IN 1947, A YOUNG AUDRE LORDE and her family boarded a train from New York to Washington, DC. Along with their luggage, they carried a box of food, including roast chickens, bread, butter, pickles, peppers, carrots, a spice bun, peaches, iced cakes, rock cakes, iced tea, napkins, and a rosewater-dampened washcloth. “I wanted to eat in the dining car,” Lorde writes in her autobiography, Zami (1982), “but my mother reminded me for the umpteenth time that dining car food always cost too much money.” Her mother was hiding the full truth—that Black families could not eat in southbound dining cars—to soften the blows of American racism. Her efforts were in vain. In DC, the family was refused service at a segregated ice-cream store.

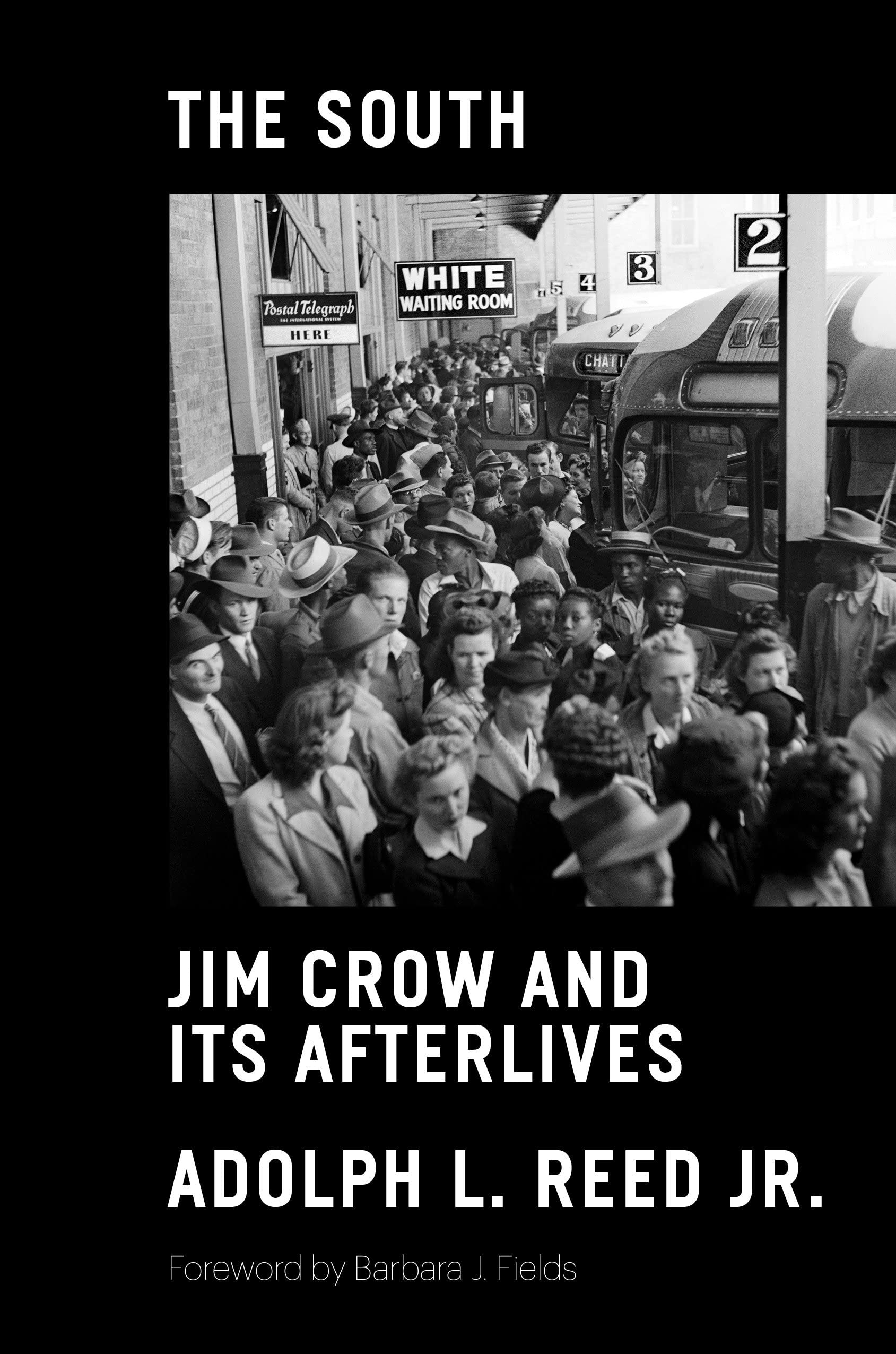

Scenes of northerners learning the rules of Jim Crow the hard way were a common set piece in twentieth-century African American autobiographies. If they have recently declined in prevalence, it is because the last generation that remembers segregation is dying. This generational change is what prompted the Black Marxist political scientist Adolph L. Reed Jr. to write The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives. The book, Reed writes, is an attempt to preserve “the everyday life of the segregation era” before it passes from living memory. Part memoir, part history, and part political treatise, The South chronicles Reed’s life under Jim Crow to correct what he sees as misleading representations of the past. In memorable anecdotes drawn from experiences from Louisiana to the Carolinas, Reed reminds us that separate water fountains and other segregationist hallmarks “were never trivial to those who endured them on a daily basis.”

For Reed, taking segregation seriously means that scholars should avoid claiming that nothing has changed when discussing contemporary racism. After all, he no longer rides Jim Crow; he rides business-class on Amtrak. The persistence of racial discrimination does not prove that Jim Crow never ended. It proves that the economic system it buttressed continues. This is because Jim Crow, in Reed’s account, “appeared and was experienced as racial hierarchy [but] was also class hierarchy.” While the “regime of white-supremacist law, practice, custom, rhetoric, and ideology” that “imposed, stabilized, regulated, and naturalized” that hierarchy has been dismantled, its class system remains. The only way to ameliorate Jim Crow’s lasting effects, for Reed, is to end the organized exploitation that thrived under segregation and that has endured into the present.

Born in the Bronx in 1947 to college-educated parents, Reed spent much of his childhood in the South. There, he learned that most Black southerners did not want “separate developments” so much as “equal opportunity and justice in the here-and-now.” While he was visiting his grandparents in New Orleans in 1953, a zoo worker kept him from riding the horses because he was Black. He cried as his grandmother berated the worker fruitlessly. On another trip, Reed and his grandmother sat next to a physical color line made of chicken wire. When he asked about it, his grandmother responded, “A lot of crazy people ride this ferry and they have to sit on the other side.” Reed learned what it was like to live with the color line in the mid-1950s, when his family moved to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where his father worked as a professor at a Black college. While in school, Reed noticed students who “couldn’t attend school for lack of shoes or a coat” and peers whose school years started late and ended early so that they could work the cotton fields. Each empty seat in the classroom was a reminder of his good fortune.

That life under Jim Crow depended on luck and economic privilege became especially clear when Reed’s family moved to New Orleans. In the ninth grade, Reed was caught shoplifting at a white-owned store. Though he feared being sent to a juvenile reformatory or the infamous Angola prison, the owners simply told him not to steal again. Others were not so lucky. When a fifteen-year-old friend rode in a stolen car, the police arrested him, and he was incarcerated in Angola. “Within a year,” Reed writes, “we heard that he was dead.”

While Black life under Jim Crow was unpredictable, it became even more so during the regime’s collapse. After the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, integration was unevenly enforced, so travelers could not foresee what awaited them on the road. In 1965, Reed rode a bus that stopped in Lake Village, Arkansas. A white couple boarded, and the driver asked two Black students to give up their seats. Reed remembered that the Klan had abducted and killed two Black people about an hour south of where they were. “I realized,” he writes, “how easily the dozen or so of us on that bus could have disappeared.”

As the years wore on, Reed increasingly came to feel that the dangers of Jim Crow were behind him. In Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1970, Reed accidentally walked into an old white man. The man became “irate, and perhaps overwhelmed and disoriented by the crumbling of the old regime.” He waved his umbrella threateningly. Reed walked away and the man followed. Reed prepared to attack him “as a partial repayment for all that he and his ilk had done.” Before Reed could exact his revenge, the old man left. The time in which the white man could expect deference had passed.

This did not mean that race did not affect everyday life. In 1974, at an airport in Mississippi, a ticket agent ignored Reed, pretending to be busy until a white man approached the counter. The agent talked to the white man, and when Reed interrupted, the agent glared at him. Reed then locked eyes with a Black janitor, whose glance seemed to say, “Do what you want, but remember that this is Mississippi. I have to live here, and I didn’t see anything.” The old customs of Jim Crow held on in the form of spontaneous actions from individual actors. But they also decayed, and this difference between living under legal segregation and living with racist acts, for Reed, marked a transition to a new order.

“We were all unequal,” Reed writes of Black people under Jim Crow, “but some were more unequal and unprotected than others. And those differences in social position would prove to have significant impact on the shaping of black politics after the segregationist regime’s demise.” For Reed, this key difference is class. But the memory of Jim Crow often obscures this reality. Of a nurse’s aide in Memphis who asked, in the early 1990s, Reed’s father’s cousin if she could read, Reed remarks that her “presumption was at best vestigial and naive, at worst an all-too-contemporary attempt to assert a superiority.” In either case, things had changed: his relative “probably could have gotten [the aide] disciplined by her employer.” The aide’s position as a laborer determined who had power in that interaction, even if the aide thought otherwise, and class seemed to dictate the law.

In part because of his concern for poor Black people, Reed suggests that politics focused only on Blackness or on white supremacy are not enough. Here, his primary example is the 2017 removal of New Orleans’s Confederate monuments. Erected between 1884 and 1915, the statues were raised as part of a program that “imposed a violent white supremacist social and political order.” Though this regime produced an unequal class system, the removal of those monuments did not produce economic equality. As Reed writes, the politicians that celebrated their dismantling remained committed “to policies that intensify economic inequality on a scale that makes New Orleans one of the most unequal cities in the United States.” The symbolic victory of freeing New Orleanians from white-supremacist monuments is not nothing, but it’s also not equity. After all, the ascension of Black people to the heads of businesses, to the Supreme Court, and to the presidency has not ended the capitalist system that exploits so many.

Whether one agrees with this argument depends on whether one agreed with it before reading the book. Those likely to call Reed a class reductionist will not find themselves persuaded otherwise here. And his polemical tone does lead Reed to make some unnecessary claims: he notes that Toni Morrison’s novels did not represent Jim Crow realistically, for instance, but she never claimed to write history in her fiction (and, indeed, her most famous novel tells the story of the resurrection of a dead baby). But it’s difficult to argue with his contention that anyone opposed to the segregationist regime should also be opposed to the unequal distribution of wealth that typified that system.

One of the enduring lessons of the movement to end Jim Crow is that its more radical economic work is unfinished. This point is made at length by historians of the long civil rights movement like Nikhil Pal Singh and Jacquelyn Dowd Hall. It is also made by Reed’s fellow autobiographers, including Lorde. As recounted in Zami, she traveled to DC a second time, six years later, to protest the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The following week, the federal government outlawed segregation in DC restaurants, and she could have eaten ice cream at the store that once refused her service. “It didn’t mean too much to me by then,” Lorde writes of the ice cream. She had moved on to advocating for economic justice and other causes. For her, as for Reed and so many others, abolishing the system of legal segregation was a beginning, not an end.

Elias Rodriques’s first novel is All the Water I’ve Seen Is Running (Norton, 2021).