“BEAUTY, WOMEN’S BUSINESS IN THIS SOCIETY, is the theater of their enslavement,” laments Susan Sontag in her 1972 meditation on aging and femininity. “Only one standard of female beauty is sanctioned: the girl.” It is no accident that women must look like girls to qualify as beauties, for they must also act like girls to qualify as women. “The ideal state proposed for women is docility, which means not being fully grown up,” Sontag continues. Only two ages are available to women: infantile—and too old.

No one understood the injustice of the girlish imperative better than the French writer and provocateur Colette, who made her debut in the guise of an adolescent narrator. Claudine is fifteen when we meet her in Claudine at School (1900), the opening installment of Colette’s first series. Mischievous, quick-witted, and sexually precocious, Claudine is a charming constellation of contradictions, at once a girl and a living rebuke to the myth of innocent girlishness. Her father leaves her largely to her own devices, and her days are devoted to rambling around the woods, teasing her teachers, and bullying her schoolmates, who are

so young lady-ish that they annoy me. They’re frightened of being scratched by brambles; they’re frightened of little creatures such as hairy caterpillars and those pretty heath spiders that are as pink and round as pearls; they squeal, they get tired—in fact, they’re insufferable.

Claudine is such a defiantly feral specimen that it is difficult to say whether she reinvents girlishness—or whether she rejects it altogether. In the second of the Claudine novels, Claudine in Paris (1901), Claudine’s elegant gay friend Marcel strikes onlookers as “much more of a girl than she is,” and when she marries the inevitably middle-aged Renaud in the third book in the series, she discovers “how much more feminine he is than I am!” Even in marriage, the state that befits a demure young woman, proper girlishness evades the incorrigible Claudine.

Colette’s heavily autobiographical first novels are a fitting introduction to her work, both by dint of their preoccupations and by dint of the circumstances of their publication. They were written at the urging of Henri Gauthier-Villars, Colette’s first husband and a pillar of the Parisian demimonde who was fourteen years her senior. A music critic second and a carouser first, Gauthier-Villars appended the pseudonym “Willy” to the novels that he made little secret of outsourcing to a veritable army of ghostwriters. The Claudine novels first appeared under this name, and it was Gauthier-Villars who collected the considerable profits when they became best-sellers.

Later, Colette would become infamous for her string of lesbian affairs, her stint in the theater (especially her performances in drag), and her brief affair with her second husband’s sixteen-year-old son. But she was twenty—and achingly inexperienced—when she left the Burgundian countryside to accompany Willy to Paris. She had yet to develop her characteristically cheerful disdain for convention, and it was largely in print that she was able to mount resistance to the exploitative terms of her marriage. No wonder that the Claudine novels, the first of which was completed when Colette was only twenty-four, already evince their author’s fascination with the jejunity that defines femininity, the young girls who struggle to achieve it, the older women who struggle to retain it, and the men who are eager to profit from it. For the rest of Colette’s life, the figure of the girl would dominate her work: her two most commercially successful works, the Claudine novels and the 1944 novella Gigi, both follow teenagers involved with older men. But even when Colette seems to take up the opposite theme—that of old age—she is in fact approaching the question of girl from the inverse angle. Can girls survive their maturation? Can women juggle the conflicting imperatives to muster girlish docility and maternal authority? And what happens when they cannot? In perhaps Colette’s most haunting story, “The Kepi,” an older woman is thrust into a second adolescence by a mad passion for a younger lieutenant. Despite the woman’s efforts to appear youthful, she makes the fatal mistake of trying on her lover’s kepi after a tryst. All at once, he sees

the slack breasts and the slipped shoulder straps of the crumpled chemise. And the leathery, furrowed neck, the red patches on the skin below the ears, the chin left to its own devices and long past hope. . . . And that groove, like a dried-up river, that hollows the lower eyelid after making love, and that vinous, fiery flush that does not cool off quickly enough when it burns on an aging face. And crowning all that, the kepi! The kepi—with its stiff lining and its jaunty peak, slanted over one roguishly winked eye.

The woman’s male friends discuss her predicament unsympathetically. One remarks that her “most urgent duty was to remain slender, charming, elusive.” The other replies, “she fondly supposed that being the forty-six-year-old mistress of a young man of twenty-five was a delightful adventure.” “Whereas it’s a profession,” the first man affirms.

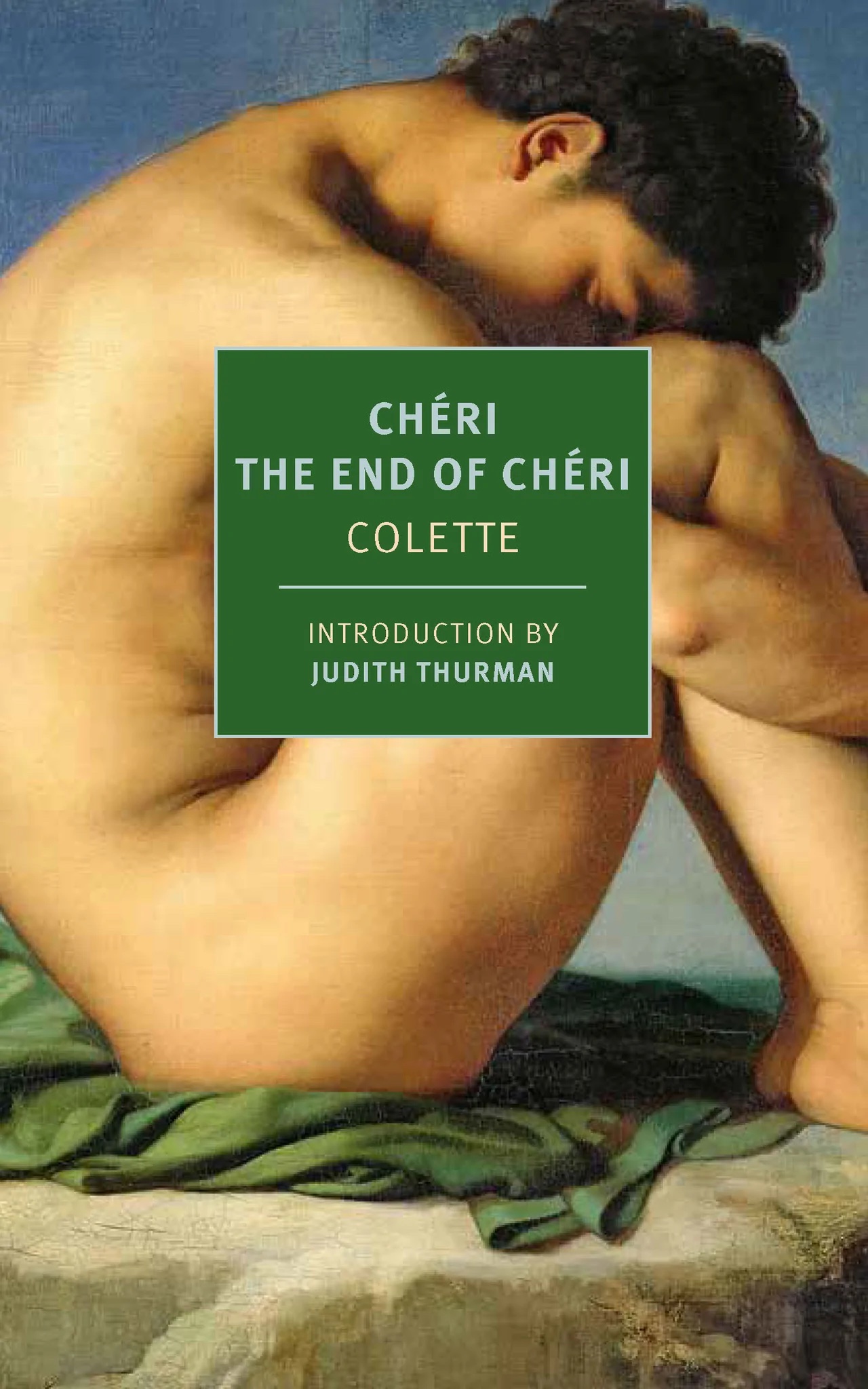

But Colette’s most marvelous and mature reckonings with age and youth, the newly and gracefully translated Chéri (1920) and The End of Chéri (1926), demonstrate the derangement of infancy extended beyond its natural limits. A woman who refuses to submit to the standard set by the girl grows old with poise, while a perpetually puerile young man remains pitiful forever. Male or female, Colette concludes, an eternal child is doomed to grow grotesque.

AT THE BEGINNING OF CHÉRI, the elegant Léa de Lonval is forty-nine and “approaching the end of a successful career as a well-heeled courtesan.” She is still unapologetically voluptuous, a devotee of “order, beautiful linens, aged wines, refined cuisine” with a rare talent for aestheticizing even daily drudgeries. For lunch, she lingers over “dry Vouvray and the June strawberries served, with their stems, on a faience dish the color of a wet green frog.” Her house is opulently appointed, lit with roseate lamps.

Her lover, the titular Chéri, is twenty-four, “with a white marble face that look[s] invincible.” Despite his formidable beauty, he craves a mistress who can double as a surrogate mother—and Léa, who only half-jokingly calls the affair “an adoption,” is eager to oblige. Corralled into the unenviable role of young-girl-cum-old-mother, she dusts powder over her wrinkles and applies henna to the graying roots of her hair—even as she babies her young protégé, catering to his every whim. During their affair, she addresses him exclusively by his childhood pet name, never by the unbearably pedestrian “Fred,” and in her internal monologues he goes by the moniker of the “bratty nursling.” For his part, Chéri calls his caretaker “Nounoune,” the endearment he devised for her in his infancy, since which time she has maintained an “irascible friendship” with his mother. Chéri’s adoption has lasted six years, but when his eponymous novel opens, he is at last on the verge of making a suitable marriage to a wealthy girl his own age.

Léa does not think she is in love with Chéri, and she is surprised to find herself heartbroken when her bratty nursling departs on his honeymoon. She feels so horrible that she takes her temperature to determine whether she is ill. The results are revealing: “So, it’s not physical,” she observes sensibly. “It’s that I’m suffering. Something’s going to have to be done about this.” Much is done in due course, all of it in Léa’s characteristically unsentimental style. A trip is planned; elaborate meals are eaten; appearances are maintained. When Léa returns to Paris months later, she prepares for a visit to Chéri’s mother, telling herself,

two women, a little bit older than last year; their usual malice and idle chitchat, their mild suspicions, the meals they share; reading the financial papers in the morning, exchanging spicy gossip in the afternoon: all of this has to start over again, because it’s life, because it’s my life.

It is her life—and she is heroically up to the challenge of it, even in the aftermath of what she knows to be her last great love.

But the pampered Chéri does not have Léa’s flair for living bravely in the face of difficulties. He misses not just his lover but the idyll she so artfully conjured—the pastries she ordered for him in the mornings, the lavish comforts of her well-furnished house. When he returns from his honeymoon, he plays truant, holing up in a hotel and avoiding his wife and mother. At last he can hold out no longer, and he materializes in his old mistress’s bedroom in the middle of the night.

Unlike the protagonist of “The Kepi,” Léa understands that being the mistress of a man of twenty-five is a profession, even a discipline. Chéri has never “surprised her unkempt, or with her bodice unlaced, or wearing slippers during the day.” But when he appears after such a prolonged absence, she emits “a short burst of stifled laughter” and realizes with horror that she is “close to abandoning herself to the most terrible joy of her life.” It is too late to avert the catastrophe: “her caution, born of experience; the cheerful common sense, which had guided her life; the doubts and humiliations of her advancing years; along with her acts of renunciation; all of these shrank and vanished before the presumptuous violence of love.” Like so many of Colette’s male characters, Chéri cannot forgive the woman he supposedly adores for her outburst of unseemly humanity. When he glimpses Léa’s face “with no make-up on yet, a meager braid of hair on her nape,” he is repulsed. Devastated but realistic, Léa recognizes the change in her adoptee’s mien, instantly grasps what it betokens, and sends him off to grow up.

In The Last of Chéri, several years have passed, but Chéri has yet to mature. The bratty nursling has witnessed the horrors of the front without graduating to “Fred.” His admirably efficient wife, from whom he is politely estranged, runs a military hospital; his mother makes savvy financial investments and plans dinner parties. While these capable females bustle around him, Chéri disintegrates. Whenever he catches sight of his face in the mirror, he experiences a “mild shock”: he cannot “comprehend that this was no longer the exact image of a twenty-four-year-old,” nor can he accept that Léa is nearly sixty. When at last he pays a visit to her in her new apartment he thinks, “Who can that old woman be?”

His former lover has grown unrecognizably “vast, invested with a generous development of every part of her body.” Her arms are “as fat as thighs,” and her careless attire bespeaks “the usual abdication and withdrawal from femininity.” But much to Chéri’s outrage, this monstrous perversion of his romanticized memories appears to be at peace with her condition. She carries on calmly, recommending a hearty neighborhood restaurant and musing, “I’m glad to remember what we had. I’m quite happy with my past. I’m quite happy with my present.” Chéri recoils in horror. “She’s trying to make me believe it’s easy, even enjoyable, to turn into an old woman,” he thinks.

Let her tell that to other people! Let her tell them her fibs about what a good life she has, about the bistro with its country cooking. But not me! I was born surrounded by fifty-year-old beauties, electric massagers, and smoothing creams! Not me, who’s seen all of my painted pixies fighting over the suggestion of a wrinkle.

But even when Chéri rudely asks his former lover and adoptive mother if she intends to get dressed to go out, Léa refuses embarrassment. “And in what, milord, would you like me to get dressed?” she laughs. “I am dressed. . . . Dressed for living, I’m telling you! In things that are easy, comfortable.” But while a beaming Léa gorges herself on country cooking, Chéri is wasting away, eating so little that he becomes “almost incorporeal.” There is not much left for him to destroy when he kills himself.

Before Chéri came his prototype, Clouk, a character who appeared in a number of loosely linked stories. “When I gave birth to this beautiful young man,” Colette reports, “he was ugly, something of a runt, and sickly.” Later, he “cast off his pale little slough like a molting snake, emerged gleaming, devilish, unrecognizable.” But in fact Chéri bears more of a resemblance to his frail predecessor than Colette cares to admit. Even the bratty nursling’s beauty cannot save him from his triviality. One night his wife watches him sleep and thinks, “How insignificant he is.”

COLETTE’S ULTIMATE ANSWER to the question of girls and their expiration is that they cannnot last: either they fall from grace despite their best efforts, as in “The Kepi,” or they deliberately embrace old age with a haughty and honest dignity, as in The End of Chéri. Indeed, Colette favors women who cast off the mantle of girlhood much earlier, sometimes even as early as adolescence. At fifteen, Claudine is already too independent to count as much of a girl—and, truth be told, the bratty nursling has no right to be so scandalized by Léa’s transformation, for her end state is no more than the logical extension of her initial trajectory. “Marriage between an old woman and a young man subverts the very ground rule of relations between the two sexes,” writes Sontag. “Women are supposed to be the associates and companions of men, not their full equals—and never their superiors.” Léa was always too competent and too redoubtable to resign herself to the coquettishness that Chéri expected of her, even as he also demanded that she serve as his obliging parent. In The End of Chéri, she has at last advanced beyond the constraints of gender to achieve the “sexless dignity” at which her conduct had always gestured.

But the feint of girlishness is not without its benefits, for the project and production of womanhood provides a rigorous education. To be the mistress of a younger man—to be a girl at all, but especially to be a girl forever—is indeed a profession. For once, Chéri recognizes the truth of the matter when he coldly appraises his young wife and reflects, unimpressed, that her natural beauty is “not fair.” The invocation that hovers in the air, implicit yet palpable, is of Léa, whose beauty is earned by her labors at the dressmaker’s and the makeup table. Colette is often described as an apolitical writer, and at least one critic has pronounced her a specialist in “amoral” female characters, but many of her most memorable protagonists embody a quiet and unostentatious morality: their virtues consist in their ruthless social intelligence and their quiet but heroic capacity for getting on with things. Léa is beautiful because she has the acumen and the courage to make herself so, even when every social force conspires to convince her that she is beyond beauty, beyond relevance.

But if girlishness takes work—and refusing to be a girl takes not just work but daring—what does manliness take? Colette’s biographer, Judith Thurman, notes that the men in her subject’s fiction “tend to be shallow, yet however terribly they behave, she pities them as the weaker sex.” They are flabby, self-indulgent, and utterly without resilience. They never have to master the difficult art of self-curation, and as a result, they are stunted. The girl grows up while the man stays boyish forever. Claudine ripens into Léa, but Chéri simply rots.

Becca Rothfeld is a contributing editor at The Point and the Boston Review. Her debut essay collection, All Things Are Too Small, is forthcoming from Metropolitan in the US and Virago in the UK.