GENERICALLY SPEAKING, THERE’S JUST ONE QUESTION driving the Künstlerroman, and it’s “How does this person become an artist?” That narrative-driving “how” relies, however, on the rather more metaphysical matter of “who.” For any artist-narrator worth their salt, this inquiry is depthless—its richness residing in unanswerability, but also in the complicating and exciting fact of art and selfhood’s imbrication. Via Stephen Dedalus and his successors we duly understood that the growth of the person and the growth of the writer are coterminous, that self-knowledge and artistic integrity might, essentially, be the same thing. What happens, though, when the portrait is not of a young man, but of a fuckboy?

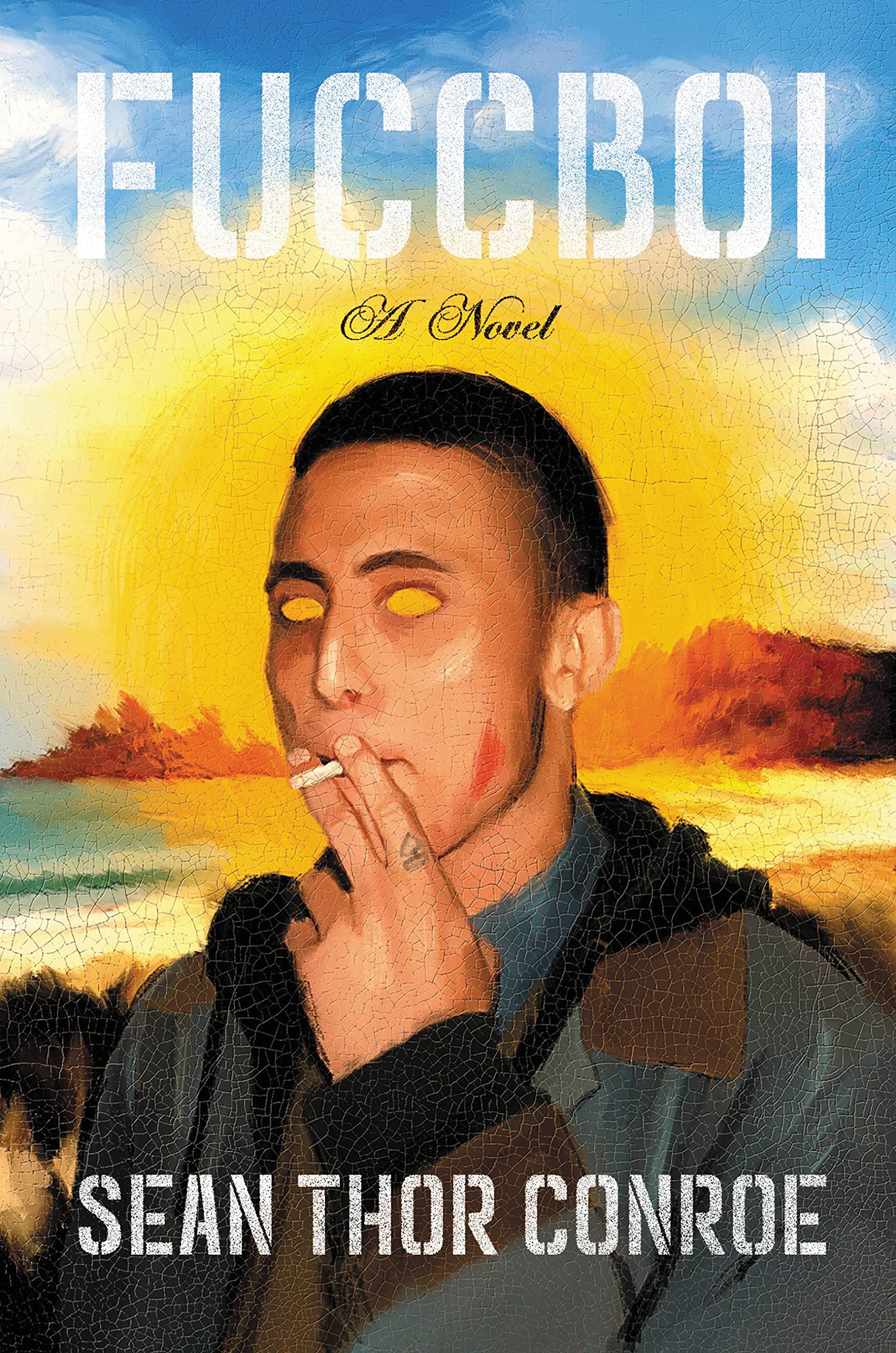

In Sean Thor Conroe’s Fuccboi—a startling, scabrous, big swaggy flex of a debut—we’re one year into Trump’s presidency and many more years deep in the vexed question of American masculinity. Sean, our broke, late-twentysomething narrator, is a failed SoundCloud rapper whose combination of fancy schooling and bro-ish affect sees him hail Heidegger or Nietzsche as “lit” or “fire.” His gender politics may well be “sus af”; the women in his life could be loosely divided into those he’s fucked and those he wishes to fuck. They don’t get names (then again, neither do most of the dudes) but are instead differentiated as “side bae,” “ex bae,” “editor bae,” and so on. The latter expresses concerns about what she calls “the, uh . . . rape-y parts” of his manuscript, a book about an epic, cross-country walk. Eventually, she rejects both it and him. The real-life Conroe has had his fortunes boosted by a six-figure advance, but the outsider Sean within the novel is still trying to find a way to be all about “That Art Life”—that is, to be or become a writer and still survive. He’s getting by in Philly as a delivery boy for the Postmates app, railing Adderall, coffee, and cigarettes to fuel late-night bike runs occasionally flavored with mock heroism: “I was a modern-day hunter, riding my horse-bike around, delivering food to these basic fucks.” Reflecting on this “Out Hereness in technological motion,” he’s moved to yell, “I’m a muhfucking horse rider bruh!” at a passing truck.

On the first page he gets into “a thing” with the cashier in the supermarket. He says the coffee filters are on sale. She says they’re not. A bit of a he-says-she-says, then, and in this way, a foretaste of heterosexual contretemps to come. Except this particular anecdote isn’t litigatory in nature. What matters is not who’s right about whether the coffee filters were on sale (“Honestly can’t remember whether they were or weren’t”) but the way in which Sean and his charisma prevail. Because despite his wrangling, he and the cashier are, according to him, buds from this moment on: “It marked the start of a long, fruitful, and strictly nocturnal friendship.” Sean’s a charmer, in other words, and he’s funny with it. With this opening supermarket incident, the author demonstrates his fictive priorities. Personality is privileged over facts, voice over content. What matters is not what you say, but how you say it. For this bike messenger, it’s all in the delivery.

Conroe is a protégé of the late and beloved Giancarlo DiTrapano of Tyrant Books, a publisher whose relationship to the mainstream was energetically antagonistic. In Fuccboi, a similar attitude presents in two ways, one more successful than the other. First, and most appealingly, it’s in the book’s magnetic voice, specifically, the total commitment to the distinctive argot by which this type of urban, young-millennial American male is recognizable. Reflecting on the rapper Young M.A’s “PettyWap” video, Sean admires how she “[relies] fully on her swag, her charisma, to hold your attention.” This appraisal could also apply to the narrator: there’s a seductive confidence in his full-blown, take-me-or-leave-me style. It’s partly through rap that Sean finds his prose delivery, discovering: “I couldn’t write a book but I could a bar. / And then another bar. / A bar at a time.” So it is that sentences are dropped line by line like successive text messages. (The acknowledgements include: “To Sam Pink, for the early encouragement, and for lighting the way.” Pink is the author not just of several books but also of a semi-viral post from last summer titled “FUCK, BOY!” in which he accused Conroe of stealing his style.) This makes for a distinctive, often very funny prosody, as when we encounter Sean thinking out loud in guileless deliberation over his author name. Should he choose the Japanese version, “Sho Kamura” (Conroe was born in Tokyo in 1991), or go with his American legal name, “Sean Thor Conroe”—“But so Anglo. / All Anglo. / Ignored the yellow half.” And don’t forget gender: “So then: the matronym? / That was woke. / She who raised me. / Why should he get all the names?”

Fuccboi’s style proves to be a more successful vehicle for a fuck-the-mainstream taunt than its substance. Sean is writing in a notebook at a bus stop when he’s interrupted by an “Einsteinian-looking old dude rocking a faded dad hat,” undeterred in his desire to chat. Eventually, these representatives of different generations discover they both attended Swarthmore College. The elder is elated, then incredulous: “‘You went there . . . and you’re writing . . . but’—gesticulating, brow furrowed, like he was piecing together the damn Da Vinci Code—‘now you’re doing’—gesturally dismissing my bike—‘this?!’”

Self-pity and pride mingle in Sean. On the one hand, he’s a muhfucking horserider, bruh, heroically roaming the streets. On the other, it’s freezing cold, he’s working for meager dollars, and he’s soon to develop a horrific skin condition. He declares himself “not interested in writing for people who already read. Who consider themselves ‘literary.’” Adolescently braggadocious, he declares: “More ‘literature’ means more insulated, masturbatory bullshit completely irrelevant to the culture. I’m tryna write for people who don’t read. Who don’t give a shit about books.” The book we’re reading is peppered with enthusiastic mentions of canonical writers, including that bad boy outsider punk Ludwig Wittgenstein (“Witt’s whole point had been that everything that could be said could be said clearly, without any governing rules”). Sean also appreciates Rilke, Debord, Cervantes, Calvino, Ferrante, Bolaño, Sheila Heti, Eileen Myles, Tao Lin, Haruki Murakami, Michel Houellebecq, and David Foster Wallace—none of whom could fairly be called “completely irrelevant to the culture.” So who or what are his targets when he trashes “masturbatory literature”? It seems like a teenage fantasy—some cartoon image of snooty, monocled pretentiousness against which to kick. Relatedly: Sean’s old-guy interlocutor is given the name Seymour, one I associate foremost with the risibly square principal terrorized by Bart Simpson. When Seymour suggests MFAs to young Sean, the response is basically “eat my shorts”:

“All an MFA writer bio credit signals is that you’re churning out more derivative crap. That you’re out of touch with the people.”

“What people?” he asked, genuinely clueless.

Those last two words are a burn: Like, can you even believe this guy? This guy, however, asks a valid question. What does “the people” mean? Those who haven’t attended MFA programs? In which case our man-of-the-people author (alma maters Swarthmore College and Columbia University, annual tuition $54,856 and $66,880) is not The People. As a general principle, the distance between author and autofictive narrator should be respected—this is literature, not life, and this is literature about how a life becomes literature. It is notable, then, that the fictive Sean is not (unlike Conroe, whose biography he apparently shares in all other respects) an MFA candidate at Columbia.

This divergence is related to the question of aesthetic distance, of how an aspiring writer might make himself a character, and in doing so, in the space of that remove, become a writer. For much of the novel, Conroe is operating in a mode of sympathetic uncertainty. When “editor bae” discloses a past experience of rape, we see, for example, a dynamized double consciousness: the defensive, reactive Sean of this moment who cries, “I’m one of the good ones!” and the future, reflective Sean who, limboing up to a low bar of accountability, observes that this “wasn’t about me” and then, more admirably: “Her telling me this didn’t preclude me from those very same tendencies that made him do what he did.” To traduce Wordsworth, here is fuckery recollected in tranquility. But toward the end of the novel, a friend calls him out: “INVESTIGATE YOURSELF, DOG!” The friend continues: “And all this ‘fuckboy’ self-awareness? When does that become reveling in it. Become self-fulfilling.” Sean writes that he’s “still considering this, today.”

Here, Conroe is alighting on the perennial novelistic problem of diagnostician versus patient. Is his novel a vivisection of the fuckboy or a celebration of him? Mostly, we’re in the depthless “who” of the Künstlerroman, where, through being reflexive and morally equivocal, the book is neither endorsement nor denunciation. In other words, it’s literature. At one point, Sean offers a mini-manifesto for writing: “To, as DFW via Rilke put it: disturb the comfortable and comfort the disturbed.” That sounds dialectical and good. We live, however, in Manichaean times; kindergarten morality demands villain or superhero.

Considering the novels of Ben Lerner, a friend recently averred: “He was better when he was bad.” She meant she preferred the guilty, horny, callow narrator of Leaving the Atocha Station to the model man of marches who checks his privilege in The Topeka School. I admire that book greatly, but reading Fuccboi, I was reminded of a late scene in which Lerner’s protagonist succumbs to a burst of testosterone and swats the phone out of the hand of a fellow dad at the playground. How much more daring the novel would have been had it simply ended there, in ugliness. Similarly, instead of staying somewhere in the uneasy realm of “Still considering this, today,” Conroe’s book takes a strivingly exculpatory swerve, and in the process betrays its project.

Abandoning unanswerable inquiry for an embarrassingly binary alternative, Fuccboi finally asks a very dumb question: Is ya boy A Good Guy or A Bad Guy? When Sean sees his neighbor “just going in on his girl K,” he runs to her rescue, fighting off The Bad Guy, while, she, damsel-ish, is “a crumpled heap on the sidewalk, barefoot and tear-strewn.” There are literal cheers. Question answered! He may as well have been wearing a cape. It’s an ending to comfort the comfortable.

Hermione Hoby is the author of the novel Virtue (Riverhead, 2021).