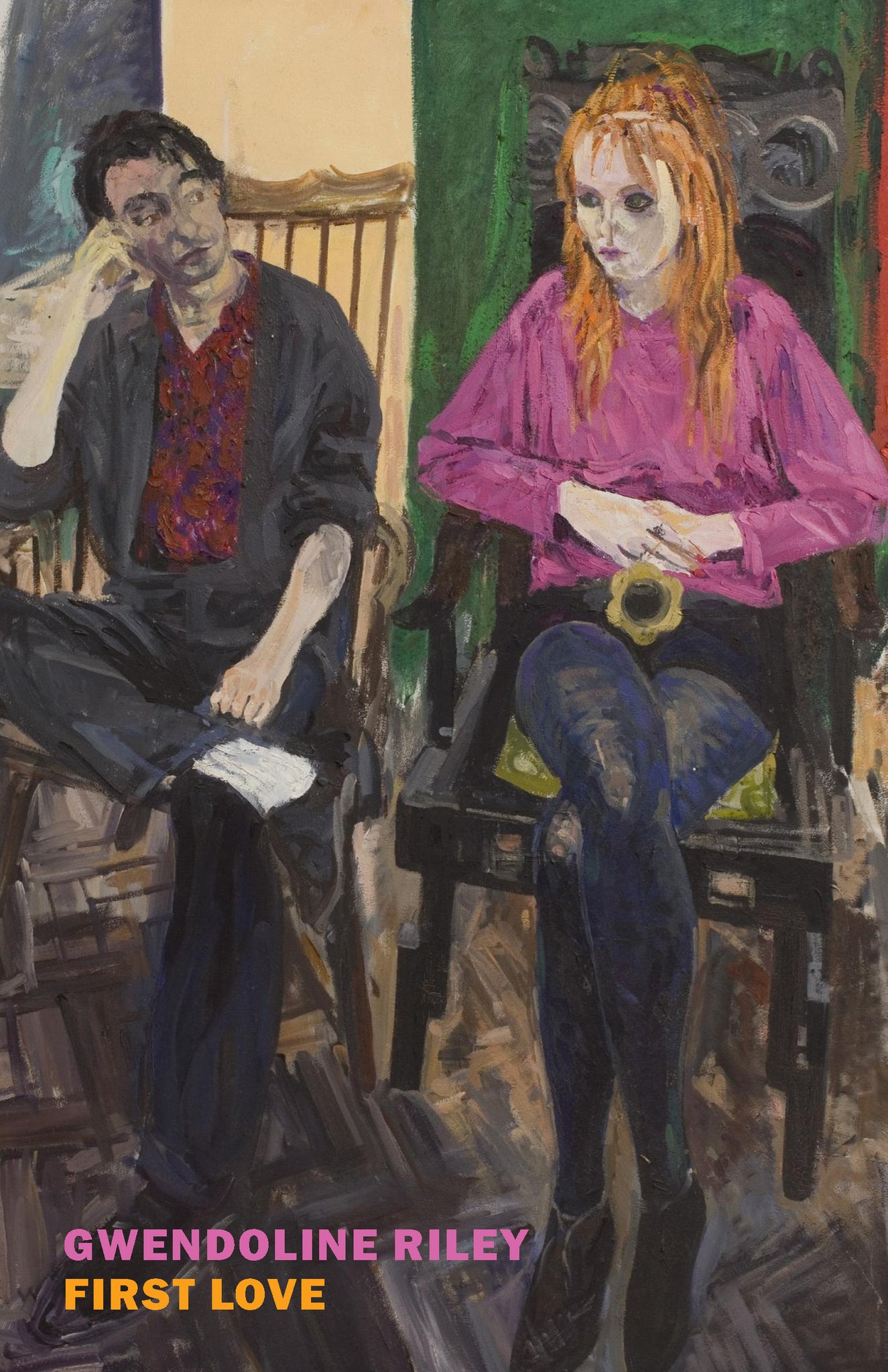

THERE ARE A LOT OF OLD FLAMES in Gwendoline Riley’s 2017 book First Love. The novel begins where so many end—in marriage, with its protagonist Neve moving into her husband Edwyn’s flat in London. What looks like the prelude to the sweet life—two lovers easing into domestic settlement—soon turns sour. There are pet names, and then there are “other names, of course.” On page two, we learn that Edwyn once called Neve “a fishwife shrew with a face like a fucking arsehole that’s had . . . green acid shoved up it,” among other things. It only gets more rancid from there.

Neve is thirty-three, around the age many literary heroines get married these days, though that hardly makes her plot any more resolved, more certain, or happy. The novel is narrated from her ruthlessly anxious perspective, oscillating between scenes from her childhood—where we often find Neve trapped in hostile exchanges with her abusive parents—to scenes with her ex-lovers and finally her husband. “Finding out what you already know. Repeatingly,” reflects Neve during a fight with Edwyn, “That’s not sane, is it?” But this wry self-awareness hardly stops Neve from repeatedly finding the same things out. Edwyn is considerably older, and his story arguably even more gothic. He is often housebound, incapacitated by an unnamed disease. One of the reasons he marries Neve is that“everyone named in his previous will [was] dead.”

First Love is the fifth novel by Riley, who, at the age of forty-three, has already published six. If you haven’t read any yet, it’s probably because until recently her work has not been readily available in the US, though New York Review Books will reissue her latest two this fall. Alongside First Love, they will also release Riley’s most recent novel, My Phantoms (2021), which charts a different kind of first love: the tortured relationship between the narrator Bridget and her mother. Yet even here, the story is still one of curdled family romance. The ghosts haunting First Love and My Phantoms are comprised of the usual suspects: megalomaniacal fathers, mewingly needy mothers, and the children who cannot help but repeat their mistakes. It’s a classic psychoanalytical model—one that is also intimate to the novel.

Born in London, Riley grew up with her maternal grandparents in the northwest of England after her parents’ divorce—a period she recalls being “horrible” and during which making up stories became a form of retreat. After graduating with a degree in English literature from Manchester Metropolitan University, Riley worked part-time in a bar while writing; she considers herself estranged from her parents.

Yet if Riley keeps her parents at a distance in real life, she appears to speak to them endlessly in her fiction. Since her 2002 debut, Cold Water, published when she was twenty-two, the writer has circled around a consistent set of themes—love, misogyny, marriage, divorce—with increasing insight and brutality. Her slim novels are all narrated from the chilly first-person voice of lonely, moody heroines, often the daughters of ineffectual parents. Riley herself has acknowledged the similarities across her work, including the autobiographical resonances with her protagonists. First Love and My Phantoms, which might be read as companion texts, mark a distinct maturation in Riley’s storytelling powers, despite—or precisely through—their compulsive repetition of the same old themes.

First Love is a book in which not much really happens, even as its emotional stakes feel increasingly dire. Riley is frequently compared to Jean Rhys, Albert Camus, or something akin to kitchen-sink existentialism, but her novels seem to share more with the stuffed, claustrophobic apartments of Barbara Pym novels or Harold Pinter plays. The mechanism of her plots is opaque, unfolding more through shifts at the level of atmosphere or tone than through characters acting and facing the consequences. It’s never clear how Neve and Edwyn meet or why these two people, “who’d always expected, planned, to live their lives alone,” finally decide to cohabit. Much of the mystery of First Love lies in why they insist on staying together. If Sally Rooney’s novels tell stories of “people who, over the course of several years, apparently could not leave one another alone” as the fulfillment of the romance plot, then Riley’s seem to narrate that same compulsion in the key of tragedy. “I was thirty-three and that was how it was,” concedes Neve after yet another fight with Edwyn, “Backed into this same wretched corner. Worse each time, in fact.”

Riley’s heroines initially appear to be at the perpetual mercy of other people, to a degree that suggests these bitter, brittle heroines might even derive some masochistic comfort out of being endlessly tortured. Neve and Bridget both recount horror stories from the aftermath of their parents’ divorce, especially around weekly visitations from their bullying fathers. As Neve recalls in terse sentences that convey their burdening effect: “For fifteen years, every Saturday, my brother and I were laid on to service him. To listen to him. To be frightened by him, should he feel like it.” In My Phantoms, Bridget describes her father’s “Saturday ‘access’ visits” in much the same way—something to be “weathered.” Or, as her mother would say: “There’s no point in provoking him, is there?” In a particularly gruesome childhood memory, Neve recalls her father telling her—in front of his male friend—“to go and clean up” in the bathroom, in reference to “two drops of dried blood, both tiny” under the toilet seat. Despite the familiar backdrop of the British novel—the creaky London flat, the decaying pubs, the sprawling motorways—Riley’s characters more often resemble feral animals, running on instinct and fear, than inheritors of Victorian domestic fiction.

Much of Neve’s childhood impulses persist in her marriage, though it’s less clear whether they’re survival mechanisms or simply the involuntary return of muscle memory. Edwyn is a misogynist, to be sure, but his viciousness toward Neve is also one she knowingly invites, precipitated by a history of abuse. Amid their ongoing fights, Neve considers how “it was both strange, and dreadful—I knew it—to feel that I was managing him, in a way.” This halting language, at turns exacting (“I knew it”) and equivocating (“in a way”), is exemplary of Riley’s prose, which frequently presents a strong thesis only to immediately turn in on itself. Riley’s narrators are so desperately self-aware, their defensive certainty frequently regresses back into uncertainty again. Her sentences cut to the chase, and then hedge, waffle, recede in rhetorical questions: “is it?”; “you know?”; “aren’t I?”

First Love ends in a scene of heightened crisis—will Neve finally leave Edwyn?—but also prolonged malaise, giving us perhaps the narrator’s sharpest glimpse into her own habits of repression and denial. Throughout the novel, Neve finds herself paralyzed by sudden crests of fear. The final pages of First Love are a tense tightrope act in which Neve’s sense of terror might finally break into clarity. But it’s one that seems so overwhelmingly total that her response is always finally to turn away.

When we reencounter these dynamics in My Phantoms, there’s a growing sense that the heroine’s masochistic tendencies have begun to turn outward. Bridget appears to have absorbed her childhood scripts so well as to continuously reenact them, as if on autopilot. “My mother seemed braced against an interrogation wherever we went,” she writes. Bridget’s mother Helen—or Hen as she’s ironically called—is something of a textbook narcissist, requiring a nontrivial amount of coaxing from her daughter. But it’s also Bridget’s refusal to see her mother beyond a generic type that keeps their relationship in a holding pattern.

My Phantoms is largely organized around a series of awkward dinner dates celebrating Hen’s birthday—a strange inversion of parental roles, where it appears to be the daughter’s duty to manage the mother. “My mother loved rules,” Bridget recalls, “She enjoyed answering questions when she felt that she had the right answer, an approved answer. I understood that when I was very small, and could provide the prompts accordingly.” Much of the novel is composed of dinner conversations where Bridget seems defensively geared to feed her mother the right, unthreatening lines—ones that might produce the approved answers. “That scrabble for combustible material . . . My instinct was that it was the best thing to do; that it kept something else at bay.” The thing being kept at bay, however, seems less clear to Bridget.

What makes these dinner scenes painfully stilted at the level of plot—of narrative progress—inversely renders them gripping at the level of psychic drama. Bridget’s unyielding evasion of her mother’s moments do not go unnoted by Bridget herself, who seems to recognize her emotional withholding as a form of cruelty. When Hen alludes to things her ex-husband used to make her do when they were married, Bridget responds by cheerfully compiling for her a list of potential therapists. “This great disowner of any feeling she expressed was owning up to something now,” reflects Bridget even in the moment. “But it turned out I had no way to answer her or to help.”

If anything, the daughter’s insights only lead to even greater resentment toward her mother. If Hen is somewhat of a textbook narcissist, then Bridget might be as well. The novel ends with Hen growing progressively sicker and eventually dying—without any final moment of catharsis or confession—taking all her painful secrets safely to the grave. Yet for a book titled My Phantoms, death is hardly a resolution for any psychic terror that hasn’t yet been worked through. What Riley’s novels relentlessly enact is simply this: the sheer and terrible potency of these scripts long after they have appeared to run their course.

As suggested by its title, My Phantoms ends much where it begins, which is to say, in the space where most Riley novels inevitably remain. And it is precisely that ongoing buildup—the bewildering, if not entirely surprising, investment in repeating one’s most self-annihilating impulses—that keeps Riley’s readers nervously, desperately turning the page.

Jane Hu is a critic living in Los Angeles.