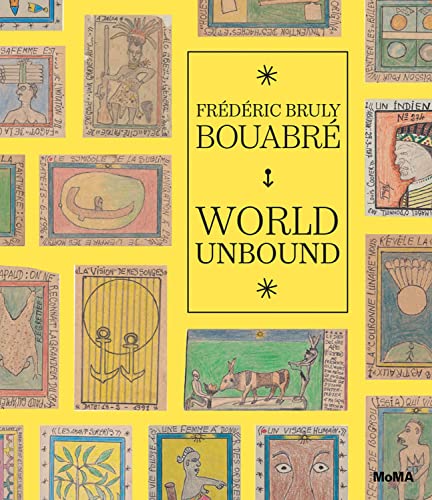

ONE DAY IN MARCH 1948, a twenty-five-year-old clerk in the French colonial administration in Ivory Coast experienced a transformative vision. He reported that the sky opened and “seven colored suns described a circle of beauty around their ‘Mother-Sun’” and that he was then called upon to be “the Revealer.” This divine command would set Frédéric Bruly Bouabré on an investigative path deep into the folklore, language, and religion of his people, the Bété, an undertaking that produced voluminous texts and thousands of drawings, all aimed at elucidating his cultural heritage as the foundation of a universal cosmology. Accompanying a current show at the Museum of Modern Art (New York), this volume presents two serial works—Alphabet Bété (1990–1991) and Knowledge of the World (1987–2008)—whose titles proclaim their vast ambition. Each of the 449 colored-pencil and ballpoint-pen drawings on cardboard that constitute Alphabet Bété illustrate a single monosyllable in the Bété language. The enumerated images depict familiar activities (lighting a fire, chopping down a tree, rowing a boat, copulation) and common objects (chair, leaf, snake, spear) that illustrate the handprinted syllable. Undoubtedly some linguistic proficiency would enrich the connection between, say, a saw and the syllable “si = ci,” but the relationships still prove enticingly cryptic for the uninitiated. Thirty similarly devised drawings comprise Knowledge of the World, an encyclopedia-like attempt to document the range of human experience, from being disfigured in a war to seeing a butterfly, from “une divine signature” to wine gourds.

The taxonomic scope of these projects, especially Alphabet Bété, predicates a large number of images, many with only minor variations from the others. The distinction between two sequential pieces—Fé and Fê—is represented by the difference between a female figure with an axe chopping two logs and the same figure, same posture, chopping at the air. These near repetitions, along with Bouabré’s consistent palette of soft greens and yellows, establish an almost incantatory rhythm that rewards viewing multiple pictures at once. Immersion is clearly invited, and the resulting effect is akin to listening to poetic declamation.

Francophone Bouabré annotates many drawing with a description that often extends around the full margin of the rectangle. The caption “Le symbole de la sublime navigation á partir de l’empire des morts” (The symbol of the sublime navigation from the empire of the dead) surrounds a solitary figure in a comma-shaped vessel. Reading the sideways and upside-down text requires an angled attention that might lead the viewer to suspect it’s a ploy to encourage closer engagement with the artwork. But Bouabré’s intent is far from canny; rather he explicitly seeks to explain his depictions. In a film on display at MoMA, he declares, “Writing is what immortalizes. Writing fights against forgetting.” The endeavor is Blakean—to reveal the world in a grain of Bété sand—and the artist’s unflaggingly inventive imagination is well suited to the task.