THE STORY OF THE STETTHEIMER SISTERS is prestige TV waiting to happen—Jo March meets Hannah Horvath, set against the splendor of money, modernism, and early-twentieth-century Manhattan (with a summer estate or two thrown in for good measure). The eldest, blonde Carrie, was a consummate hostess who, in her spare time, meticulously crafted an opulent dollhouse. Ettie, the youngest, was a brooding Barnard grad with a temper and a unibrow, who, under her pseudonym “Henrie Waste,” once published a book titled Philosophy: An Autobiographical Fragment. And then there’s Florine, the hazy beauty in the middle, who styled herself as an acute observer, her wallflower public persona belying an unforgiving wit. Heavily influenced by the Ballets Russes, she would fling herself into the arts, indulging in everything from painting to furniture design, with a dedication that vaulted her above dilettantism. The youngest of five siblings, the three women cohabited with the Stettheimer matriarch Rosetta (their father was dispensed with early on, never to be mentioned again) in the toniest enclaves of Jewish New York, where their extended family intermingled and intermarried with Bernheimers, Guggenheims, and Seligmans. Ballasted by inherited wealth, the sisters could afford to spurn marriage and instead devote their lives to leisure at its most distilled. Their salons attracted the crème de la Bohème, drawing personalities like Carl Van Vechten, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Marcel Duchamp (with whom Florine waged a complicated—and art historically underestimated—friendship), among actors, curators, ballet dancers, and other domesticated breeds of social celebrity. As Van Vechten quipped, the sisters did not endeavor to “capture lions”; nonetheless, the lions came to them.

In keeping with their proto-It-Girl status, the Stettheimers’ fame quickly dissipated after their respective deaths. In much of the history of the past century, the sisters have been relegated to bit players in dramas starring the Stieglitz circle, Duchamp, or Gertrude Stein (for whose all-conquering nonsense opera Four Saints in Three Acts Florine designed the costumes and sets). But, to quote one of Florine’s most ardent advocates, critic Henry McBride: “Miss Stettheimer’s semi-obscurity was not so much due to the public’s indifference as her own.” The same resources that allowed Florine the freedom to paint also enabled her to set exorbitant prices for her paintings, ensuring that she would never have to sully herself with sales. While she was notoriously “difficult” when it came to showing (she once turned down a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art because she didn’t like the new walls), the missed opportunities eventually grated on her, especially as fellow artists like O’Keeffe triumphed. By the time Stettheimer’s paintings actually made it into museum collections—a provision of her will, whose execution was overseen by her sisters—the rise of Abstract Expressionism kept them out of the limelight. It was only after Linda Nochlin’s 1971 polemic “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” published twenty-seven years after Stettheimer’s death, that the artist was taken seriously again.

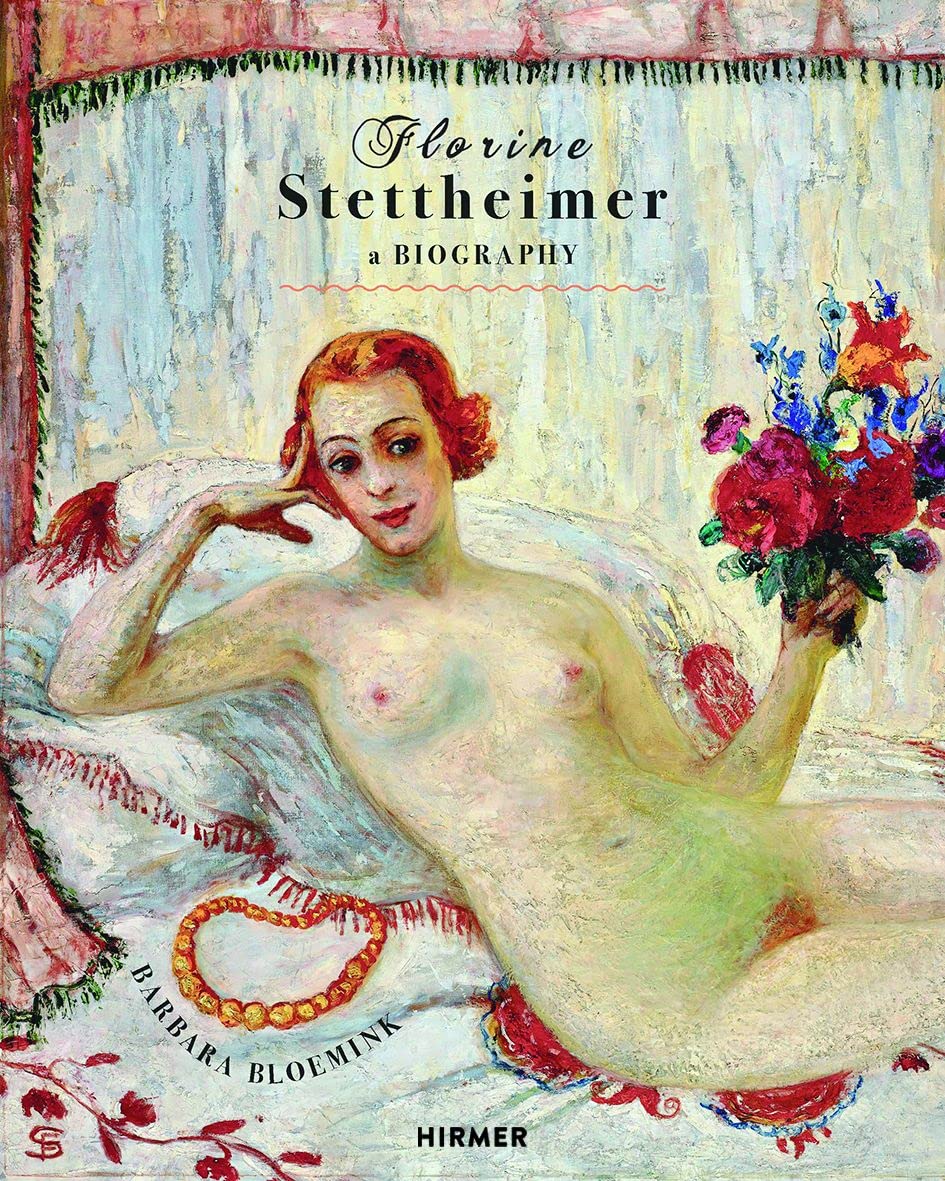

As part of that renewed interest, art historian Barbara Bloemink produced one of the first definitive biographies, The Life and Art of Florine Stettheimer (1995). Now, with Florine Stettheimer: A Biography, Bloemink updates, corrects, and expands her previous opus. Despite its obvious scholarly heft, her writing is suffused with the joie de vivre often attributed to her subject matter. When Stettheimer wanted to covertly paint the opera star Grace Moore, she started frequenting the same salon. Bloemink pulls off a similar stakeout, retrieving glimpses of our fair heroine from diary entries, society papers, and personal letters among the sisters and their inner circle. If anything, the art historian may prove too polite a party guest, gently setting the scene, but letting the more intimate drama play out mainly offstage (for instance, we can never quite pin down the nature of Florine’s relationship with Duchamp). It is only in a few honest paragraphs in the epilogue, where Bloemink admits the artist wasn’t “particularly nice,” that we get a hint of the book that could have been.

First, however, Bloemink must dispense with the books that have been: namely, Parker Tyler’s 1963 speculative biography, Florine Stettheimer: A Life in Art. A film critic by profession, Tyler wrote the sisters like a movie, casting Florine as a shrinking violet who shunned all public exhibitions after her first gallery show fizzled. To be fair, in some of this, the author followed the cues of Florine’s own curt observations—her diary’s record of that fateful exhibition boiled down to “Sold nothing”—but, as Van Vechten tactfully put it, on the whole, the artist was portrayed “a trifle bigger than life.” When Bloemink begins her chronicle of Stettheimer’s life not with the artist’s birth but with the scattering of her ashes (itself a dark comedy, with “Ettie and her paid companion” assigning an unwitting lawyer to dump them), it’s clear that she intends to rid us of Tyler’s one-dimensional caricatures as well.

Up until now, Stettheimer has cornered the market on her own portrait. A careful manager of her own brand, she developed a kind of code for how she presented herself in her paintings (often pairing smocks with red stilettos), and she scrupulously avoided cameras later in life to ensure no unvetted image could supplant the one she had constructed for herself. Bloemink reads this as empowerment, but it also speaks to more than a tinge of vanity. There’s a similar gelatinousness in the author’s analysis of Nude Self-Portrait, circa 1915–16. The work, which reportedly took pride of place over the Stettheimer mantel, has previously been largely ignored or dismissed under the anonymizing title A Model. Bloemink spends much of the third chapter exploring the influences and implications of what she declares the “first nude, feminist, self-portrait by a woman in Western art history.” Yet what Bloemink salutes as feminism seems precariously pinned to Stettheimer’s personal privilege.

In an attempt to foreground the artist’s progressiveness, Bloemink slots some of her more overt social motifs—the “WASP’s nest” Lake Placid Club or the segregated beaches of Asbury Park—under the ill-fitting label of “identity politics.” In the same chapter, Bloemink heralds Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921, the riotous free-for-all in the hallowed luxury department store, as a woman’s perspective on “women pursuing uniquely female activities.” (Never mind that these activities consist of fighting over frocks as the male authority figures look on.) A stronger argument is her assertion that Stettheimer was dismantling notions of class in commodity culture. Similarly, there’s a memorable passage regarding the painting of one of the first Miss America pageants, Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P. T. Barnum, 1924, which describes the artist as subverting the male gaze by concentrating the erotic energy in the tapered figure of the Marquis of Buenavista, a frequent presence at Stettheimer soirees. (Far from virginal spinsters, the sisters were avid—if not downright thirsty—admirers of the opposite sex. Florine may have been a devotee of Proust but it was the Apollo Belvedere she dubbed her “favorite man.”)

And yet the defining relationship of Florine’s life was not with a man, but rather with her sister Ettie. While unrelenting nemeses, the women nevertheless persisted in living together until their mother’s death. Bloemink leaves no question where her sympathies lie, concluding that the “life-time lack of affection between the two sisters was probably due to jealousy on Ettie’s part.” Of course, one can understand the author’s bias. After all, it was Ettie who “ruthlessly” purged her sister’s diaries of their pulp, “editing” out any potentially unsavory passages before the prying eyes of history could see them. One gets the sense that this included personal as well as professional gossip. For instance, Ettie deprives us of learning more about what Florine summarized as the “many horrors” in MoMA’s blockbuster tenth-anniversary exhibition, “Art in Our Time” (1939), which included Brâncuși’s Bird in Space, Picasso’s Demoiselles, and Cézanne’s perilously placed fruit platters.

Ettie was one of Florine’s most painted subjects, second only to the artist herself, perhaps. In the first of a pair of diametric portraits from 1923, Ettie theatrically wallows on a couch beside a burning Christmas tree. (She famously hated that her Jewish family persisted in celebrating the holiday.) Beneath her a blue-tinged moon rests like a bauble slipped from her slender fingers. Meanwhile, the accompanying canvas captures a crimson-caped Florine in Icarus ascent to the sun. In The Bathers, circa 1920, a rather spectacular tableau of Ettie and Carrie in an over-the-top outdoor shower, Bloemink lingers on the broken bobby pin of Ettie’s exposed vulva, a detail that has gone surprisingly unremarked by other historians.

In constructing her portraits, Stettheimer often seized on incidental details. (McBride was amusingly “much astonished” when his temporary fixation on a tennis tournament dominated his 1922 likeness.) Her depiction of Virgil Thomson, the composer who would collaborate with Stein and Stettheimer for Four Saints in Three Acts, is, in truth, a portrait of the opera. The painter foregrounds a stone lion from Ávila, the church that inspired the libretto, while Stein’s mug hangs in the sky like a frosty Teletubby sun. Only the looming black pansy—a none-too-subtle signifier of homosexuality—seems directly related to the sitter. The rest frames him merely as the vessel for the music.

Bloemink runs a similar risk. In her fervor for research, we learn about the outfit “Mrs. Harrison Williams, the country’s perennial ‘queen of fancy dressers,’” wore to the premiere of Four Saints, and, about the various billboards visible in Columbus Circle in the 1930s, when Stettheimer was composing Christmas, but too often the artist is reduced to the sum of her work. Of course, Ettie’s proactive “edits” denied us the gossip and grit to make Florine feel more fully realized. The author might sense—or share?—our longing. She closes her last chapter with a quote from Alfred Barr Jr., MoMA’s influential first director, who wrote that Stettheimer’s posthumously published poems “make me wish I had known her better.”

It’s a perennial problem for any portraitist. In a letter to Georgia O’Keeffe regarding a 1928 homage to her partner Alfred Stieglitz, Stettheimer candidly remarked, “I don’t think I have painted your special Stieglitz—I imagine I tried to do his special Stieglitz—but probably only achieved my special Stieglitz.” In the end, Bloemink’s special Stettheimer is still a Stettheimer worth knowing better.

Kate Sutton is a writer based in Zagreb.