ANDRÉE’S GRAVE IS ALL WRONG, Sylvie thinks. It’s covered in white flowers. This is what killed her; she was “suffocated” by whiteness. Sylvie places three red roses on top of the grave. This scene takes place at the end of Simone de Beauvoir’s roman à clef Inseparable: Sylvie is Simone and Andrée her friend Élisabeth Lacoin, known as Zaza. In real life, there must have been a casket for Zaza, who died at twenty-one, and maybe also roses, but in Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958), where Simone and Zaza’s story is recounted, we hear nothing of the casket or the flowers. If you haven’t leaned over a coffin to adjust a sleeve or set a lock of hair, consider yourself lucky but not exempt. The impulse to memorialize the dead in a decisive final image is as common and propulsive as love. This is what the flowers allowed, and what fiction makes possible.

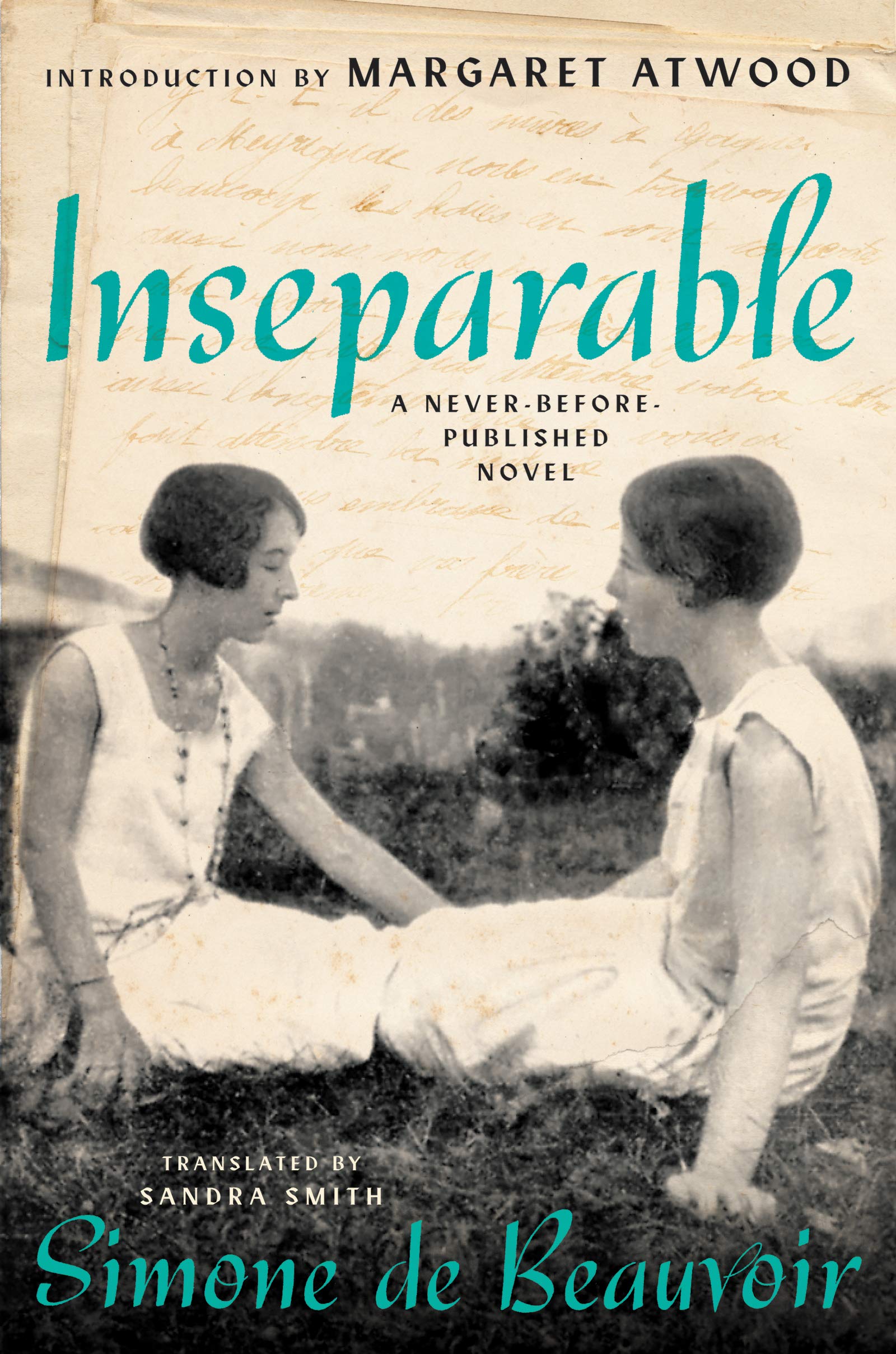

How we remember, the many guises of repression, the shifts between memoir and fiction—these are questions that surround the slim, devastating Inseparable, written in the early 1950s and unpublished during Beauvoir’s lifetime. The novel follows Andrée and Sylvie through their teenage years. Much of the material is reiterated in Memoirs, often word for word. But fictionalizing their story distills its essence and complicates Beauvoir’s own legacy: Inseparable is less a story of female friendship than one of first love.

In Force of Circumstance (1963), the third volume of her autobiography, Beauvoir recalls showing Jean-Paul Sartre an early version of the novel. He dismisses it outright. She readily accepts his critique: “I couldn’t have agreed more,” she writes; “the story seemed to have no inner necessity and failed to hold the reader’s interest.” This is in 1954, and she sets the manuscript aside. This anecdote was the point in Beauvoir’s memoirs when I considered that she might not be a reliable witness to her own life. There’s something off: it’s the tidiness of the story. Sartre’s response could be read as male unwillingness to grant the inner life and material conditions of women as worthy of time and attention. But Sartre had been the one to urge Beauvoir, more than seven years earlier, to examine her experience as a woman for what would become The Second Sex. Throughout his life he lauded (and took from) her work, and he held no veto power in her decisions.

Beauvoir’s novels and memoirs outline her obsession with finding “my equal, my double.” More than love, she sought a companion in intellectual life. This would be Sartre: that was their famous pact. Throughout their fifty-year relationship, Sartre’s position in the cosmology of Beauvoir seemed secure. Almost too much so: the feminist icon, whose life and work was motivated by the struggle for freedom, was so often read—by herself and others—in relation to her great male loves, Sartre and the American writer Nelson Algren. They were her doubles, the ones around whom she made her work. The novel reveals what had always been true: before the men, there was a girl.

Beauvoir’s decision to set the manuscript of Inseparable aside isn’t completely out of character: in the late 1930s she had started and abandoned seven novels, and she would often cherry-pick sections of her life for either memoir or novel. Nor is it disavowal: Beauvoir returns to the story of Zaza, not only in this unpublished novel and in Memoirs but in the collection When Things of the Spirit Come First, in a passage excised from The Mandarins, and in her dreams, where Zaza appears with a yellow face and reproachful stare. Why, then, the abrupt stop to the novel, a book preserved when so many others had been destroyed? In her recently translated letters, Beauvoir writes about how she had hidden the unhappiness of her union with Sartre for fear of having The Second Sex read as a tale of female resentment. Startling revelation—the writer who took up confession as a formal exercise admittedly self-censoring! But censorship is always a product of its time, and self-censorship a sign of what we block for psychic survival.

Inseparable is published with the permission of Sylvie Le Bon de Beauvoir, the philosopher’s late-life companion and literary executor, who heralds the novel as holding a quasi-sacred mission: “To fight against time, to fight against forgetfulness, to fight against death.” These are noble reasons. Isn’t there a simpler one? Women. The novel is a bookend to Beauvoir’s life—written for Zaza, her first love, and seen into print by Le Bon, her last love—and a hinge. Beauvoir’s affairs with women were well-known and well-documented, but she hedged acknowledging the nature of her relationship to women. There were innuendos, suggestions, outright denials. Inseparable discloses a world she could never score with her later life.

Andrée Gallard and Sylvie Lepage meet at convent school at the age of ten. The penitential air, with its “faint odor of sick patients, mixed in with the smell of floor wax in the freshly polished hallways,” is a breeding ground for obsession. Andrée is small and dark. Willful, irreverent, she is set apart from the other girls. Her schooling had been interrupted by a serious accident: as she was roasting potatoes on an open flame, her dress had caught fire, the third-degree burns so severe she had had to remain lying down for a year. Frailty begets lust. “I thought about her swollen thigh under her pleated skirt,” says Sylvie. Andrée has an enviable ease: the brightest in class, she can play the piano, takes up the violin; she can bake and do gymnastics. Within days, Sylvie is under her thrall.

Their intimacy is marked by a certain reserve: they rarely touch and they use the formal “vous” when addressing each other. But within the strictures of decorum they develop their own language, their own world. Their relationship accrues near-hysterical symbolic weight: Sylvie suffers from a cross word from Andrée, from her lack of affection, from perceived slights. She sews her a silk bag, watches Andrée’s maman’s eyes darken. At the start of the next school year, Andrée is away, and Simone is engulfed by ennui. Classes bore her; life is dull and monotonous. Andrée’s presence upon her return is a revelation. “I suddenly understood, with astonishment and joy, that the emptiness in my heart, my gloomy feeling of recent days, had only one cause: the absence of Andrée.” That summer, Sylvie lies under the trees, abandons God, daydreams about Andrée.

Andrée’s happiness is impeded by the demands of her haute-bourgeois, Catholic family whose yearly pilgrimages to Lourdes hardly conceal a Balzacian world ruled by money and influence. Here, Catholicism is a garret with the door locked from the inside. Maman holds the keys. She barrages Andrée with banal tasks to keep her occupied, cuts off an innocent flirtation with a young neighbor. “Enter a convent or get married,” she tells her daughter. After a long struggle, Madame Gallard relents to Andrée attending the Sorbonne, where she studies literature and falls in love with Pascal Blondel (Maurice Merleau-Ponty). For Andrée, self-interest is a foreign land. Her veneer cracks at her sister’s arranged wedding, where Sylvie finds her in the backyard of her country house playing violin to an invisible audience. Later that day, she drops an axe on her foot to avoid a family holiday. “I told you I’d find a way to have some peace, one way or another,” she tells Sylvie, smiling. It’s fleeting: Madame Gallard forbids Andrée from seeing Pascal without a formal promise of engagement; she will be sent to England and forced to sever all contact. Pascal, spineless in the way of intellectuals, mutters something about the temptations of the flesh. (He is also Catholic.) He puts up no fight.

Days before she is set to leave, Andrée falls ill. The doctors can’t determine the cause: it’s meningitis, encephalitis; it’s unclear. At the clinic in Saint-Germain-en-Laye where she spends her final days, she cries out, again and again, for “Pascale, Sylvie, my violin, and some champagne.” Four days later she dies. Early on in her memoirs, Beauvoir imagines a scenario in which Zaza dies, “called away to the arms of God.” “If that were to happen,” she tells herself, “I should die on the spot.” She lives. (For better and worse we survive much of what kills us.) Memoirs concludes with a chilling phrase: “We had fought together against the revolting fate that had lain ahead of us, and for a long time I believed that I had paid for my own freedom with her death.” I rethought what I had known of Beauvoir and her struggle with liberty. Freedom as duty, freedom as a form of loss to the tune of “Pascale, Sylvie, my violin, and some champagne.”

Like many women, I’ve spent most of adulthood defining myself in relation to men. It was a categorical way to break up time: there was the professor, the construction worker, the other professor, the painter, the writer, and so on. I imagined myself through them until the last, when I became too tired to imagine another. Hadn’t I always known another way? To put myself back at the center of my own life would mean to return to girlhood and to find what I’d forgotten to remember.

Janique Vigier is a writer from Winnipeg.