IN AN ESSAY ABOUT NATALIA GINZBURG, the Chilean novelist and critic Alejandro Zambra writes, “When someone repeats a story we presume they don’t remember that they’ve already told it, but often we repeat stories consciously, because we are unable to repress the desire, the joy of telling them again.” Of course the compulsion to retell a story is not always situated in joy’s lofty terrain. We might repeat a story in the hopes of shrinking it to a manageable bite, or because it reminds us of another story, or to shine up disagreeable aspects of our lives, or to mock it, perhaps secretly wishing it will deflect mockery from our more vulnerable, foolish selves. All of this is present, for me, in Zambra’s writing, and has been since the first time I read his work, which was around four years ago on the recommendation of someone I’d been on a few dates with. In the desultory landscapes of Bushwick and Greenpoint the snow was comically high, but only in retrospect. Everyone suddenly knew what an NDA was and wondered how to get out of theirs. We talked haughtily and agreeably about literature, and then I said something cruel about his dog, which turned out really to be the only thing, years later, we still talked about. The dog was named after a writer who composed several books of poetry but is best known for his novels.

Some of Zambra’s fictions begin this way—with an oblique romance that wavers like a dart just thrown at a map, with literary leanings and flat bureaucratic types yawning in the background. In fact, the opening lines of his latest novel, Chilean Poet, most strikingly resemble those of his first novel, Bonsai, which was published more than a decade earlier and centers on a pair of doomed lovers (“The first night they slept together was an accident”). Zambra’s fifth novel is in many ways a return to youth, the beauty, the unreliability, and the red-hot indignity of it. Its first section opens in 1991, a year after the official demise of the Pinochet dictatorship, and follows Carla and Gonzalo as they navigate an early romance while living under the roofs of their parents. They are the same age as Zambra would have been at the time, and Gonzalo is from the same part of Santiago as his author. Gonzalo longs to be a poet and subjects his girlfriend to maudlin postcoital readings. Eventually she loses patience, or falls out of love, and they break up.

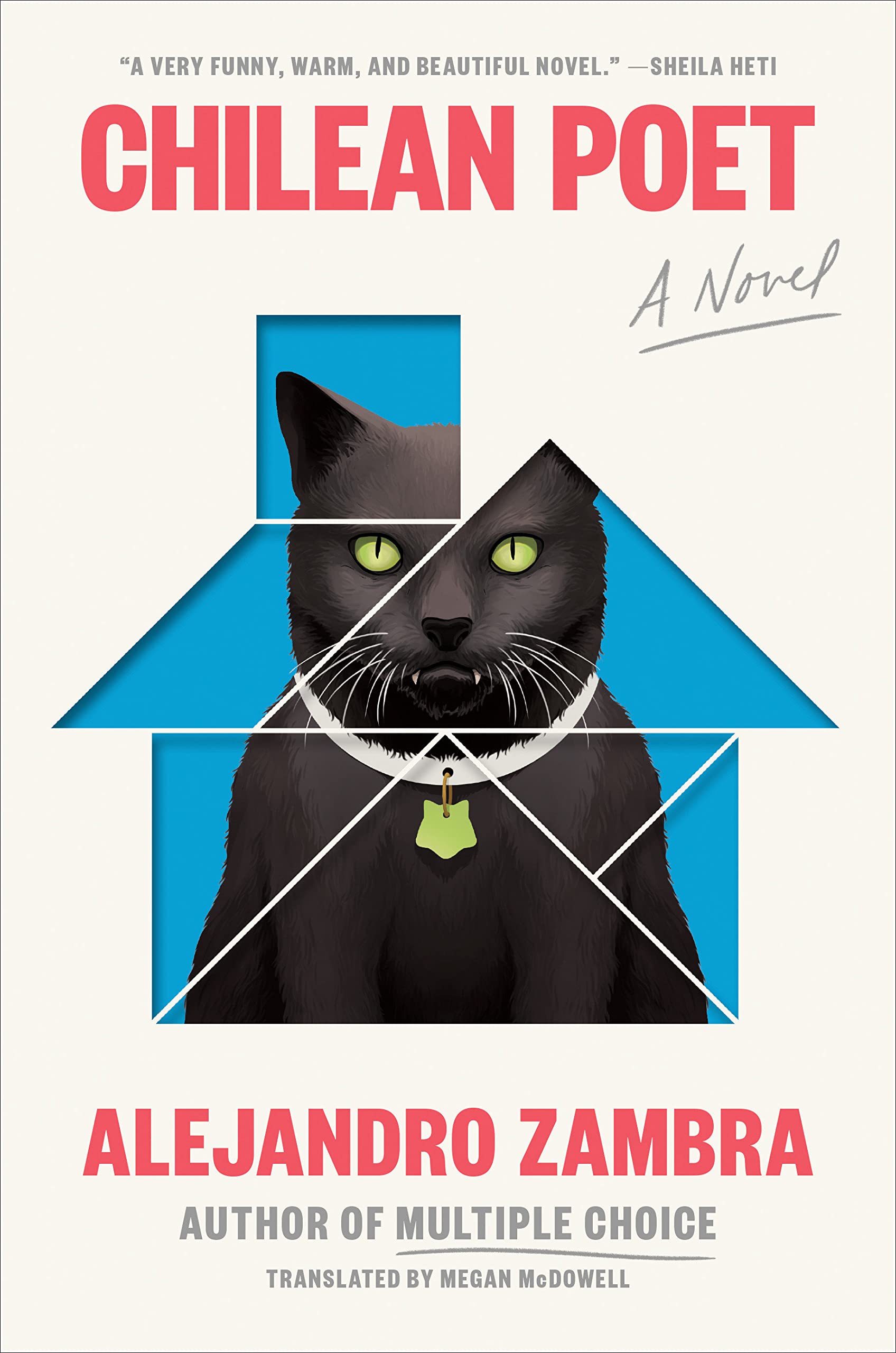

Nine years after the dissolution of their relationship, the two meet again at a nightclub in Santiago and decide to get back together. Carla is separated with a six-year-old son, Vicente, she’s raising on her own, although the father is in the picture too, a little. Vicente is precocious, morally serious, business-minded when necessary. Most of all he’s obsessed with the family cat, Darkness, and addicted to eating his cat food. Some of the funniest, warmest moments in the novel appear in the sections where Carla and Gonzalo, unable to afford veterinary care for Darkness, lie to Vicente about the plausibility of saving their cat’s life. Once Vicente learns of their treachery he adopts various side hustles to raise money for Darkness’s surgery, making a spectacle of his devotion to the cat, adamant about not letting the matter go.

The second half of the novel, as if refusing to grow up, picks up when Vicente himself is eighteen. Having contemplated dedicating his life to building a gym for cats, he’s decided in the end to go the way of his ex-stepfather (for by now Carla and Gonzalo are finished, again) and become a poet, and has begun making some forays into the national poetry circuit alongside his friends, who are also poets. He meets and falls for an American journalist named Pru, who has arrived from Brooklyn rather by accident, running from failed love. Pru contemplates reporting a deep dive into the stray dogs she observes wandering the streets of Santiago but settles on a feature about the local poetry scene instead. Same difference. The interviews unfold in brief, quippy scenes that playfully reproduce Pru’s notes for the essay. Her subjects, each in their own hilarious turn, affect the gamut of pretensions a young poet might adopt, like arguing the world would be a better place if all poets were ambidextrous and stealing Adorno’s line about the futility of poetry in the wake of the Holocaust.

Toward its beginning the novel is heavy on twee machismo that isn’t offensive so much as pesky, and much more prevalent in Zambra’s early novels. Sonnets about performance anxiety, fistfights, “p-in-v sex,” a doctor who finds the need to interject into consultation with his patient that he has never prematurely ejaculated. The narration, again consistent with much of Zambra’s previous fiction, features a cheeky authorial voice who occasionally interrupts the close third to make metafictional cracks (he’d like to follow Pru back to Brooklyn when her trip is over, “but at this very moment there are about a million novelists writing about New York”).

Then there are those signature Zambra sentences, those reckless, rambling sentences that proceed like sleepwalkers traversing the same crosswalk, heedless of traffic lights. A couple down the hall from Carla and Gonzalo are fucking “like rabbits or crazy people or maybe crazy rabbits.” After many years of not speaking, Gonzalo sees Vicente in a bookshop and decides to approach him, “or it’s not even that he’s decided—it’s necessary, it’s natural, it would be unforgivable if he didn’t, and above all he wants to do it, he really wants to, but he needs the momentary refuge of the random sentence; he needs, maybe, to breathe through that random sentence so he can then do this right, supposing there is a way to do this next part right.” Back and forth they go, contradicting, weighing the scales. As for Zambra’s realization of character: nobody is ever not in the mood for sex. Nobody does anything at a reasonable hour if they can help it. Often the women possess a sort of mystical introspective wisdom. The men are not wise, but love fiercely, as does everyone—the women, the children—unless they are a fascist, a fascist schoolteacher, or a deadbeat dad. There is something contrived but comforting, too, about a world where every passion is dispatched at night and every true thought is coupled with a false one—a reading and writing world, and an artistic one regardless of whether its characters make art.

Like the hit singles whose titles litter the new novel like cocktail napkins on a dance floor, this is fiction that provokes a need in you, a curiosity you wish to prolong by returning to it someday: crushing or euphoric emotions (love, regret, giving up, artistic passion) paired with everyday events (using a computer, quitting smoking) and packed in a miniature, highly constrained form. Chilean Poet demonstrates the author’s flair for syncopation, tying in memorable details from previous novels, essays, and stories, to create a veritable Red (Zambra’s Version) of test-prep teachers, important cats, and wives who are late coming home.

Though Zambra’s latest dwells primarily in youth (or maybe it’s even fair to say in his younger novels), it does in many strange and enthralling ways mature as one reads it. Time almost always moves forward—two generations get their moment in the sun, governments transition—but more to the point, the novel’s occasionally self-referential author-voice changes, becomes less tortured and vain, more attentive and funny as the pages turn. This voice never remarks naively upon its own progress or belittles the journey at its end, but changes constantly, subtly, over time and line by line, through processes of repetition. Eventually, Gonzalo reenters the picture, and his more mature, or at least subdued, consciousness accounts for some of this shift. Styles breezily adopted and sanctioned in earlier sections are pulled from the subconscious of the text and dissected, or objectified as punch lines, in later passages. For instance, all that twee machismo narration I found tiresome gets a ribbing when one of the poets Pru interviews declares that “for too many years Chilean poetry was studied as a clash of titans, and those heterosexual macho men fighting over the microphone were the only protagonists.”

As writers know all too well, repetition can sometimes be an agent for change, at the very least in one’s own life. For this to happen the repetition must be imperfect, both organized and messy, a carefully shaped tree that still branches in every direction its nature dictates. The mad method is illustrated beautifully in the story of Javiera Villablanca, one of the poets Pru interviews for her piece, who has worked for twenty years at creating what she calls “translations or distortions” of original poems. Here’s how it works:

Every morning, over her first coffee, Javiera reads a poem by someone else ten times, trying to memorize it. Then she has breakfast with her daughter . . . and drops her off at school, and her day is spent working precarious, badly paid jobs. That’s until eleven at night, when the poet sits down at the dining room table and writes the poem she read in the morning just as she remembers it. The degree of divergence varies a lot, but it’s always there. The idea is to recall the poem many times over the course of the day, and for life, so to speak, to correct her memory.

Javiera’s daily practice echoes other lines from the novel, like Vicente’s philosophy that it’s the poet’s task to notice the details of “every lived experience,” in order “to inscribe them, so to speak, in his sensibility, in his gaze: in a word, to live them.” Or Gonzalo’s insistence that poems get stuck in his head “because poetry is made to be memorized, repeated, relived, recalled, invoked.” Reading Chilean Poet, one arrives at the sense that everything there is to say about literary lives has already been said, but that isn’t at all a bad thing. Forms of writing encourage different methods for reencountering the people, situations, and objects that move us. It takes many resounding voices in the head for a person to believe they understand what matters, or could matter. And these experiences of reliving, recalling, and repeating are already imbued in the ways we collectively speak about our personal infatuations with works of art—when we say, for instance, that we know all the words to a song or that we remember having loved a novel. And then there are poems, which travel a path back and forth between these forms, committed neither to mastery nor memory, because poems we know by heart.

Hannah Gold is a freelance critic and fiction writer based in New York City.