WHEN SUN RA BEAMS into an Oakland, California, community center as an intergalactic ambassador from the council of outer space in the 1974 science-fiction movie Space Is the Place, one of the young men in the crowd asks, “Why are your shoes so big?” Ra, the experimental poet, composer, and jazz musician, is wearing platform shoes gussied up with intergalactic flair, which warrant the flippant and incredulous response. But after Ra is asked if he is real, the mocking wonder of the group of Black earthlings gradually dissipates as he answers, “How do you know I’m real? I’m not real. I’m just like you. You don’t exist—in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights.”

Ra’s assertion may seem outlandish at first, but the argument itself has a long history. In his introduction to The New Negro, Alain Locke, a progenitor of the Harlem Renaissance, similarly contends that, in the American imagination, Black people have largely constituted mythic symbols to fight over rather than human subjects deserving of civil and political rights. Instead of foolishly asking for full citizenship over and over again and expecting different results, Ra presents a more practical solution: let’s leave this planet.

Though Ra’s work is often categorized within Afrofuturism—a Black aesthetic that vividly speculates about times to come—this particular observation could also be read as a precursor to other recent critical trends in Black studies. In asking why Black people should remain tethered to a world that depends upon their abjection, Ra anticipates a central tenet of Afropessimism, a theoretical framework that describes how Blackness cannot be disentangled from slaveness. This work draws from a Black intellectual tradition that traces a network of lines between the current degradation of Black life and the brutal dehumanization of people of African descent since at least the seventeenth century.

In Afropessimism (2020), a book that weaves together memoir, history, and philosophy to elaborate on the theory of its namesake, Frank B. Wilderson III, now a professor of African American studies at the University of California, Irvine, experiences a psychic break in graduate school when faced with the prodigiousness of his work’s implications. If Black people will never be human, as he argues, why continue to approximate a human life? Fighting racism is practically a nonstarter for Wilderson; to rid the world of anti-Blackness would be to deprive the world of the energies that sustain it and usher in the apocalypse. With such an action seeming impossible, Wilderson, at one point, considers leaning into madness as a strategy for wreaking havoc upon conventions of everyday life that keep Blackness in this outsider position. To subscribe to Afropessimism, according to Wilderson, is to subscribe to a “looter’s creed: critique without redemption or a vision of redress except ‘the end of the world.’”

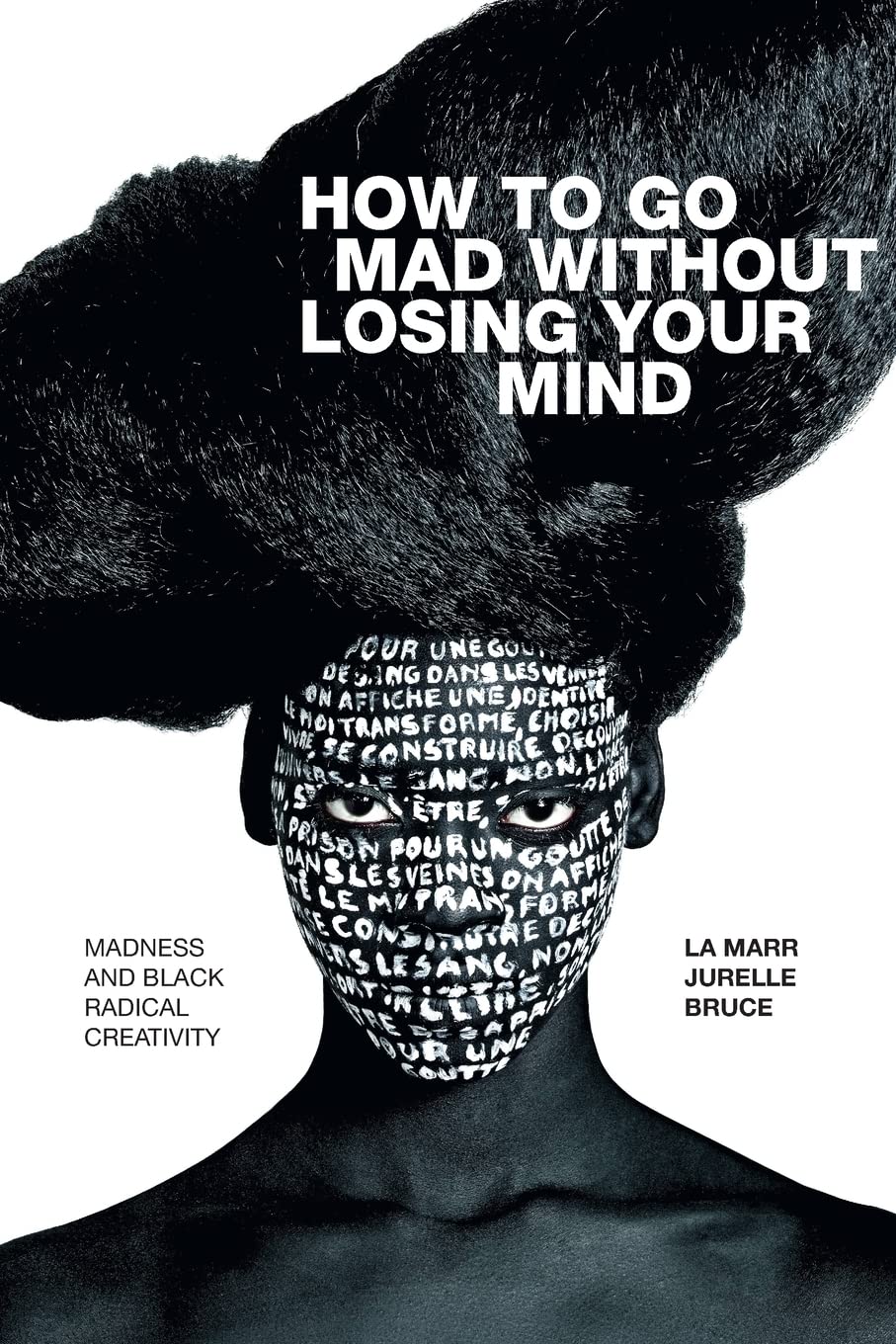

In his new book, How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind, La Marr Jurelle Bruce investigates the work of mad Black artists to explore what madness activates within Black expressive culture. This study covers thinkers like Wilderson, who sees a deliberate rejection of order as a viable alternative to making sense of racism, and artists like Sun Ra, who navigate the world of madness as a matter of both course and choice. For Bruce, “madness” can refer to a deliberate intervention in entrenched racist orthodoxies and a range of psychic states that affect how individuals interact with their environment. With this elastic definition, Bruce carefully considers what such a concept offers to Black art. In essence, even if madness may not usher in Armageddon, Bruce thinks through how it could disrupt calcified ways of thinking and knowing.

Much of Bruce’s analysis traffics in what Björk might call the “possibly maybe.” The book’s subjunctive mood reflects its fidelity to what Bruce calls “mad methodology,” an “ensemble of epistemological modes, political praxes, interpretive techniques, affective dispositions, existential orientations, and ways of life.” Bruce’s deft and thoughtful touch invites readers to dream loudly among a compendium of radical Black artists that few others would think about collectively. With subjects that range from early-twentieth-century jazz cornet player Buddy Bolden to contemporary rapper and composer Lauryn Hill (and many in between), Bruce’s archive reflects the mindful mayhem at the center of his methodology.

Such care is necessary because it would be easy to move from romanticizing mental illness as an unyielding source of strength and vitality to stigmatizing madness as pathological and spuriously outside of the normal. Bruce avoids such argumentative traps by laying out the categories of madness that he finds most useful—phenomenal madness, medicalized madness, rage, and psychosocial madness. These categories overlap and braid together over the course of the monograph. For example, in a chapter on the life and work of Dave Chappelle, Bruce explores an amalgam of the “intense unruliness of mind” that mad subjects experience due to phenomenal madness and the seemingly uncontrollable rage at the center of Chappelle’s ceremonious departure from his lucrative and award-winning sketch comedy program, Chappelle’s Show. Elsewhere, Bruce interprets Nina Simone’s civil rights anthem “Mississippi Goddam” from multiple perspectives, considering not only the public’s distaste for particular kinds of deviations from the norm (which he labels “psychosocial madness”) but also Simone’s actual experiences of living with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (or, in his terms, living “with medicalized madness”).

Bruce’s movement across his archive is purposefully wayward in order to blow up readerly assumptions and to challenge his audience into reconsidering everything they think they know about madness. A reworking of hardwired approaches to understanding disability (or to recognizing that disability exists in the first place) is difficult work. Since at least the 1980s, the field of disability studies has cautioned us to consider disability as a social and political category rather than simply a medical one. Rationalist readers—readers Bruce names as trusting reason and rationality as sacrosanct Enlightenment principles—would do well to abandon their affinity for the medical model. Such an affinity discards madness as anything other than nonsense. Instead, Bruce extends radical compassion to mad people. As he defines it, this mode of relation “works to impart care, exchange feeling, transmit understanding, embolden vulnerability, and fortify solidarity across circumstantial, sociocultural, phenomenological, and ontological chasms in the interest of mutual liberation.”

Radical compassion is stretched to its limits in Bruce’s reading of Gayl Jones’s novel Eva’s Man. The protagonist’s silence in the face of questions about why she castrated a lover with her teeth could be understood as a reasonable and rational response to the concatenation of violences that are done to her over the course of her life. Bruce, however, takes the radicalism of radical compassion seriously as he challenges readers to see the “individual” violence that Eva commits within a larger regime of violence, rather than simply the logics of the trauma plot. Bruce urges us to extend radical compassion to the character of Eva not simply because she deserves our empathy but because the dismantling of oppressive structures will require that the Evas of the world are a part of our collective future. No one can be left behind; no one can be left in solitary.

Bruce’s argument reaches its most dazzling heights in a more experimental chapter that theorizes what he calls “madtime,” a temporality operating at many velocities. He rehearses and remixes arguments that have appeared elsewhere in the book—on the mad afterlives of Bolden, on the audacious madness of Hill, on the raucous madness of Simone—to speculate about how Blackness’s relationship to time frustrates our notion of the linear as universal and reasonable. Instead, the “manic time” within Hill’s repertoire overwhelms the listener, sonically replicating the feeling of being pummeled by racist institutions. The slow sorrow of Simone’s protest music forces her audience to remain in the present tense of Black pain without moving on from it. The “infinite, exigent now” contained in Kendrick Lamar’s lyrics spurs confusion and disrupts expectations about what Blackness is and what it ain’t. All together, these traipses through various time signatures reveal how the time of liberation will work at all speeds.

How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind begins with an instruction: “Hold tight. The way to go mad without losing your mind is sometimes unruly.” Bruce never forgets this command even as he plays with scale and pacing and logic. He keeps his readers attuned to the possibilities within the conjunction of madness and Black radical creativity. This book, which would have incubated for quite a while in the slow machine of academic publishing, may have actually come out just before its time. As I was reading, I wondered how Bruce would incorporate the extremely public use of anti-trans rhetoric by Chappelle in his most recent Netflix comedy specials or Kanye West’s Sunday Service concerts in the aftermath of his support for Donald Trump. That said, Bruce’s work closes with another imperative direction: “Now let go.” But letting go of a book that feels both so present and so prescient may prove impossible.

Omari Weekes is an assistant professor at Willamette University.