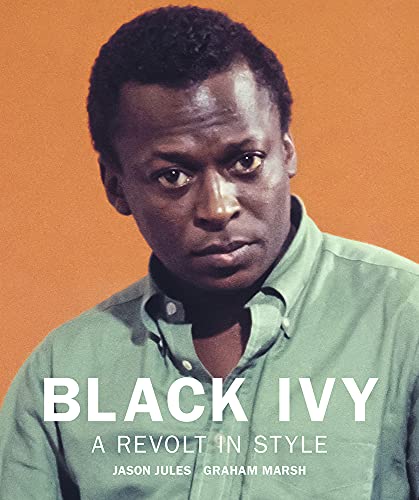

He and a host of other marquee Black men show up in Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style. This book, a perhaps more inert version of the cult-classic 1965 documentary instruction manual Take Ivy, draws its subjects from such sectors as the movies (Sidney Poitier, Duane Jones), the civil rights movement (Julian Bond, John Lewis), and, obviously, the world of jazz. Miles Davis, who graces the cover, is something of a minor deity to latter-day adherents of the Ivy look. Legend has it, he walked into the Andover Shop, the Harvard one, dug what he saw—comfortable duds, systematic but easy on the structure—and emerged with bebop’s costume-to-be. And like bop, the images throughout Black Ivy capture various clotheshorses playing with the codes of the day to create something a little off but beautiful: Amiri Baraka’s chinos are filthy, but he wore them just so—and well at that. It doesn’t matter that the clothes themselves are ordinary and pedestrian; what’s documented here is not a set of breathtaking garments but the flowering and proliferation of a mildly subversive sprezzatura.