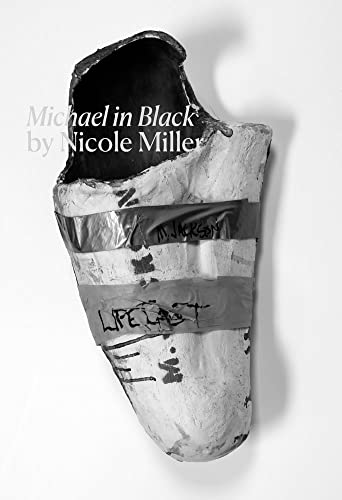

NICOLE MILLER’S Michael in Black is a monograph-as-moodboard, dedicated to the artist’s eponymous bronze sculpture of Michael Jackson kneeling, which was produced from a mold live-cast for a scene in the 1988 video anthology Moonwalker. There’s a sour-patch prescience to the depiction of the superstar—known for his celestial glide—in such a humbled stance, his arms truncated at the wrists. There’s a line in John Jeremiah Sullivan’s canonic 2009 essay on Jackson where the writer hails the pop singer’s body as “arguably, even inarguably, the single greatest piece of postmodern American sculpture.” Miller’s version has none of this fanfare. In her searing essay, “A Doctrine of Love,” Hannah Black likens the portrait to an insect on its back, little legs waving in the air. Or, just as savagely, “a sad cousin”: “There is so much to condemn [Jackson] for, but he appears before us, punished in advance.”

What follows is a patchwork of interrelated excerpts all loosely orbiting around what Miller describes as the urge to “[consume] ideas of people.” Reprinted texts retain the formatting of their original publication, so that the paperback prettiness of Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous contrasts with Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “Observations on the Long Take,” a meditation anchored in the footage of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, here petrified in the typeface of OCTOBER magazine. Interspersed are images, including Arthur Jafa’s Mapplethorpe-esque ode to MJ; Lyle Ashton Harris’s self-portrait, wary-eyed in bed under an oversize poster for Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio; Heji Shin’s headshot of Kanye West tinted in apple-cider shades; and a photograph of Zoe Saldana, famously miscast as Nina Simone for the 2016 biopic Nina.

Punctuating these contributions are starkly shot photos offering different perspectives of Michael in Black. In one close-cropped photo of the mold, a tiny pole is propped up under the chin. There’s an obscene intimacy about this appendage; it appears less as support than as some kind of absurd presumption of possession, like a flag planted on the moon. Jackson was exactly the kind of figure others like to pin their claims on, but he also had a way of slipping out from under those claims. As Black writes, “Now that we are grown up, we handle the songs more cautiously. Now we know as well as he did, and did not, that the world—law, money, the state, the street, the morning—beats love like paper beats rock: counterintuitively and with an enveloping gesture.” But it wasn’t all love, was it?