IN THE UNRULY ANNALS of twentieth-century American art, Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009) carved a quiet place for himself as a chronicler of clapboard fronts and windswept fields in the shadeless stretches of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and, later, Maine. The artist imbued his portraits and landscapes with a kind of sacred plainness, his drybrush paintings capturing the specific dust-in-the-water melancholia of Middle America.

For a painter so steeped in realism, Wyeth cultivated quite a mystique about himself. An aura of death permeated his paintings, rendering them at once fragile and leaden. Mortality figured literally in works such as Burial at Archies, which was executed in the early 1930s, and the 1945 canvas John Olson’s Funeral. At other times, the painter turned to metaphor. In Pentecost, 1989, the wind gently buffets the fishing nets along the shores where a young girl drowned, while Trodden Weed, 1951, refigures the painter’s anxieties after a lung surgery gone awry.

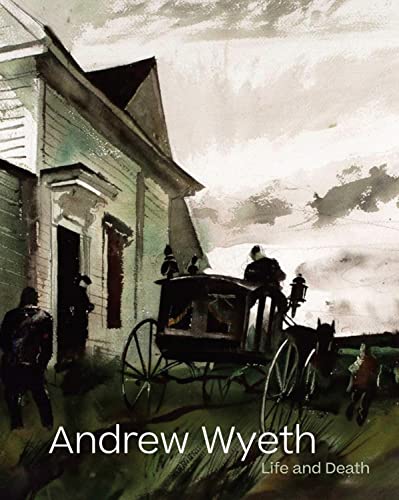

But there was another side of Wyeth. A man unnervingly obsessed with Halloween, he acquired an antique hearse and used it to stage a mock funeral one Fourth of July. This macabre streak reached a crescendo in Dr. Syn, an exceedingly curious 1981 tempera self-portrait of the artist as a skeleton, decked out in an ornate naval jacket from the War of 1812. A birthday gift for the artist’s wife, Betsy, the painting reads like an elaborate inside joke, and yet when he created it, Wyeth had to know this peculiar representation would outlive him.

Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death surveys these and other paintings, including a recently recovered body of sketches made in the early 1990s. Spurning both the showmanship of Dr. Syn and the tender, surrealist-tinged hope of regeneration edging Christmas Morning, 1944, this “Funeral Group” takes a stark, unflinching view of death. The studies plot Wyeth’s own funeral, his body laid out in a simple coffin flanked by family and neighbors. There is no rending of garments among the mourners. Betsy, Helen Sipala (a neighbor who photographed the artist for his self-portrait as a corpse), and Helga Testorf (the burly blond who would become Wyeth’s studio assistant, model, and, it is speculated, something more intimate) all look down with the same weary resignation, while the specter of a transmission tower looms over them, a grim (but patient) reaper.

With little documentation in its wake, the “Funeral Group” took quite a bit of detective work to decipher. The catalogue features research from Karen Baumgartner, Alexander Nemerov, and Rachael Z. DeLue alongside exhibition curator Tanya Sheehan’s condensed history of American artists reckoning with their own mortality through self-portraiture. The exhibition put Wyeth into direct dialogue with some of his more conceptually minded contemporaries, including David Wojnarowicz, Janaina Tschäpe, and Andy Warhol—oddly, no stranger to Chadds Ford as a friend of Wyeth’s son Jamie. Unlike the other Andy’s Skulls screen print, 1976, Wyeth’s lost studies refuse to relegate death to the world of spectacle.