IN COOKIE MUELLER’S 1984 BOOKLET How to Get Rid of Pimples, black-and-white photographs of the author’s pseudonymized friends are presented as befores, dotted with indelible marker, and afters. The diptychs are accompanied by semi-fictional, off-the-wall anecdotes about home remedies. On the cover, Mueller’s own face, photographed by David Armstrong, is stippled in black ink: just a before without an after.

These images of a 1980s New York creative class, drawn-on and dot-less, alongside Mueller’s surreal takes on wellness, suggest a dearth of cures for the maladies ailing this milieu: AIDS, for one. In the five years following How to Get Rid of Pimples’s publication, Mueller, her husband, Vittorio Scarpati, and contributing photographer Peter Hujar would all die from complications related to the virus. And yet at the end of the chapbook, an acne-fighting recipe involving apple-cider vinegar and coconut oil is offered, as if to say, Still, something’s better than nothing.

By the time Mueller died in 1989, she’d gotten used to doling out close-your-eyes-and-hope-for-the-best health advice. Her column “Ask Dr. Mueller” ran during the early ’80s in the East Village Eye, and later in High Times. It was a mix of sincere and sarcastic tips (e.g., “Dear Pietro, This is such a dumb question. You’re just getting sick of your girlfriend, that’s all. Love, Doctor Mueller”). John Waters, whose films she acted in, said of “Ask Dr. Mueller,” “She totally made it up and told people to do things that made people go crazy, stuff that was really bad for you!” Dennis Cooper, in a review of the posthumous collection Ask Dr. Mueller: The Writings of Cookie Mueller (1997), wrote that it “functioned entirely because of the incongruous and heady premise that someone with her résumé could be an expert on medical matters.”

The résumé in question is that of It Girl, ingenue, Dreamlander (the term used to describe repeat cast members in Waters’s films), muse, fiction writer, exotic dancer, fashion designer, tattoo artist, scene reporter, and single mother. Mueller’s reputation preceded her, and like anyone in her position, she was tasked with living up to it and then explaining herself. “Ask Dr. Mueller” was illustrated with a cartoon bombshell grasping a stethoscope, one manicured finger left seductively limp. In reality, Mueller had, by all accounts, bad skin, gnarled hair, and a beauty that was difficult to capture, even if many of the most iconic photographers of the time, including Robert Mapplethorpe, Nan Goldin, Mark Sink, and Kate Simon, attempted it. Many of her published stories are fleshed-out anecdotes about how she found herself so sought after, artistically. From here, it’s easy to compare her to the It Girl, Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol Superstar, who died of a drug overdose the year after Mueller’s first movie with Waters came out.

In a 1965 Merv Griffin Show appearance, Sedgwick, speaking for a stubbornly mute Warhol, describes his film Sleep (1963): “It’s an eight-hour movie and the camera’s on somebody and all they’re doing is sleeping. . . . That was all before I got in on it. Now it’s all changed.” Mueller had a similarly galvanizing effect on Waters’s process: they met in 1969 at the Baltimore premiere of his first feature-length film, Mondo Trasho, a movie he later said was “way too long, but it was influenced by Warhol and all those movies that came out that were, you know, seven, twelve hours of somebody sleeping.” His next movie, Multiple Maniacs (1970), featured Mueller as “Cookie Divine,” delivering the snarling yet blasé dialogue for which he’d become best known.

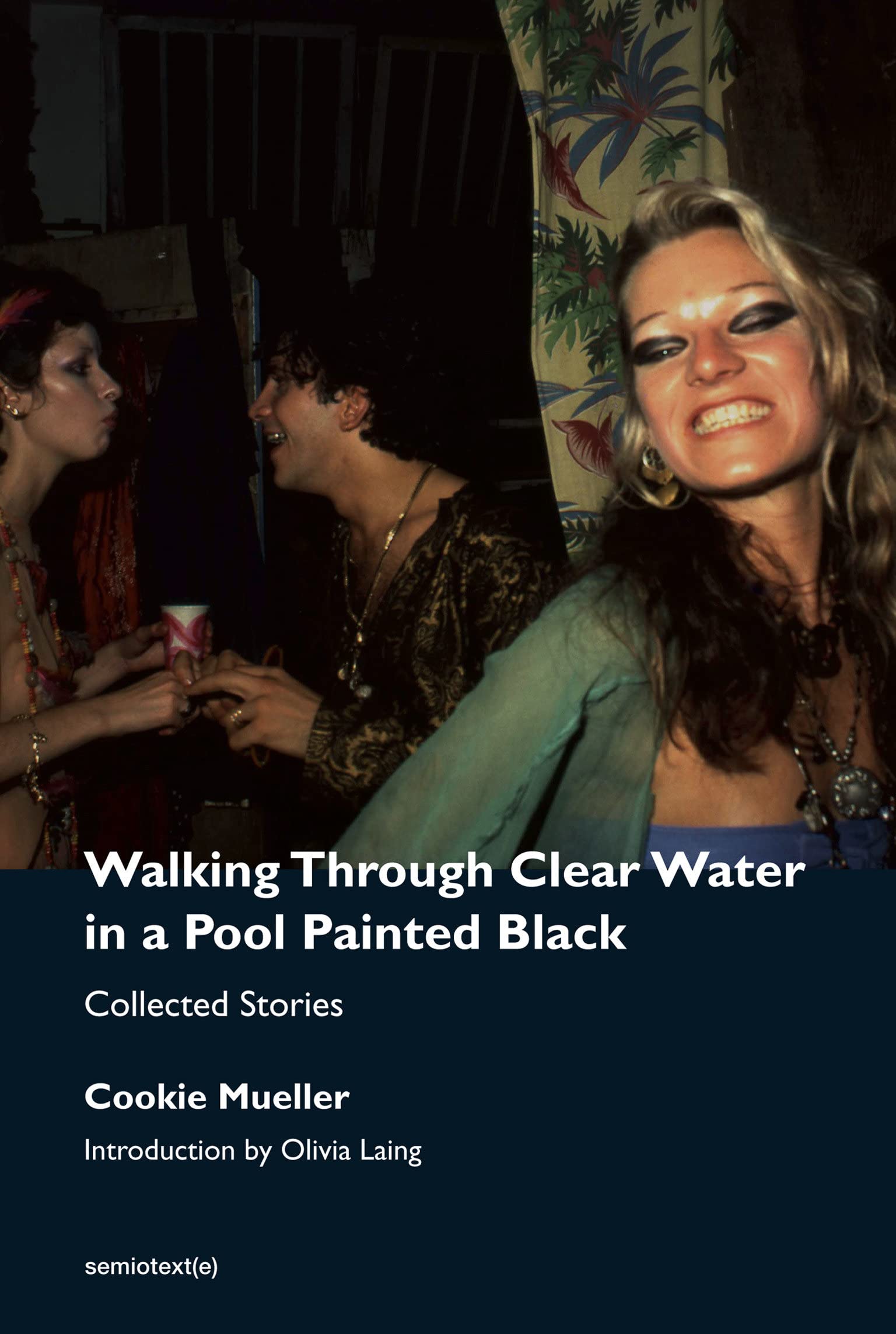

Like a Superstar, Mueller eventually moved to New York City and became a barometer for successful parties there, acting in art stars’ film and stage projects, and making a name for herself as a blissed-out hustler with winged eyeliner. Her path diverged from Sedgwick’s here; Mueller, an aspiring writer since she was a child, wanted to tell her own life story rather than letting someone else have it. A fixture of certain literary crowds, she occasionally got work writing for magazines like Bomb and Details. In that way, she’s more easily compared to the “party girl” writer Eve Babitz; or to the writer-director who called Mueller his muse, Gary Indiana; or to the writer-editor who ended up publishing her most pivotal work, Chris Kraus.

Originally published in 1990, Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black was the first title in Kraus’s Native Agents series, dreamed up as a mostly feminine, mostly American “antidote” to Semiotext(e)’s mostly masculine French-theory translations. The title, chosen by Semiotext(e)’s founder Sylvère Lotringer, came from a line in the story “Route 95 South–Baltimore to Orlando”: “The sky was like black cotton batting that enveloped us in a way that felt like walking through clear water in a pool painted black.” The double simile and repetition of “black” is exemplary; much of the writing is this poignant and unlabored, reading like an extension of (or inspiration for) the drawled poetics in an early Waters film. Semiotext(e)’s recent reissue has almost tripled in size, adding texts that had been edited for Ask Dr. Mueller, a novella, and eight previously uncollected works, four of which are previously unpublished.

The material offers a more developed picture of Mueller’s short life. Her signature smirking asides, pressed between rape scenes and overdoses, are always summed up with a smiling shrug, often with the words “Oh well.” But in some of the book’s newer additions, Mueller’s rough edges aren’t as polished out. “The next time you find yourself climbing out on a ledge, give me a call,” she writes in the previously unpublished “Manhattan: The First Nine Years, the Dog Years.” A consummate optimist, she would know how to talk anyone off a ledge, naturally. And yet the story’s second section begins, “Lately, a couple of my girlfriends have committed suicide.” In “Art and About,” a diary she kept for Details, she writes of the late ’80s, “Never have so many with so little become so big for a duration of time so short. Never before has such a shiftless bunch of life’s lightweights hewn such formidable nests for themselves in so many people’s minds. . . . This is the age of the fleeting media stars.” It’s difficult to know how self-deprecating this insight is meant to be. At the time, Mueller was still mostly known as an actor in some Waters films, in which she was never the star. It wasn’t part of her shtick to admit it, but she was insecure. As Waters later said, “Had Cookie lived, she would have gotten facelifts. She got one when she was alive, and it didn’t do one thing! She got a cut-rate one.”

In “Ask Dr. Mueller,” the author dryly underscores the flaws in her advice column—in any advice column, for that matter—while holding out for the possibility that she has some wisdom to offer. A drug addict who, according to fellow Dreamlander Linda Olgeirson, “felt that heroin was a preserver . . . that it made you live longer,” Mueller fostered a genuine interest in alternative medicine and the power of positive thinking. In one column, she writes, “And don’t worry about AIDS, for God’s sake. . . . If you don’t have it now, you won’t get it. . . . Not everybody gets it, only those predisposed to it.” And, “If you’re not in the high-risk group you’re really being ridiculous. . . . Keep your body very strong and don’t forget your sense of humor”—advice that can only be read, now, as an attempt to make sense of the unfathomable from inside of it.

Compare one firsthand account of Mueller’s breakdown (following a round of shock therapy) to her own account: Olgeirson says, “Cookie was . . . drinking nothing but water and walking around naked, thinking she was invisible. She also insisted that she was speaking fluent French, though she had never learned French.” In Mueller’s buoyant fable “The Mystery of Tap Water,” a character named Julie “believed very strongly in the principle, You are what you eat, so she experimented with water. . . . She was convinced that since she would be only water she could disappear at will. I saw her the night before she disappeared and she was pretty lucid. She told me that she had lived forever, that she would never die.”

Mueller’s legacy is felt more in the worlds of art and fashion, among those who deify iconoclasts, than in literary circles. Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black is a cult classic for writers, though, and the reissue’s new (to us) pieces demonstrate Mueller’s artistic process. They also map out her singular approach to life. In this way, “Dr.” Mueller does have a lot to teach us, at least in terms of wringing absurdity from tragedy, believing in the light derived from darkness. In “Narcotics,” a previously unpublished piece, she writes, “Those people, the dope innocent, the people who never found themselves suddenly in a lowdown compromising situation of heroin need, seemed like adolescents to a junky. . . . Of course the users were actually the stupid ones, but it’s a fact that when junkies become ex-junkies, they’re somewhat the wiser, having seen hell.”

Natasha Stagg is the author of Sleeveless: Fashion, Image, Media, New York 2011–2019 (2019, Semiotext(e)).