What does it do to us to lose someone? What does it do to a family? Can we separate our private devastation from the broader world that created the conditions under which we suffer loss?

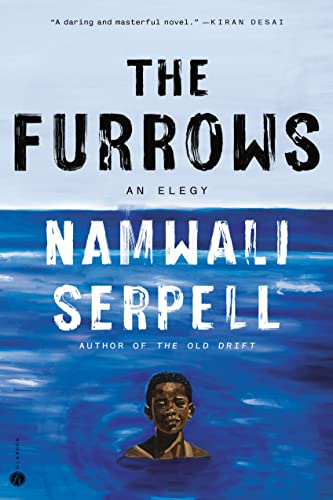

These are the questions that haunt Namwali Serpell’s The Furrows (Hogarth, $27). While her previous novel, The Old Drift, is a sprawling epic that manages to make the colonization of the place now known as Zambia something we feel, The Furrows is a more intimate book, yet the questions at its core are no less troubling and demanding. The story at first appears to be straightforward: it’s about a big sister who lost her little brother far too young, the blame and anger and fear that splinter the family, the people who are pulled in to and pushed out of their orbit, and American racism and the petty and large violences it enacts. Yet nothing about this book is straightforward, not even the death at its core. The novel is difficult the way grief is difficult, recognizable the way a lost loved one’s face sometimes seems to appear on the face of a stranger, unsettling the way the griever pushes away the people they love and latches onto people they just met because they seem to understand. The splits in the narrative seem to echo the splits between the family members and the impossibility of a single story. I spoke with Serpell about family and her fiction-writing process, the power of books that aren’t easy to read, and what Freud gets right—and wrong—about grief and loss.

Sarah Jaffe: In an interview, you told the New York Review of Books that you finished this book in 2014 and put it in a drawer. Can you tell us the story of this book and how it’s changed since you pulled it out of that drawer?

Namwali Serpell: I had conceived this book, as I often do with my projects, in one fell swoop, after a dream that I had in 2008. And I wrote it for six years alongside writing my first academic book, Seven Modes of Uncertainty. Those two books were twins in their creation. I like to say that in the drawer it was collecting shadows. One of the big shifts in the novel is that a certain kind of darkness crept in, especially in the second half, which had originally been a bit more noir, which is to say a bit more atmospheric, in the grays. It’s very much a San Francisco novel but also a Baltimore novel. And they both have a strong noir tradition. In the revision, it took on much more of the darker tones of Edgar Allan Poe. When I first started it, I had not read any Elena Ferrante. By the time I finished it, I had, and her books inspired the largest revision—to change the novel’s narration from the third person to the first. I decided to immerse the reader in the perspective of three main characters, with an eye toward unreliability, an eye toward internal fracture and schism, rather than what I think some early readers assumed was a kind of multiverse objective picture of a world with multiple possibilities.

The book that it made me think of was Beloved—the way you’re not sure who this ghost is, to what degree she’s real. When I began reading The Furrows, I thought, “This is just the straightforward story of what happened to the little brother, Wayne.” The second time the story of what happened to him is told I thought, “Wait, what?” And then the third time, I finally thought, “Oh, I get it!”

That’s why I had to have exactly three. I think repetition is a very delicate tool for narrative. If you underdo it or overdo it, you get very different effects.

We’re used to doubles in fiction and cinema. But you have triples here: three repetitions of the story and three characters who we’re not ever sure are three separate people.

I think the double is a very powerful figure in literature, particularly genre fiction. For me, the double is always triple. The recognition of the two is itself a three, is meta—the perception of the very fact of the doppelgänger makes it a three.

The way that the family splits, and the way that the characters themselves are split, really captured the experience of grieving. What is it about grief and loss that ends up being so splintering?

It’s definitely the experience I had when my sister passed in 1999, when I was eighteen and she was twenty-two. The way that affected my family, partly because it was quite a shock—she was so young—really influenced the way I conceptualized grief. Then, between the time of finishing the novel and my decision to go back and revise, my mother passed. The difference between those two mourning processes, but also the similarities, really sharpened for me a sense of how particular it is to lose a child in a family. One of the things that really struck me when my sister passed was how different our memories of her were. We all had different interpretations of what happened to her and why, and how each of us was involved or complicit or had tried to help her or prevent it.

I wrote an essay called “Beauty Tips From My Dead Sister,” and I included some photographs of me and her. The skew in memory is so intense that my eldest sister swears that one of those pictures is not of my late sister, but of her. With the other memories, where there’s not even a photograph that can be contested, there’s nobody to verify what the truth was. But how strange it is: it’s not that we have conflicting interpretations of something that exists, but of something that is lost, of an absence. And that to me is very haunting, especially because it is unsolvable.

The character I was most fascinated with was the mother, Charlotte, and her stuckness. These questions of mourning and melancholia, to be Freudian about it, are such complicated questions.

I don’t know if I agree with Freud’s distinction between mourning and melancholia, but there’s a certain line in that piece that I was just revisiting the other day: “The shadow of the object fell upon the ego.” Because you can’t do anything about having lost someone, and you’ve attached yourself to them, the shadow of them falls on you. You internalize that loss, and it becomes a shadow inside you. I find that so haunting and right.

He says the ego wishes to incorporate the lost object into itself, and the method by which it would do so in the oral or cannibalistic stage is by devouring it. That sense of rapacious hunger is influential to my depiction of both Charlotte and C. It manifests for Charlotte in the building of this foundation—she revolves her life around it. And for C that devouring hunger turns, I think, uncomfortably towards the sexual.

The father refers to the foundation as Charlotte’s business—and there’s the line, “The presumption that made her think to collect dues on grief in the first place.” In terms of things that we might think of as “bad” mourning, charging for it seems up there.

I really strongly believe in rituals of mourning. I think that they are indispensable in a lot of ways and we’ve lost track of that. During the pandemic, people have been barred access to those rituals, which is one of the greatest tragedies of this horrible time. In the twentieth and twenty-first century, a lot of our predisposition toward human ritual has been converted into our rituals around work, around labor. This is how we spend our days. So paying dues on grief, that’s also paying tithe. There’s a kind of transference, I think—especially because I make it clear that Charlotte is a lapsed Catholic—towards treating this as her way of ritualizing her mourning. I think I would probably put some pressure on the notion of bad mourning and go against Freud, in the same way that I seriously object to his distinctions between different kinds of orgasm, etc. I don’t think there is such a thing as bad mourning because I don’t think there’s such a thing as good mourning. It’s just mourning. That’s one of the reasons that it felt important to depict the family members having different ways of dealing with their grief, because the father can castigate Charlotte all he wants, but he’s out there hunting for this man in a windbreaker when it’s very unclear whether that man had anything to do with Wayne’s disappearance. I think there’s a kind of shaming that we do of different kinds of mourning. Good or bad, fulfilled or unfulfilled, resolved or unresolved. In the end it’s almost too much to ask when you’re already dealing with such horrible loss that you also deal with that loss in the best way.

One of the places that I push back on that same Freud essay is the idea that there is work to mourning. We do see these people in your novel trying to work at it. But there’s no work you can do.

I just read this very interesting essay, “Drift as A Planetary Phenomenon” by Bronislaw Szerszynski. It points out that we’ve lost, in the English language, what in Latin and Greek is called the middle voice, which is a kind of verb that is neither passive nor active. There’s a couple of traces of it. We have the word float, the word drift. When you float, are you being floated or are you yourself floating? It’s somewhere between the two.

Mourning has that quality. It’s not something that you do exactly nor is it something that is done to you. It’s somewhere in between. And so, “work” is too active a notion to apply to something that really sits in the middle of our spectrum of agency.

The image of the furrows is of being stuck in water that is moving all the time, and you can’t escape—that’s one of the reasons that image works for me. You’re in a swell or a spell that feels like you’re moving forward, but it also feels like you’re endlessly being cast back into grief.

The second part of the book, where you switch the narrative to Wayne and Will, brings the person being mourned back into the story.

Yes, I really wanted to draw my reader into this story of loss and to give no real reasons. There’s no spelling out of why it’s a tragedy that this boy dies or goes missing. It’s just a loss of a brimming, vibrant life. I wanted readers to feel that and how it impacts this family before I trace what that little boy might have become, the violence to which he would have been subjected to in various realms of his life, whether it’s the violence that the boys inflict on each other or the violence of the state that confuses them for each other.

I wanted to make the reader realize how often our compassion for others is contingent on who they are—or who we think they are. That little boy that got lost could have been one of these men who are subjected to horrific surveillance and violence. And it’s almost a reversal of the effect where a young Black man, unarmed, gets killed by the police. Eventually—maybe two, three months down the line—we get baby pictures. I wanted to make the reader just feel that it is always someone who once was a child and very often it is just a child, as in Trayvon Martin’s case.

You wrote an essay a while back on Toni Morrison and difficulty. It’s interesting to sit with a book like this, because you have to be OK with there not being answers.

In Seven Modes of Uncertainty, part of what I was trying to figure out is why uncertainty was so painful for me in my life, but so rich and interesting to me in literature. A lot of what I’m probing there is the way that literature is experiential. You don’t just absorb information or facts about what happens, you’re also engaged in a temporal experience that moves you both emotionally and intellectually.

My thinking about the purpose of literature as a critic helps bolster my impulses as a fiction writer. I’m trying to render an experience and move away—as much as possible—from a passive-reception model of the reading experience, where you’re just fed information. And that entails making the reader come forward and participate in the co-creation of the text. As Morrison puts it, you have to have gaps, spaces for the reader to step in. There’s something connected in my mind between literary uncertainty, literary difficulty, literary experiment, and this onus on participatory experiential reading. Even if that experience is one of confusion or frustration, it’s still getting you to feel something. Each of my novels comes to me in the genre or structure that it needs to be. And sometimes, as with grief, which is difficult, the structure is difficult. I understand the risk, but I think there’s enough resonant sentiment in the discourse, in the culture, about the uses of difficulty for me to feel like I’m not alone. I trust my readers to follow through, to get it, to interpret.

A condensed version of this interview appeared in the fall issue of Bookforum.

Sarah Jaffe is the author of Work Won’t Love You Back: How Devotion to Our Jobs Keeps Us Exploited, Exhausted, and Alone (Bold Type Books, 2021).