I SUSPECT EVERYONE WHO KEEPS A DIARY of wanting it to be found. What you write depends on what you allow yourself to see, and how you want to be seen. It’s a common thought—Susan Sontag famously said, “A journal or diary is precisely to be read furtively by other people”—and points to a basic contradictory principle of the unconscious. Self-admission is always tied to self-betrayal.

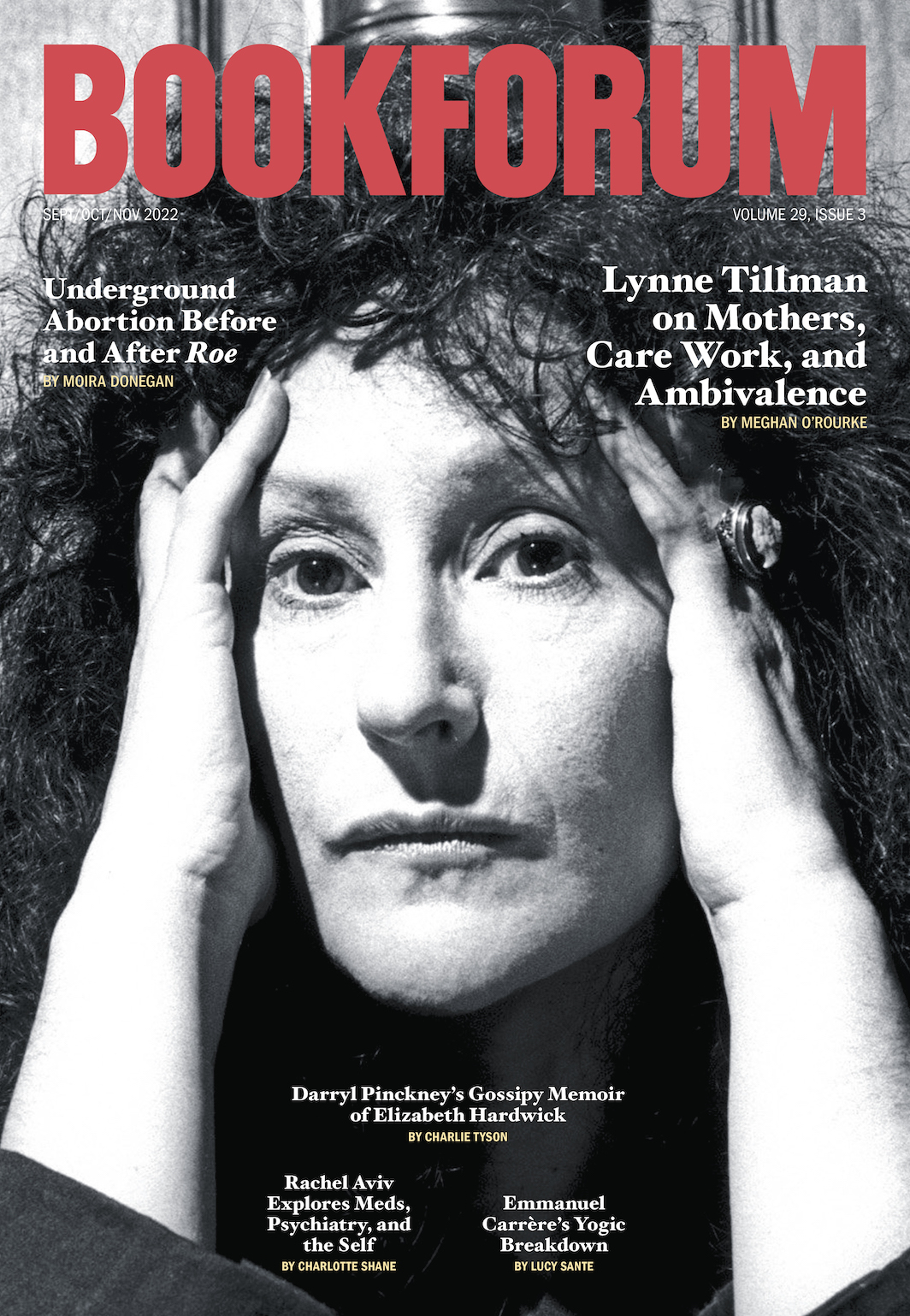

Anne Truitt began keeping a daily journal in June 1974. Her ostensible aim was to “record my life and see what happened.” It may have had more to do with steadying her mind. Her decision followed two retrospective exhibits that had left her feeling “crazed, as china is crazed, with tiny fissures,” as she writes in Daybook, released in 1982. Seeing her work in space—the radiant sculptures, the taut drawings—revealed what she had transmuted within them. Like a one-woman embodiment of Persona, she suddenly perceived herself as fundamentally split: on one side, the artist, the other, the “rest of me,” with the artist playing the antagonist to the person. The artist had “deprived” her of herself; “ravished the rest of me and got away scot-free.” (That Anne Truitt is fifty-three years old before she realizes she is her own adversary seems lucky or deluded, depending on my mood.) She begins to sound like someone on the stand. “I had the curious feeling of being brought personally to justice.” Her solution is to let the artist speak.

The more people talk the more they will reveal contradictions, or just themselves. Midway through Daybook—which was followed by the journals Turn, Prospect, and now the posthumous Yield—Truitt draws a parallel between ecdysis and keeping a diary.

I once watched a snake shed his skin. Discomfort apparently alternating with relief, he stretched and contracted, stretched and contracted, and slowly, slowly pushed himself out of the front end of himself. His skin lay behind him, transparent. The writing of these notebooks has been like that for me.

Arresting image, but it’s less the tidy metaphor than Truitt’s obsessive return to snakes, as signs of death and evil at times of narrative shakiness, that interests me. That’s what diaries show: something the mind can’t shed. In Prospect, Truitt invokes a more revealing analogy: “This notebook that I am writing is a castle that I can take with me.” The enemies this imaginary fortress provides protection from remain ambiguous.

She introduces the diary/castle parallel with an ex post facto rationalization: “I am not without my defenses, however—my private castles.” It’s a concession to her own writerly intentions: less an explanation of her life than an attempt to shape perceptions about it. The texture of Truitt’s writing makes more sense in this light. The journals read less like diaries—propulsive, emotional, repetitive—than public addresses. But if they are written with an audience in mind, then the overdetermined signs and slips seem like clues left out in plain sight.

Facets of Truitt’s childhood explain a certain austere remove. The firstborn in a “sad family”—her father an alcoholic “crippled by his frivolity,” her mother a “delicate” Boston blue blood—Anne grows up solemn, severe. Stiff-pigtailed. Her brushes with freedom have the feeling of accidents. She returns to her unhappy past frequently, trying to sift out the good and inevitably rehearsing the bad. Her parents fall ill and Anne, at twelve, takes charge of the household. “Under this pressure,” she writes, “a certain crystallization took place in my character.”

She receives a degree in psychology from Bryn Mawr in 1943, and then volunteers with the Red Cross. Throughout the war she works at a psychiatric lab in Boston, treating soldiers suffering from battle fatigue. She sees psychology as “a position from which I could engage in battle” until, one day, following a routine input test, the “situation [flashes] into a lie” and she abandons course. She writes poems and short stories, studies at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Washington, DC, and begins making work. In 1947 she marries the journalist James Truitt, and the family (she soon has three children) zigzags between San Francisco and Washington. She works daily in the studio, but makes the first work she “respects” in 1961, at age forty. The past works—“expressionistic, declamatory, rhetorical”—she destroys. (Truitt’s reference to herself as a “bit player, more moved than mover” begins to seem, at a point, like a story she needs to tell herself.)

Her sculptural form, once found, doesn’t waver: heavy freestanding sculptures austere in structure, expressive in color. She wanted to take the paint off the wall and see light on an object, to watch it for some time. Kenneth Noland, a friend from her student days, recognizes the power of this work and starts making introductions. Her first exhibition, at André Emmerich Gallery in New York, comes at forty-one, a midlife beginning. Three years later, she is one of the few women featured in Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, the landmark exhibition that served to introduce Minimalism as an antidote to Abstract Expressionism and Pop art. In 1964, the family moves to Japan, where James is appointed Far East bureau chief for Newsweek. The move cuts short her momentum. Despite key support (Walter Hopps and Clement Greenberg were her champions) and institutional acclaim, her works rarely sell, and interest flags as Minimalism falls out of fashion. In 1971, she divorces James, who is an alcoholic and mentally ill, and takes on full custody and financial responsibility for their three children.

It’s from this vantage—a single mother living in Washington—that Truitt begins writing. Her relative remove from the New York art world, cut off from her peers, partly explains the journals. She was writing what she might otherwise have said in conversation.

But if what Truitt wants is to be understood, then she also wants to set the terms of that understanding. Her editing process attests to a desire for narrative control. First, Truitt would record herself reading her handwritten journals aloud, revising as she spoke. This preliminary manuscript would then be further edited, first by Truitt, then her editor. Their reasoned, steady tone is in keeping with this process, which supports standardized flow over confused excess. The portrait they provide of Truitt is, like most journals, inherently skewed, a distorted self-portrait. Her control over the process also hearkens the question of what she is striking from the record. There’s always a reason to leave things out; to correct earlier misjudgments; to present yourself in a better light, a spiritual cosmetic gloss; and to protect the feelings and reputations of the living. Or they’re unconscious omissions, the things we can’t say to ourselves.

One of the graces of her journals—Daybook in particular—is the revelation of the artist’s day-to-day. Truitt communes with herself about the work she is making and intends to make, and discusses problems of color and form, material and meaning. The most memorable passages draw on her precise eye: Japan from above is “wrinkled-prune land, purple in an apricot-violet mist of evening light”; the telephone receiver is “shaped like a black tulip held to her ear.” The notebooks throw light upon her intentions, works, and methods as an artist, while also offering a psychological picture of artistic production from within. Her notes about the nerve needed and compromises made in order to be an artist act as both warning and encouragement for younger artists.

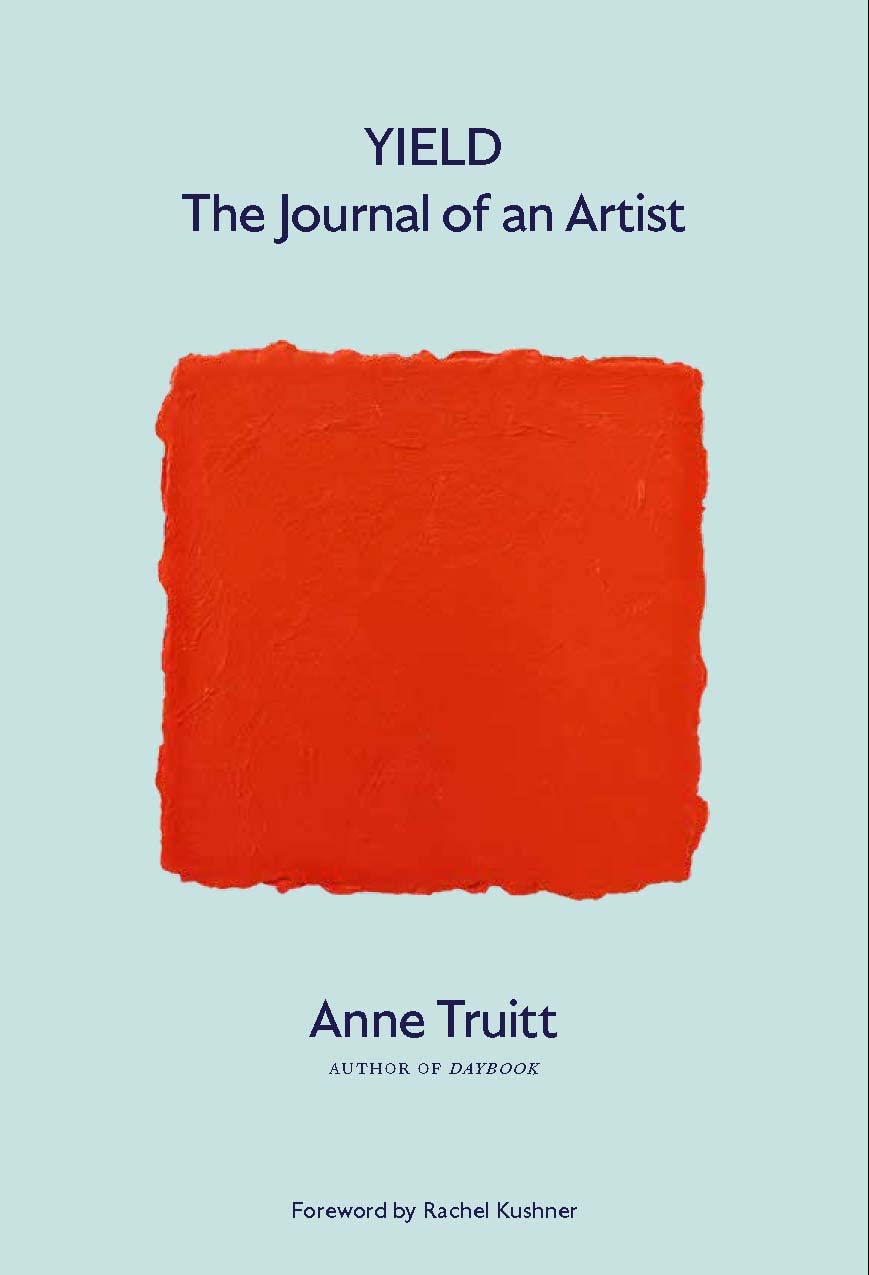

Yield brings together notebooks from winter 2001 to spring 2002, and follows the same unadorned, self-seeking path. Here she tells what it is to be an artist at eighty and to still be working. All of Truitt’s journals are death-haunted, but these notebooks, written shortly before her own death, have the distinct emotional charge of someone coming to terms with their mortality. She treats age as an experience different from others and detects the gradual stages toward death. The entries are less episodic, more fragmentary and associative. Time becomes voluminous; the past increasingly “folds into the present.” She also begins to write about people and events previously unmentioned.

In her early years in Washington, the young Truitt shared a studio with Mary Pinchot Meyer, a fellow struggling artist and society wife in the Georgetown milieu made up of spies, policy makers, and journalists of Kennedy-era America. Meyer was blond, vivacious, and outspoken against the CIA. She was also having an affair with John F. Kennedy. In 1964, one year after his assassination, Meyer is shot in broad daylight in Georgetown.

In the year before her murder, Meyer, of a prophetically paranoid mind, had asked Anne to take possession of her diaries “if anything ever [happens] to me.” Anne was to keep the diaries and show them to Meyer’s son at twenty-one. The night of Meyer’s murder, Truitt, then living in Japan, called James Angleton, the CIA’s head of counterintelligence, to find and “take charge of” the diaries. From there accounts differ. Angleton was with Benjamin Bradlee, Washington journalist (also, coincidentally, Meyer’s brother-in-law), who might have alerted Cord Meyer, Mary’s ex-husband and a CIA agent. In either case, Anne made the ask and the problem of the diary was “resolved.” (The CIA destroyed it.)

Truitt, in her prior journals, had sketched the loosest portrait of Mary. She is described as a “dearly beloved friend”; “an acute judge of masculine character”; “murdered while walking along the Potomac River.” In Yield she remembers that she and Cord and James and Mary had all been, for a time, “in utero together, aligned in a short stretch of time.” Four months before her diaries come to an end, she considers speaking about Meyer and the fallout. She writes, “I may—only may, still turning the matter over in my mind—be coming to the feeling of responsibility to experience that incurs moral action.” It can take a lifetime to land on “may.” Truitt’s moral action remains open-ended.

I read about Meyer’s diaries and Truitt’s role in their destruction at a friend’s. “But Anne Truitt is so . . . respectable,” I said. “Isn’t calling the CIA,” she said, “exactly what a respectable woman would do?”

Janique Vigier is a writer living in New York.