ON JULY 18, 2009, to little fanfare, @ladygaga posted: “I love lee strasberg. he makes me miss school.” Sometimes Chekhov’s gun is a tweet, and this one finally went off more than a decade later when Gaga took on the role of jilted murderess Patrizia Reggiani in House of Gucci and stayed in character for nine months. The public didn’t hear about the firearm discharge until promotion of the film began. Gaga’s (self-)mythologizing press tour coincided with Michael Schulman’s New Yorker profile of Succession star Jeremy Strong, and those wildly disparate elements created a perfect storm of frenzy around “Method acting.” It had long been a catchall phrase for actor-behavior people found pretentious, overly intense, or just old-fashioned annoying, but social media and the rewards it bestows on outlandish pull quotes had divorced “the Method” almost completely from the classification of an actor’s process or training. (Never mind, of course, that Strong stresses in the article that he does not practice the Method; it’s the only passage that didn’t get screenshotted and quote-tweeted into oblivion.) Everyone was talking about the Method and no one knew what it meant.

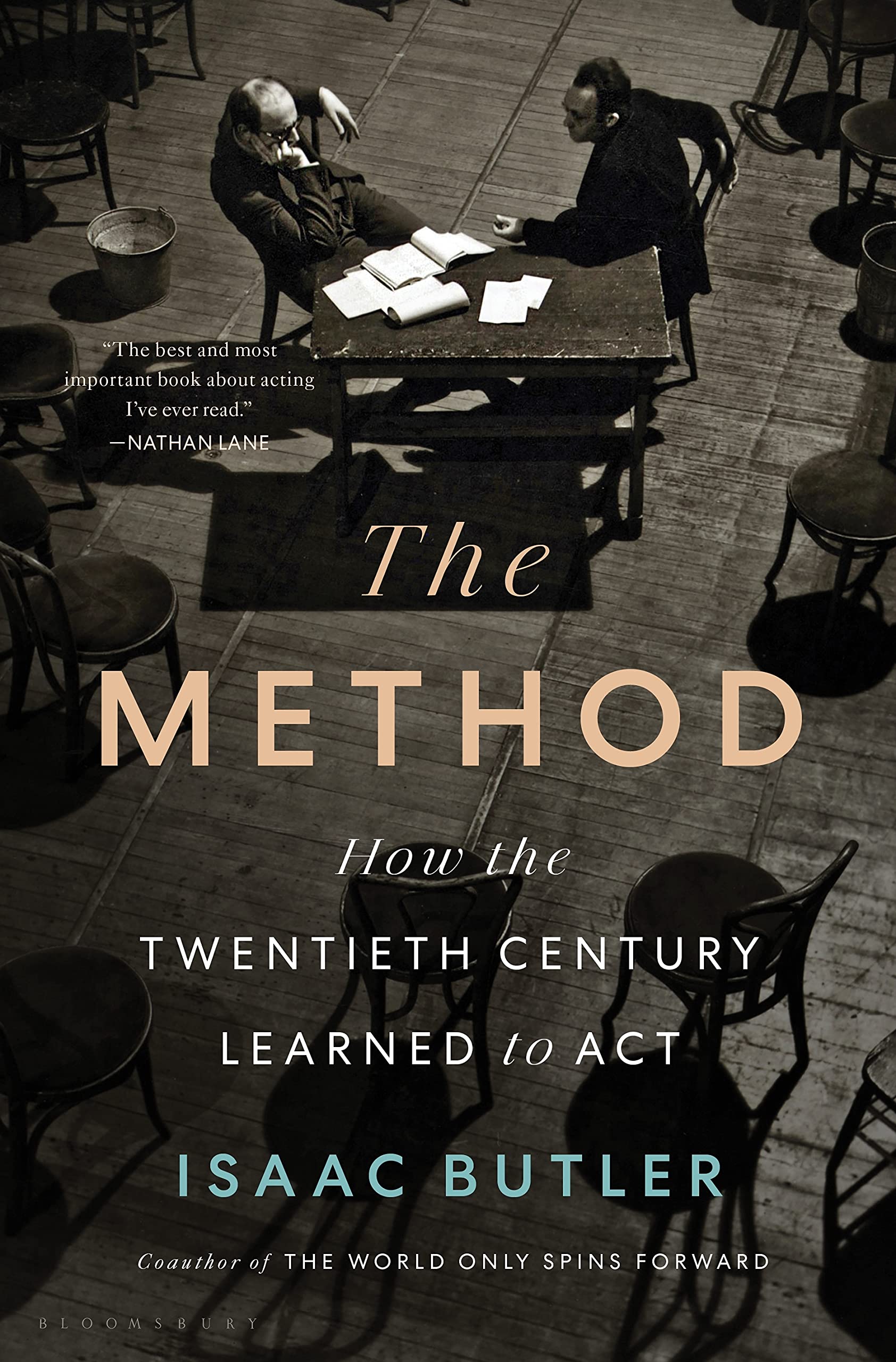

Thank God, then, that Isaac Butler has arrived just in time with The Method: How the Twentieth Century Learned to Act, a history styled as biography treating the Method as a living, breathing thing with “parents, obscure beginnings, fumblings toward its purpose, a spectacular rise, struggles as it reached the top, and an eventual decline.” The onslaught of Strong/Succession talk wound up being a felicitous aperitif for the book, as much of it deals with infighting and power-jockeying amid the dysfunctional family members of the Group Theatre: Strasberg, Sanford Meisner, Elia Kazan, Robert “Bobby” Lewis, Stella Adler, and her on-and-off partner Harold Clurman. All were convinced they were the true artistic successors to the work Russian theater practitioner Konstantin Stanislavski had begun with the Moscow Art Theatre at the turn of the century—what he called his “system.” The young “system,” in the care of Richard Boleslavsky and Maria Ouspenskaya, emigrated to the States, where it was adopted by the founding members of the Group, who gave it a new American name: the method (at first lowercase; Strasberg would give it its capital-M marquee name, taking much of the credit and “riding in a Mercedes with a license plate that read METHOD”).

In the interest of potential-bias disclosure, I must admit I studied at the Stella Adler Studio for four years and was a capital-A, capital-S Acting Student. A “wore all black every day and writhed around on the floor pretending to be various animals whilst a grinning four-foot-eleven tyrant banged a djembe drum and shouted about the flagrant unprofessionalism of the fashionably face-framing strands of hair that had somehow once again liberated themselves from my workmanlike low bun” Acting. Student. If there is someone who a book chronicling the rise and fall of “The Method” is specifically for, it is me.

The indoctrination into the Adler technique, as it was always called—not “Method,” we turned our noses up at any mention of “Method” before gleefully telling stories about all the deliciously acid things Stella had said about Strasberg—included reading Adler ’s The Art of Acting, which begins with a preface from Marlon Brando commending Adler for not lending herself to “vulgar exploitations, as some other well-known so-called ‘methods’ of acting have done.” Yes, a Shyamalanian twist: Brando vehemently opposed Strasberg’s Method, despite being one of the actors most commonly associated with it, due to a lack of clarity surrounding the factions into which the lowercase-method’s early practitioners split. The method was the child of the Group, but as the parents bickered, they each left the artistic home of the Group behind, taking with them, à la the Judgment of Solomon, whatever chunk they found most useful. Gruesome? Sure, but as The Method re-minds us at almost every turn, theater can be a bloody business.

“Stella challenged Lee openly,” actor Phoebe Brand later said. “It was not done, you know. Lee was really an authority and we all thought he was God.” Brand, one of the longest-lived Group alums, is perhaps most frequently mentioned today as one of those blacklisted when Elia Kazan named names before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1952. Two decades prior, though, she was the prized ingenue of the Group and namesake of the “Fuck Phoebe Club” (comprised of male Group members vying to bed her). Butler does not shy away from depicting the male chauvinism that has become nearly synonymous with the Method, and in sharing this detail about the early days of the Group, he presents a harbinger of the more overtly horrifying tales of sexism associated with Method acolytes.

Misogyny is not necessarily baked into Method techniques, but it heavily influences who is classified as a difficult genius, iconoclast, or “Hellraiser,” and who is branded as more trouble than they’re worth. Butler’s consideration of “female Brando” Kim Stanley helps color in the why of the common misconceptions that make the pop-cultural avatar for Method actor “a male actor who wants to do The Purge in real life.” We hear so much more about “difficult” male Method actors because badly behaved male actors can achieve and maintain megastardom that lands them in newspapers and magazines; female actors with similarly destructive impulses have rarely been afforded the same luxury, regardless of talent.

In assessing the work of the operatic soprano assoluta Maria Callas, Italian music critic Eugenio Gara invoked a Chinese proverb: “who rides atop the tiger can never get off.” The aphorism is just as applicable to similarly preternatural dynamo Stanley, who was revitalizing her own art form during the same period. Callas’s contemporary Graziella Sciutti once said the diva confided in her mid-performance, “You know, every time I go out there, it’s like they are waiting to get me”; as one’s legend grows, so, too, does the number of people going in with arms folded claiming not to see what all the fuss is about, and this was certainly the case when Strasberg’s Actors Studio took its production of The Three Sisters across the pond. It is difficult to maintain the sought-after level of transcendence in performance without that perfectionism and dissatisfaction curdling into behavior that is unsustainable, and Stanley’s increasingly outrageous demands behind the scenes (and self-indulgent choices in them) contributed to catastrophe in London. The Brits, having long rolled their eyes over the head-shrinker hokum de rigueur in America, certainly did go in “waiting to get” the Studio, but the Studio, exemplified in many minds by the mercurial Stanley, provided plenty of vindicating evidence that the emperor was streaking across the Aldwych Theatre stage. The production took a beating from local audiences and press alike, and its previous glowing reviews from the New York run seemed to confirm the view that America’s obsession with the Method was merely the placebo effect of snake oil on the unsophisticated. Stanley never acted onstage again.

Butler writes with such awe, compassion, and conviction about Stanley that despite having only seen a few of her performances, I felt deeply connected to her artistry, cheering her triumphs, empathizing with her struggles, wincing at her failures. That he achieves this effect not only in his portrayal of her but also with the cavalcade of characters both famous and forgotten in The Method is nothing short of extraordinary. Every vignette springs from the page just as the actors in the Group’s breakthrough production of Waiting for Lefty leaped from their chairs to breathe life into a scene. As an author, Butler accomplishes what the Method’s devotees sought to do in their performances, bringing color and dimension to figures who might have been boxed into archetypal roles (omniscient godhead or exploitative charlatan) and presenting them to us in all their brilliant, infuriating complexity. The scope of the book is sweeping, the figures entering and exiting the narrative often larger-than-life, but each quote and anecdote Butler chooses to include draws them close enough to touch. When he tells us of how, after the catastrophic pre-Stanislavski premiere performance of The Seagull, Anton Chekhov softly agonized, “The author has flopped!” it’s impossible not to recognize that despair in ourselves. It is also impossible, then, if one is currently in the throes of their “flop era,” to not feel even a hint of perhaps long-dormant hope that the dam might eventually break. There is no shortage of spectacular bombast throughout The Method, but the inclusion of this one small quote, contextualized by all the great work Chekhov would go on to do and all the great work he would inspire long after his death, is a quiet miracle.

A few minutes into Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, the ennui-plagued country doctor Astrov asks of elderly nursemaid Marina, “What will they think of us, in a hundred, two hundred years, those who come after us, who we’re clearing the road for today, will they have anything good to say about us? Nanny, will they even remember us?” It is at about this point in a recent viewing of André Gregory’s adaptation Vanya on 42nd Street that I realized Marina was played by none other than Phoebe Brand. Four decades after HUAC, six past the “F.P.C.,” Brand delivers Marina’s reply with a twinkle in her eye and a beatific smile: “The people won’t remember . . . but God will.” Past, present, and future intertwine; Chekhov’s work with Stanislavski cleared the road for Phoebe Brand and the Group, who cleared the road for those like Brand’s Vanya costar Julianne Moore, who clears the road, who clears the road, who clears the road. The road is endless. The beauty of this moment is also at the heart of The Method: we are the fallible, forgetful people, but in the moments when we choose to remember, we can be divine.

The author has not flopped.

Natalie Walker is a performer and writer in New York.