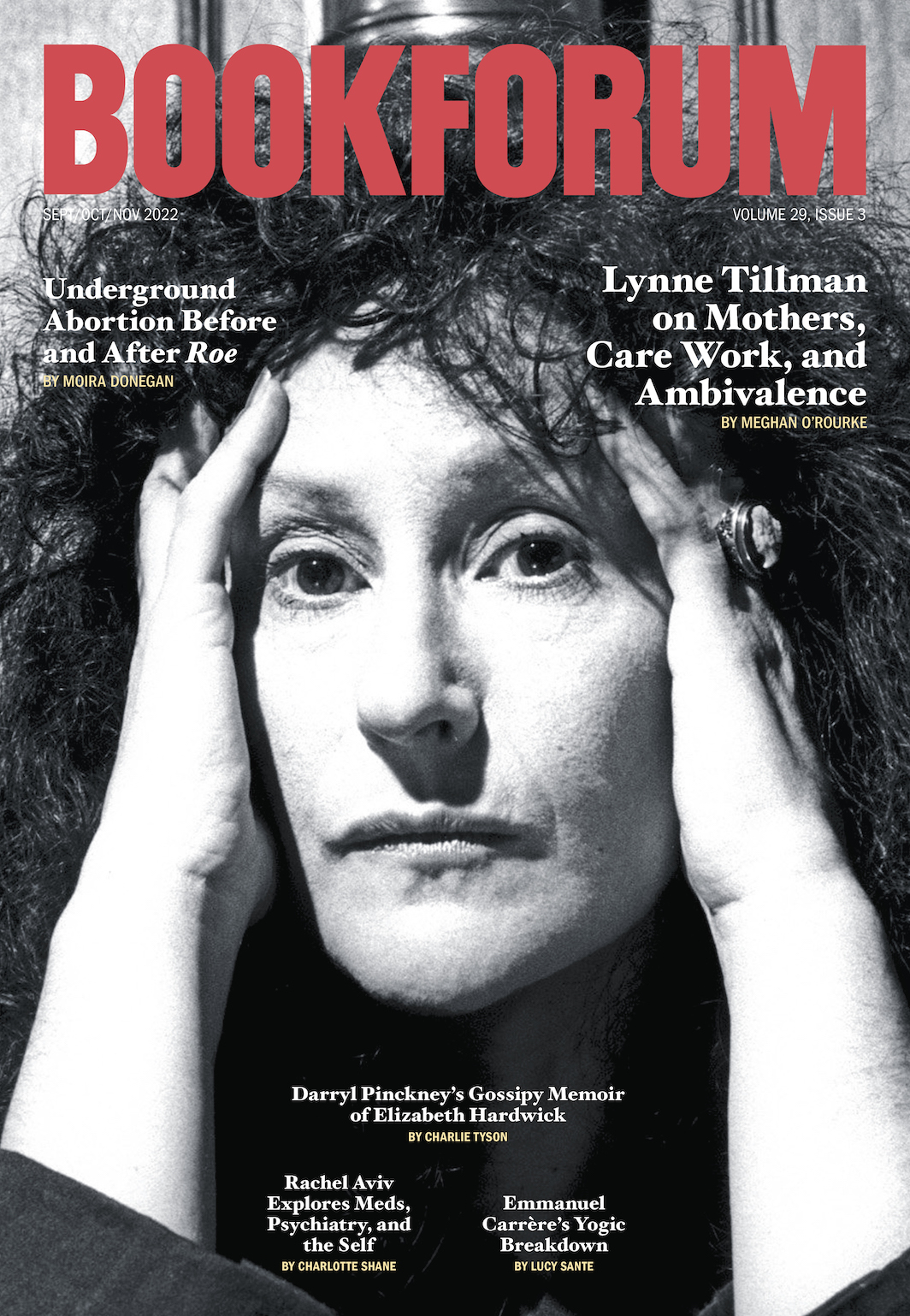

![Sonia Delaunay, Robes simultanées (Trois femmes, formes, couleurs) (Simultaneous Dresses [Three Women, Shapes, Colors]), 1925, oil on canvas, 57 1/2 x 44 7/8". © PRACUSA S.A./Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid](http://images.bookforum.com/uploads/upload.000/id25075/article00_1064x.jpg)

IN 1913, Sonia Delaunay appeared in a Parisian ballroom wearing a dress she had designed. A Cubist patchwork of vivid colors, the garment inspired enthusiastic reactions from artists and poets already immersed in the European avant-garde. Blaise Cendrars wrote a poem to the dress; Apollinaire encouraged his readers to visit the dance hall on Thursdays when Sonia and her husband Robert Delaunay arrived arrayed in the clothes she made. The Robe simultané (Simultaneous dress) was Sonia’s attempt to activate via bodily motion the color dynamism she was exploring in her abstract paintings. A rhythm of interacting hues might be achieved by, as she described it, “blending light and motion and scrambling the planes.” Providing a substantial overview of her paintings, this volume also pays particular attention to Delaunay’s often-neglected but lifelong focus on fashion and fabric design. While the Odessa-born artist, who died in 1979, figured prominently among early modernist painters, she turned readily to what could be called commercial work. In 1918, she started a company that sold ceramics, pillows, and clothes that featured her bold deployment of color in stark, deliberately flat geometric patterns. If this technique anticipated Color-Field painting by decades, her propensity for multifarious mediums and collaboration appears from a contemporary vantage as even more advanced. One of her most famous creations, the artist’s book Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Little Jehanne of France, was done with Cendrars. She produced costumes for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, created a series of “poem dresses” with Tristan Tzara, and even decorated a sports car. She blurred the artificial line between fine art, fashion, and commerce in ways now made familiar by, say, Richard Prince, and Virgil Abloh.

Delaunay’s studies for dress and costumes demonstrate a complex interplay between color theory and fancy. These are not close-fitting frocks meant to grace the wearer’s body; rather, that body is expected to flatter the dress. The colors, shapes, and Orphic patterns combine for an animated effect that is enhanced by their active presence in the world. She insisted that the finished fabrics not be rendered too perfectly—that they retain the spontaneous quality of her sketches. A photograph of Romanian dancer Lizica Codreanu, on the set of René Le Somptier’s 1926 film The Small Parisian One, garbed in Delaunay’s Pierrot-Éclair costume, conveys some sense of this sought-after kineticism. Electric bolt-like lines shoot down to the dancer’s toes and are mirrored by her overall posture, in particular her bent leg and angled arms. The concentric rings rendered in different colors (circles are ubiquitous in the paintings) seem to rotate around the head. Even in this still image, Codreanu emerges from the jagged backdrop with propulsive energy. Delaunay always sought to evoke movement as it exists in tension with the fixity of objects. By ignoring the conventions and hierarchies of the art world, she showcased that dynamism well outside its bounds.