THE PATIENT was a twenty-six-year-old mother of two, and she had just been sterilized. After getting a diagnosis of Hodgkin’s disease, a lymphatic cancer, during her second pregnancy, the young woman had realized that giving birth again would likely kill her. She had harangued a doctor for months, until he finally agreed to schedule a tubal ligation. When the anesthetic lifted, the first voice she heard was the surgeon’s. “The sterilization procedure was a success,” he said. “And congratulations, you’re eight weeks pregnant.”

The young woman asked her hospital for an abortion; her doctors backed her up. But the hospital board said no. Her life would be endangered by the pregnancy; it wasn’t endangered yet. They kept saying no until finally she convinced two psychiatrists that she would kill herself if she wasn’t given an abortion. Then they said yes.

Similar stories are now playing out in red states across the country, but this scene took place in Chicago in 1968. The young cancer patient, Jody Howard, had never considered abortion in a political context until she needed one and couldn’t get it. Her experience of being denied an abortion—the abjection and terror of it—had seeded a new understanding. No doctor would ever stand in her way again. Eventually, Jody joined Chicago’s underground feminist abortion provider: Jane.

Jane, an illegal, women-run abortion service that operated in Chicago from 1968 to 1973, has become a minor legend in the intervening decades. The group’s story periodically reemerges in the feminist consciousness, gripping younger women’s imaginations. Jane is part cautionary tale, part inspirational narrative. The story of ordinary women, defying the law to take control of their own lives, shows both the desperation and danger of the pre-Roe reality, and the possibilities for solidarity and subversion in a post-Roe landscape.

During its existence, Jane facilitated more than 11,000 safe, illegal abortions. No one ever died from a Jane abortion; thousands were able to live freer, fuller, and more dignified lives. Jane did this all under the noses of both the mob, which wanted to monopolize the abortion market, and the cops, who wanted to eliminate it. Jane members did it without any institutional backing, they did it without any credentials, and they did it without anyone’s permission. They did it for years.

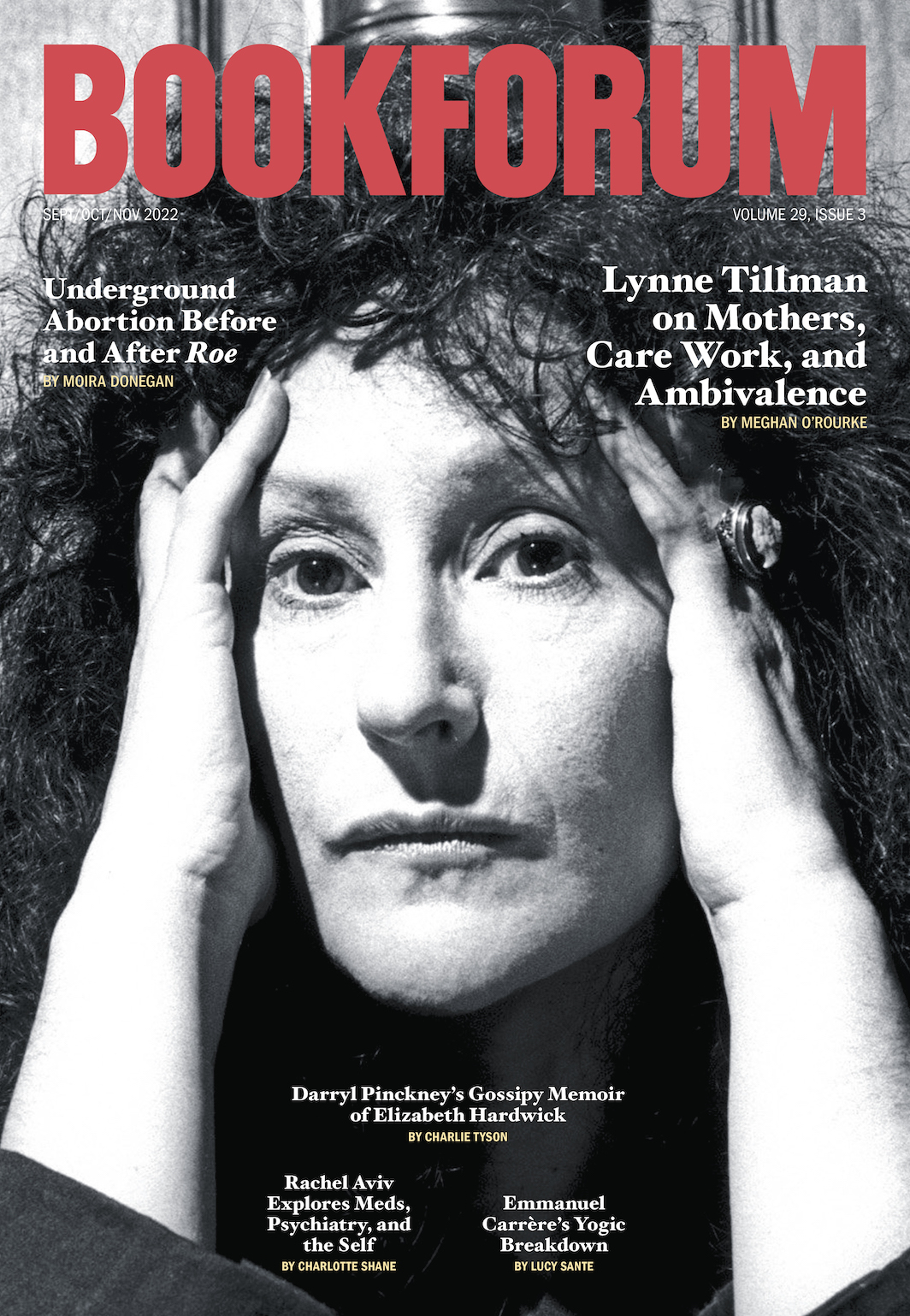

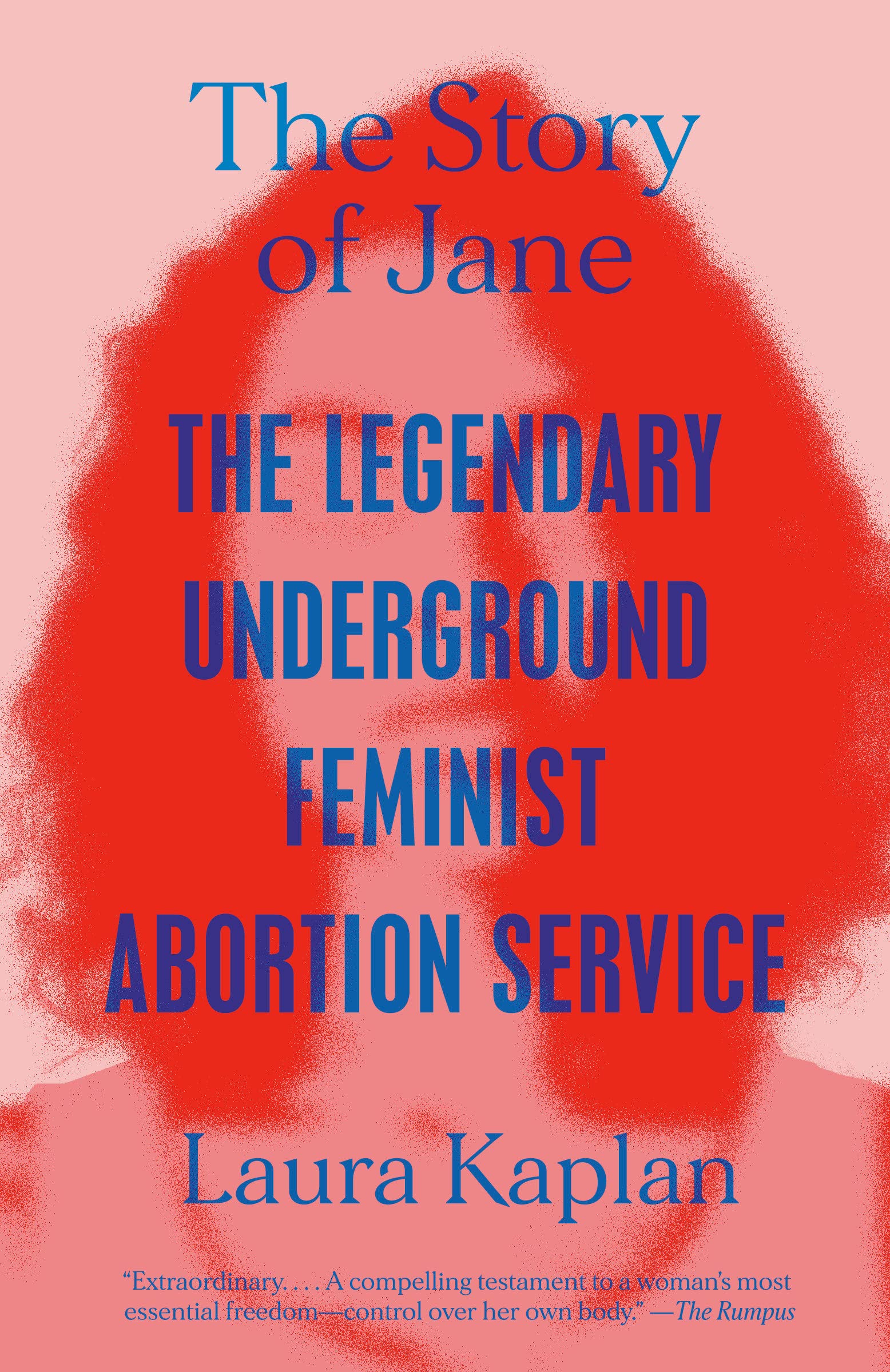

HBO’s new documentary The Janes joins a small canon of Jane histories and tributes. The earlier of these were marked by lingering concerns about harassment and prosecution. The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service, a 1995 history authored by former Jane member Laura Kaplan, referred to each Jane member by a pseudonym. In the 1996 documentary Jane: An Abortion Service, some former Jane members appeared on camera wearing sunglasses to conceal their identities.

The Janes adds little in the way of new information, but it’s valuable in presenting the group to audiences at a time when their message is most urgent. On camera, the women seem newly animated about their past work, as if they’re writing down a dying language. Though there are fewer veterans of Jane still living, there seem to be many more of them willing to talk. Most of the pseudonyms have been dispensed with now, and so have the disguises. Jane members and their associates—husbands, abortion recipients, and the greasy but competent ne’er-do-well, called “Mike,” who was their primary abortion provider for years—appear on camera bearing plain faces, now thin and creased with age.

Jane was unique in its radicalism, its daring, and its yearslong success at evading the law. But in many ways, the service was typical of its time. For one thing, it was hardly the only abortion provider in Chicago. The local mob, known ominously as “The Outfit,” collected protection money from crooked doctors who performed secret abortions all over town. Petty criminals, looking to make a quick buck, often used rudimentary tools to scrape out a uterus. Others sold quinine pills, which were then used to try to induce miscarriages (the pills were ineffective, even in doses high enough to kill you). Quality and safety varied widely, as did the conduct of the abortionists themselves. At the time, Cook County Hospital had an entire ward dedicated to women being treated for botched illegal procedures. Many of those seeking abortions were forced to provide sexual favors to abortionists, in addition to the extortionate prices. Women were blindfolded routinely, both in cars on the way to their abortions and during the procedures themselves. As one Jane veteran puts it in the documentary, if you needed an abortion in Chicago in the ’60s, you could probably get one. “It was more than ‘you were lucky to find someone.’ You were lucky to have it be OK.”

Jane initially began as a tool to navigate this secret and dangerous market. A college student at the University of Chicago had been radicalized after spending time in the South, working with the civil rights movement. When she came back, she began distributing her dorm phone number as an abortion-referral hotline, directing the women who called her to men—and it was always men—who performed illegal abortions. But the student didn’t just point these women in the right direction; she called them back afterward, to ask how it went. Women would report if the abortion had gone well, or if they had needed to go to the emergency room afterward. They would tell her if the provider upped the price at the last minute, or if he demanded a blow job, or if he was drunk. In this way, the student became a clearinghouse for information about abortion providers in Chicago. Women who had had a good abortion would pass the name of their guy on to the student, so she could send other women his way; women who had had bad ones would tell her about it, and their providers would be crossed off her list.

These reliable referrals created more demand, and soon the student could no longer handle the incoming calls on her own. She brought in her friends, young women she’d met in movement politics, who began to take on the work for her. Gradually, the organization, which took on the pleasantly anonymous name Jane, grew and evolved. The group established its own relationships with abortion providers, leveraging the business it could bring in from its referral service to get lower prices. Soon, the group’s organizers had an in-house abortionist, Mike, and they were able to lean on him enough that they could make abortions cheap or free for the women who needed them. They secured their own locations, transported women to the sites, and did their own operational security. They ran their own loan program, coordinated counseling and sex education, and convinced a sympathetic pharmacist to sell them antibiotics, anesthetics, and syringes in bulk.

Eventually, the members of Jane learned to do abortions themselves. They saw the gesture as both operationally and politically necessary. They were always struggling to meet the huge demand, and the problem was compounded by the fact that the group thought abortions should be available to everyone, whether they could pay or not. Doing the procedures themselves gave them the freedom to do as many as they wanted, for free if they wanted. They also believed that women must have total control over their own bodies and lives—not subject to any man’s authority, including a doctor’s. As a Jane member once explained to the leader of another abortion-access group, “This is a male-dominated profession and we don’t think women should have to be so helpless and dependent. We should be able to take care of ourselves.” They got their primary abortionist to teach his craft to Jody, who then helped train the others.

The example of Jane has long been controversial in the reproductive-rights movement, and this is why: in the years when Roe was sturdy but threatened, the reproductive-rights movement used the specter of illegal abortions, and their dangers, as a moral check against the anti-choice movement. Abortion has to be legal, because when it is illegal, women get unsafe illegal abortions, and they die. This was incessantly, brutally true before Roe, and it will become true again.

But Jane’s example stands in contrast to this legend of the dangerous illegal abortion: their abortions were illegal and safe. The fact is that abortions, even dilation and curettage (D&C) abortions like the ones Jane typically performed, are not particularly medically involved. They can’t be safely performed by people who don’t know what they’re doing, but they can be safely performed by trained, calm, and careful non-doctors. Medical advances over the past twenty years, and particularly the introduction of the two-drug medical-abortion protocol, mifepristone and misoprostol, have made illegal abortions dramatically safer. The pills have a lower rate of serious complications than Tylenol; they require no professional training to administer. The medical reality that many illegal abortions are now safe has combined with a political reality: that for many, illegal abortions are now the only abortions available. The reproductive-rights movement has been rapidly playing catch-up in its messaging, moving from depicting illegal abortions as a travesty to showing them as a viable option. Major abortion-rights groups have changed their language around such procedures, from “back-alley” to “self-managed.” When they hold demonstrations, they now discourage protesters from using imagery featuring wire coat hangers.

When Jane was operating, medication abortion didn’t exist yet. The group used the D&C method, mostly, with the occasional later abortion handled via the administration of a miscarriage-inducing paste. In the HBO documentary, a former Jane member empties a bag of her tools onto a table: a speculum, silvery cervical dilators, impossibly long forceps, a curette. It becomes clear that the reason many women died from botched abortions before Roe wasn’t because abortions are particularly hard to perform. It was because so few providers cared enough about women to learn to do them well.

Jane wasn’t like that. Its members made small talk; they made you laugh. There was a conscious effort to make the abortion setting seem as equal and cooperative an environment as possible. Instead of the sterile white sheets of a doctor’s office, the group bought brightly colored linens in florals and paisleys. They wanted no separation of status between the women they served and those who performed the abortions, so if a patient didn’t know what words like “cervix” or “placenta” meant—and many of the women didn’t—Jane would teach her. After the procedure, on their way out, women were given copies of Our Bodies, Ourselves. As Molly, who would later join Jane, told her friend after her own procedure: “I just had an illegal abortion, and it was the best medical experience I’ve ever had.” One of the most common ways that women joined the group was after having their own abortions with Jane.

Which is not to say that there were no divisions between the group members and those they serviced. From the beginning, Jane looked different from their clientele. Like most of the radical-feminist second wave, Jane was largely (if not exclusively) white, mostly college educated, and mostly middle class. Those seeking abortions were more diverse. Though Jane provided abortions to women from all sorts of backgrounds—exhausted mothers and scared teenagers, Polish immigrants and college radicals—as time went on, the group started to meet a huge demand from Chicago’s working-class South and West Sides, and its patients started to look different from its members. They were poorer, that is, and most of them were Black.

For those with only a cursory understanding of the second wave, it’s easy to imagine that groups like Jane were uninterested in race. The truth is that Jane, like many of the radical feminists of their era, were acutely self-conscious and deeply anxious about the whiteness of their group, but also uncertain and uncomfortable with the prospect of changing it. Kaplan describes the questions women asked themselves: “Most Jane members were college educated and middle class. Could they begin to understand the problems of a woman trying to support a family on a minimum-wage income or a meager welfare check?” Many of the Jane women had first come to politics through the Black civil rights movement. But if proximity to Black people’s struggle had been radicalizing, it had not necessarily divested them of personal racism. Across the radical-feminist movement, some white women seemed eager to impress Black women; others seemed irritated or defensive in their presence; still others aimed to place their own political work in the context of the Black movement’s moral authority.

Writing of the radicalization of white women in the ’60s in her 1989 book about the radical-feminist movement, Daring to Be Bad, the historian Alice Echols notes that white women seeing Black women in movement politics helped prompt their original reconsideration of gender. “White female activists began to question culturally received notions of femininity as they met powerful, young black women in SNCC and older women in the black community who were every bit as effective as male organizers and community leaders,” she wrote. But on the other hand, this very difference also made Black women feel skeptical of women’s liberation, or struggle to see its relevance to their own lives. “Black women’s tendency to dismiss women’s liberation as ‘white women’s business’ was related to the fact that middle-class, white women were struggling for those things—independence and self-sufficiency—which racial and class oppression had thrust upon black women.” Gender oppression looked different for women across racial lines; this difference proved perilous and difficult to organize across.

It is also worth being honest about something: the women in Jane, like a lot of white people today, were almost paralyzingly afraid of being called racists. At the time, the Black Power movement—a more radical outcropping of the liberal reformist civil rights movement where many of the Jane members first cut their political teeth—was going through an evolution with regard to gender politics, becoming less conservative and more egalitarian. But many of the white Jane members still perceived groups like the Black Panthers, who were prominent in Chicago at the time, as hostile to women’s liberation, skeptical of birth control, and placing great emphasis on family and babies. They weren’t sure how their own work would be received by that movement. The Janes were also acutely aware of how their abortion service could look in the context of the widespread forced sterilization of Black women and girls by state institutions and Southern white doctors. “As white women performing abortions for poor black women, they were vulnerable to accusations of genocide and racism,” Kaplan says. These worries raise the question: Who were the Janes trying to protect?

The problem accelerated after abortion became legal in New York in 1970, a development that all but eliminated the white, middle-class women who could afford to travel from Jane’s clientele. As the gap between providers and patients deepened, so did the anxiety within Jane. “Every few months at meetings they discussed the need to broaden their membership,” Kaplan says. “But the composition of the group remained basically the same.” “I wonder about how offensive we may have unintentionally been,” one former group member says in The Janes, reflecting on the perils of this gulf. The membership of Jane wasn’t changing as quickly as the demographics of their patients were. They tried to recruit from the South Side and West Side women they were giving abortions to, but as they say in the documentary, “We didn’t get a lot of takers.”

Why not? Black women didn’t want to join an overwhelmingly white group, for one thing. But another reason may have been the nature of the work itself: illegal, and therefore especially risky. In Kaplan’s book, Jane’s only Black member, given the pseudonym Lois, recounts her decision to join the group. She had accompanied her Black friend to a Jane abortion and had been struck by the group’s racial asymmetry: white women performing the abortions, Black women receiving them. She decided to join in part because she thought it would help the patients to see more people like her. “You guys are the white angels that are going to save everybody and where are the black women at?” she asked a Jane member. “Maybe I can identify with black women a little better.” But her friend tried to talk her out of it: “You’ve got three children. My God, what would happen if you got arrested? Those white women would get out of it, but not you. Girl, you could go to jail. They’d take your kids away.” On the one hand, Jane’s whiteness was clearly a failure of organizing—a failure to recruit more women of color, and a failure to make membership more appealing to them. On the other hand, it can also look like an appropriate distribution of the risk. The white women who took on the most criminal liability were the ones least likely to be screwed by the criminal legal system.

The Jane members didn’t only look different from their clientele because most of them were white. They also looked different because they were so very young. The group had been started by a college student, who recruited from the youth-dominated civil rights, women’s liberation, and student movements. Its work was dangerous and demanding. Jane appealed to women with little to lose, or without a full grasp of what it meant to gamble with their own freedom, and these women tended to be in their twenties. As time went on, new recruits skewed even younger. One woman, given the code name Nora in Kaplan’s book, volunteered to live full-time in an apartment that Jane had rented, and to act as a midwife for second-trimester induced miscarriages. Nora spent a year there, talking to women who came in, making sure they didn’t have complications as they labored and delivered, helping them keep secrets from their parents, their churches, their husbands. She was nineteen.

The group had only two rules: never lie to a woman, and treat everyone who comes through the service the way you would want to be treated. But in practice, the group did lie, both to those it served and to itself. First, they lied when they referred to Mike, the man who performed most of their abortions in the early years, as “the doctor.” Mike wasn’t a doctor; he was a small-time crook, who had learned the abortion trade on the edges of the underground economy. Mike was cocksure and uneducated, slightly vulgar in a good-natured way. The Janes shows yellowing photographs of him from the 1970s; he has a toothy, guileless grin, and the deep tan and messy hair of a beach bum. He said that he thought abortions were like mink coats: something lots of women wanted, but only a few of them could afford. In the HBO documentary, one of the former members said he seemed like a con man. Another said that he had once given her pointers on how to break open a safe. But Mike was an exceptionally good abortionist. He had excellent technical skills and a good bedside manner; his jocular ease helped women relax. You can see why the women kept him around. He was a bad liar, and he wasn’t too bright, so he was easy for them to control. In other words, he was trustworthy.

Maybe the fiction that Mike was a doctor was something that the members told themselves to ease the risk they were taking in Jane. But on the other hand, maybe it was easy to pretend that Mike was a doctor because almost none of the members ever met him. For a long time, the reality of who was performing the abortions—and how, and where—was a tightly guarded secret among an inner circle of the group. Because the other lie that the group told themselves was that Jane had no leader. Officially, Jane was nonhierarchical, opposed to authority, a group of equals. Unofficially, everyone knew that Jody Howard was in charge.

Jody, the young mother with cancer, was not the only person in Jane making decisions about the group’s operations. She was not the only person shaping its political stance. But even if Jody didn’t make every major choice in Jane, every major choice seems to have been made with Jody’s consent. In interviews, Jane members speak of Jody as singularly charismatic and intense, the sort of person you find yourself trying to impress without quite knowing why. At meetings, she let her right-hand man and confidante, Ruth Surgal, do most of the talking; Jody, overwhelmed with anxiety and passion for the project, would stand silently in the doorway, compulsively chewing the erasers off pencils.

It was Jody who first found Mike, and Jody who put him up at her house when he came to Chicago from out of town to perform abortions. It was Jody who was the first to attend the abortions, and then Jody who was the first to perform them after Mike. It was Jody who another Jane member called late one night, in a panic, after she got a threatening phone call from the irate husband of a Jane patient, screaming that he was coming for them. Jody told her to ignore it; the asshole was probably bluffing. They never heard from him again.

In pictures from the era, Jody has a guileless beauty. She’s boyishly thin, with short black hair and huge, wide-set eyes. But Jody could be secretive and lightly duplicitous; she guarded information more diligently than was necessary, and she pursued her vision for Jane with little regard for other people’s preferences. Jody resented the heavy burden of leading the group, and its members resented her unwillingness to share that burden. Feelings got hurt. And dealing with Jody was delicate: in addition to her personal magnetism, she had a moral authority within the group that made her difficult to challenge. She knew more than anyone, and she did more than anyone. And she had cancer.

In interviews now, Jane members speak with caution about the internal dynamics of the group. They are protective of Jane, but it is clear that the experience of being in it was wounding for many of them, a combination of fiercely held principles, shifting loyalties, and exceptionally high stakes that left many of them exhausted and scarred. Throughout its tenure, Jane had a high turnover rate; there was often abundant interest in joining, but the work was so demanding that most women didn’t last long. Oddly, I find Jane’s internal toxicity and strife to be among the most inspiring aspects of the group. Against impossible odds, the group accomplished something heroic and generous, stood by their principles in the face of great consequences, helped women become safer and freer. It is the kind of story that could easily slip into myth, its characters lionized as impossibly strong, semi-divine. The Janes, appearing on camera still clinging to their gripes and grievances, don’t allow us this fantasy. Their flaws are a challenge: If mere human beings can do something like this, what can you do?

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe in June, there has been an outpouring of moral ambition around abortion rights. Women took to social media to offer up their homes to out-of-state travelers; others openly declared that they would help women break the law. For a while on Twitter and TikTok, the term “camping” was trending, a winking euphemism for illegal abortions. But the reproductive-rights movement now is not what it was in 1969. Wearied by decades of legal and political assaults from a much more powerful far right, many abortion-activist groups received this outpouring with exhaustion and even contempt. They mostly rolled their eyes; a few of them issued scolding missives telling people to knock it off. It’s hard not to sympathize with their frustration: the outpouring online often looked more like an expression of moral vanity than a commitment to long-term action. Some posts betrayed a misunderstanding of both the medical aspects of abortion and of the law. But these “camping” posts represent women sympathetic to the cause, expressing a willingness to help. They should be educated and organized, not condescended to and discouraged.

The example of Jane shows that a sense of moral outrage, combined with the opportunity to act, is sufficient to make ordinary people into radical political actors. The women in Jane came from many different ideological backgrounds across the left: they were milquetoast liberal reformers and bomb-throwing radicals, workers and intellectuals, Democrats and communists. They didn’t waste time perfecting everyone’s political analysis in order to make them pure enough to do the work. They did the work, and that experience changed their political analysis.

Eventually, the pressure of cancer, motherhood, Jane, and her job became too much for Jody. She announced that she would be taking a step back from the service and checked herself into a psych ward. Maybe it was because Jody wasn’t around that Jane finally got caught. In May of 1972, two women presented themselves at a Chicago police precinct: they told the cops that their sister-in-law was going to have an abortion, and that they wanted the police to stop it. Cops raided the apartment where Jane was performing abortions. Seven members were arrested. Charged with multiple counts of abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion, they each faced 110 years in prison. How did they get off? Roe v. Wade was decided in January of 1973, rendering the laws they were accused of breaking unconstitutional. The DA dropped all the charges. With abortion now legal, Jane saw no reason to continue their services. They threw themselves a party to celebrate what they’d done, calling it the “Curette Caper.” Then they closed up shop and resumed their separate lives.

It’s this Cincinnatus quality that astounds me about the members of Jane: the way they simply stopped the radical and visionary thing they had done when it was no longer necessary, and the way they resumed lives of anonymous usefulness somewhere else. In a country that took women seriously as moral actors, or a country that viewed the struggle against sexism as a struggle for the freedom of the human spirit, there would be statues of the Jane women in every town square. In this world, they became teachers, health-care workers, civil bureaucrats. Jody died in 2010 on a farm in Tennessee, from complications of the same Hodgkin’s disease she had been diagnosed with in her early twenties. Jane had disbanded, in part, because it thought it had ushered in a better world. For a little while, it did.

Moira Donegan is a writer and feminist in New York City.