“IT MAY BE THAT THE subconscious is really a committee,” Cormac McCarthy tells Oprah in their 2007 interview, a full eight years before he could have gotten the idea from Disney-Pixar’s Inside Out. “They may have meetings and say, ‘What do you think we should tell him? Should we tell him that? Nah, he’s not ready for that.’ . . . Sometimes the sense of the subconscious and its role in your life is just something you can’t ignore. It may have to do with the subconscious being older than language, and maybe it’s more comfortable creating little dramas than telling you things, but it has to understand language.”

“I love that thought,” Oprah replies, fingering a lock of her hair. “The subconscious being older than language—I hadn’t thought of it that way before.”

A decade later, McCarthy would revisit this subject in an essay published in Nautilus magazine. “The Kekulé Problem” takes its title from an anecdote (which he’d also shared with Oprah) about the nineteenth-century German chemist August Kekulé, who was trying to find the structure of benzene. After much fruitless labor he went to sleep and dreamed of an ouroboros. He woke up knowing that the structure of benzene must be a ring. “Why the snake?” McCarthy asks in the essay. “That is, why is the unconscious so loathe to speak to us? Why the images, metaphors, pictures? Why the dreams, for that matter.”

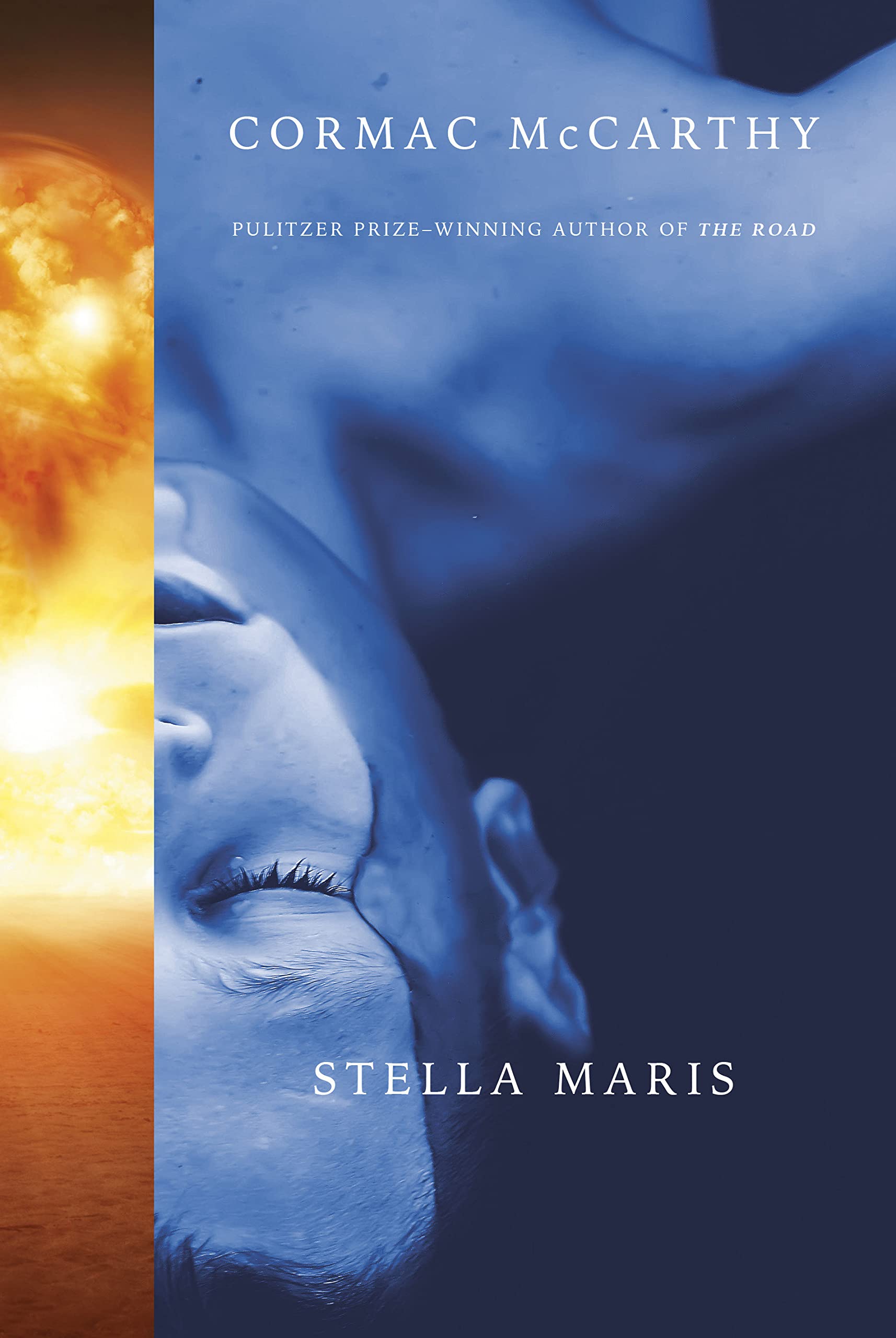

These questions are posed again—and again and again—in a lopsided pair of new novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, McCarthy’s first works of fiction since winning the Pulitzer Prize for The Road in 2007. As it happens, I have a long-held question of my own to pose, one which has been on my mind in a general way for most of my serious reading life, and has become acutely troubling ever since Knopf announced these novels back in March: Is Cormac McCarthy our most minor major novelist or is he our most major minor novelist? The new books, unequal though they are in terms of quality, are his most ambitious and challenging work in decades. They do not readily yield a definitive answer to my question, but they do suggest that it may be as much on his mind as it has been on mine.

CORMAC McCARTHY’S FIRST NOVEL, The Orchard Keeper, was published in 1965, three years after the death of William Faulkner. That book, set in rural Tennessee, is deeply Faulknerian in its attention to the lyrical potential of Southern speech, as well as in its sumptuous descriptions of Appalachian landscapes and people. McCarthy’s editor was Albert Erskine, who had been Faulkner’s editor, and so the stage was set for a certain Southern gothic torch to be, well, if not passed exactly, then reignited. But the novel flopped. So did McCarthy’s next several: Outer Dark (1968), Child of God (1973), Suttree (1979), and even Blood Meridian (1985) all flopped. The early work flopped so hard, and the later work hit so big, that a critical study of the shift—Cormac McCarthy’s Literary Evolution: Editors, Agents, and the Crafting of a Prolific American Author by Daniel Robert King—was published by the University of Tennessee Press in 2016.

With Blood Meridian, McCarthy had traded the woods and caves and backroads of the Southeast for the plains and deserts and big skies of the Southwest. After Blood Meridian he simplified the language and softened the violence in his books; his subsequent novels still boast sizable body counts, but there’s less glee in the killing, and corpses are radically less likely than heretofore to get scalped and/or fucked. The other big change was editorial: Albert Erskine retired from Random House in 1987, after twenty-two years of failing to deliver for McCarthy (or McCarthy for him) the kind of commercial and critical success that had come to Faulkner, Ralph Ellison, and Eudora Welty. McCarthy was handed off to Gary Fisketjon, then a hotshot young editor who had already made a name for himself by creating the Vintage Contemporaries series and was becoming one of the imprint’s most reliable hitmakers.

McCarthy, an infamous recluse, did not do press or give readings or teach. He had never had a book sell more than five thousand copies. He didn’t always have a fixed address. Random House was ready to cut bait. But McCarthy’s next book wasn’t another Joycean carnival like Suttree or an orgy of violence like Blood Meridian. All the Pretty Horses (1992) is a bona fide page-turner, a midcentury Western about a truehearted Texas boy named John Grady Cole, who, when his dissolute mother decides to sell the family ranch, sets out for Mexico with his trusty horse and equally trusty best friend to seek their fortune as honest cowboys, only to find romance and danger at every turn. It is a very good novel, intermittently a great one, and Fisketjon must have known right away that he had a hit on his hands. McCarthy, who by 1992 was living in New Mexico, gave his first major interview to Robert Woodward of the New York Times on the occasion of All the Pretty Horses’s publication. Woodward called him “the best unknown novelist in America.” McCarthy was fifty-eight years old, and that was the last time anyone would ever say that about him.

All the Pretty Horses was a best-seller. It won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award. McCarthy wrote two sequels—The Crossing (1994) and Cities of the Plain (1998)—which together comprise his Border Trilogy. Next, McCarthy wrote an original screenplay, a border noir called No Country for Old Men. He could not find a producer, so he cut his losses by revising his script into a spindly little novel that Knopf put out in 2005.

The Road was published in 2006. This comically bleak and self-serious apocalypse fable tracks an unnamed father and son as they cross the blighted United States on foot, dodging bands of cannibals and mumbling to each other that “we are the good guys” and so it is up to them to “carry the fire” of civilization. There are a few memorable episodes—the underground bunker, the half-sunk ship—and one excellent paragraph about trout, but it’s a silly, forgettable piece of YA that desperately wants you to believe it is the Book of Job. Which wouldn’t have been a problem if so many adults hadn’t taken it as seriously as it took itself. The Road was a smash best-seller and an Oprah’s Book Club pick, and it won the 2007 Pulitzer despite having been published the same year as The Emperor’s Children, Everyman, Eat the Document, All Aunt Hagar’s Children, and The Collected Stories of Amy Hempel. 2007 was also the year that the Coen brothers released the film version of No Country for Old Men, adapted from the novel but using their own screenplay rather than McCarthy’s. The film grossed $171 million dollars at the box office, won four Academy Awards, and immortalized Javier Bardem as the dead-eyed assassin Anton Chigurh.

McCarthy was seventy-three when The Road was published. Every year that went by without a follow-up, the prospect of getting one seemed to dim. That was fine by me because my sense was that the quality of his books had been inversely proportional to their notoriety for at least twenty-five years. My favorite McCarthy novels are those of the ’70s and ’80s. Outer Dark and Child of God are lean gothic wonders that owe more to Poe than to Faulkner; they’re foul brilliant Manichean night terrors whose ethical and spiritual convictions are expressed entirely through inference by omission. Suttree is a high-modernist medicine show that could only have been written by a writer who lived through postmodernism and thought most of it was bullshit. This raucous, hallucinatory novel of riverine and subaltern Knoxville is a hundred pages too long, and some of its episodes are expendable (miss me with that fever ward), but it’s the most exciting book McCarthy ever wrote. I find that its heights and depths of positive and negative sublimity hit harder and linger longer than those of Blood Meridian, an admittedly more legible and even more “important” novel, but one whose single-mindedness of theme and execution checks Poe’s box for “unity of affect” without ever quite fulfilling my deepest readerly desire: to witness true genius encountering itself in a moment of self-surprise. Blood Meridian is consciously indebted to Moby-Dick, and Harold Bloom for one believed that McCarthy was the completion of an apocalyptic sequence that began with William Blake and continued through Melville, but if you’re the kind of Melvillean who takes as much pleasure in “A Squeeze of the Hand” as in “The Chase,” it is Suttree that will steal your heart.

THE PASSENGER AND ITS “coda” Stella Maris together tell the story of Bobby and Alicia Western, ill-starred siblings whose father helped develop the atomic bomb first at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, later at the Trinity test site in New Mexico. (The Passenger is Bobby’s novel and Stella Maris is Alicia’s.) The Western kids are math prodigies, though Bobby, six or seven years Alicia’s senior, is a mere genius. She is of another order entirely, up there with Nash, Feynman, and Grothendieck, all of whom are name-checked in the novels, as are dozens of other real historical figures from the fields of advanced mathematics, theoretical physics, and philosophy. Alicia is posited to have known and worked with some of them, just as her father is presented as an acquaintance of Oppenheimer et al. Alicia and Bobby were raised largely by their grandmother in a small town called Wartburg, which is not, in fact, a joke. (It’s an hour outside of Knoxville, and if you take State Road 62 to get there you’ll pass right through the heart of Oak Ridge.) The other odd thing about the Western kids is that they’re hopelessly in love with each other.

The Passenger opens in 1980, eight years after Alicia’s suicide at the age of twenty. Bobby is working as a salvage diver based out of New Orleans, though he lives like a drifter. For Bobby, living for something would mean forsaking the memory of his sister’s death, and their forbidden but never consummated love for each other. Or maybe it was consummated? There is a scene late in The Passenger that strongly suggests that Alicia carried and bore a child that arrived deformed and braindead, but it is not clear whether Bobby is remembering this or dreaming it—that is, whether it’s a trauma-slash-punishment that they suffered together or if it’s a conciliatory fantasy of Bobby’s about the horrors that would have awaited them if they’d given in to their desires. (For what it’s worth, Alicia is adamant in Stella Maris that she was always the sexual aggressor, and that the relationship stayed physically chaste at Bobby’s insistence.) Elsewhere in the novel, Bobby recalls watching Alicia perform a solo version of Euripides’s Medea on the floor of a quarry tucked away in the woods.

She was dressed in a gown she’d made from sheeting and she wore a crown of woodbine in her hair. The footlights were fruitcans packed with rags and filled with kerosene. The reflectors were foil and the black smoke rose into the summer leaves above her and set them trembling while she strode the swept stone floor in her sandals. She was thirteen. He was in his second year of graduate school at Caltech and watching her that summer evening he knew that he was lost. His heart was in his throat. His life no longer his.

When it was over he stood and clapped. The flat dead echo halting off the quarry walls. She curtseyed twice and then she was gone, striding off into the dark, the shadows of the trees bowing to her in the light from her lantern where it swung by the bail.

This feels like something out of David Lynch. As is so often the case with Lynch, there’s a non sequitur quality to this scene (the novel contains no other mention of Alicia being an actor) in which an image is so powerful that its intensity becomes its own justification, destabilizing the basic conditions of the narrative even as the force of the disruption draws us deeper into the novel’s dreamworld.

STELLA MARIS IS HALF the size of The Passenger. Set in late 1972, it consists entirely of the transcripts of conversations between Alicia and her psychiatrist at an inpatient mental hospital in Wisconsin to which she has voluntarily admitted herself. Bobby, at this point, has crashed a race car in Italy and is in a coma from which she believes he will never awake. Before he was a salvage diver, Bobby had a career as a Formula Two racer in Europe; I don’t have the word count to get into this, so you’ll have to take my word for it. Oh, speaking of which, Alicia owns a $230,000 Amati violin, and also the Westerns are, um, Jewish. Do with these details what you will or what you can; they are a mere sample of the myriad narrative circles that I simply could not square. Moving on.

Since the age of twelve—specifically, since “the onset of menses,” as we are reminded more times than seems strictly necessary—Alicia has suffered from schizophrenic hallucinations, though they are of such consistency and detail that she can’t be certain they are not in some sense real. She always sees the same troupe of vaudeville players and carnival freaks, some of whom don blackface, and all of whom seem to have been inspired by John Berryman’s Dream Songs, particularly their ringleader, a dwarf with flippers for hands who calls himself the Thalidomide Kid, and at one point makes passing mention of his acquaintance, “Mr Bones.” The ringleader’s name is typically shortened to just “the Kid,” in what can only be a purposeful if baffling allusion to the protagonist of Blood Meridian. The new novels are full of such echoes. Several of Bobby’s Falstaffian reprobate friends could have wandered in from Suttree, and of course Bobby and Alicia’s incestuous love has its own strong precursors: possibly Nabokov’s Ada, or Ardor; certainly McCarthy’s own Outer Dark. (Whatever Outer Dark’s Culla and Rinthy had going between them was not “love” exactly, but it sure did get consummated.)

Berryman, in his “Author’s Note” to the collected Dream Songs, could be talking about Alicia when he describes Henry as someone “who has suffered an irreversible loss and talks about himself sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third, sometimes even in the second; he has a friend, never named, who addresses him as Mr Bones and variants thereof.” The Kid, of course, has a title rather than a name, and though he does not call Alicia “Mr Bones” he calls her things like “Sweetcakes,” “Luscious,” and “Tuliptits.” If he and his crew really are hallucinations then this is indeed a version of Berryman’s talking to oneself in several persons, and/or McCarthy’s own notion of the subconscious as a committee. At one point, Alicia accuses the Kid of reading her diary while she’s at school.

Yeah? I thought I was just some fearful delirium? What happened to that? I guess I should avoid repeating you back to yourself or you’ll claim that I read it in your daybook but let’s just say it was something about a small latterday autoarchon out of the high clavens of dingbatry flapping about in your prenubile boudoir. Well mysteries just abound dont they? Before we mire too deep in the accusatory voice it might be well to remind ourselves that you cant misrepresent what has yet to occur.

The Kid and his cohort (“horts,” Alicia calls them, somewhat tenderly) are creatures whose reality is obviously not objective, but they may not be entirely confined to Alicia’s imagination. Admittedly, psych meds mute them, and in one very funny scene after Alicia submits to electro-convulsive therapy, the horts show up with charred clothes and hair. And yet their feet leave tread marks on carpet; they cast shadows. Whenever they show up after having been away for a while and she asks them how they got there, the Kid usually says they rode the bus. Did anyone on the bus see them, she wonders. The Kid deflects: people see what they want to see. It’s the same sort of thing a shrewd priest might say about angels and demons, spectral operators whose being or nonbeing cannot precisely be reckoned, since any “proof” that they exist would overthrow our working definition of what “existence” is and what its boundaries are, while no absence of proof will ever constitute full proof of absence. It is the indeterminacy itself which must be reckoned with.

McCARTHY IS HUNTING big game and he’s brought out the big guns to hunt with. What he has not done is provide anything resembling a plot through which to reify and explore these ideas in narrative. There is indeed, as the jacket of my galley copy promises in big bold letters, “A SUNKEN JET. NINE PASSENGERS. A MISSING BODY.” And Bobby is indeed caught up in “a conspiracy beyond his understanding,” but it’s hard to convey just how utterly vestigial, even irrelevant, this material is to anything resembling the novel’s real concerns. If Twin Peaks: The Return had you screaming at your TV to get Agent Cooper off the sidelines, or if you think late DeLillo has gotten elliptical to the point of incoherence, you’re going to end up throwing these books across the room.

Personally, I loved Twin Peaks: The Return and I love late DeLillo. (Buy me a drink sometime and I’ll tell you the secret solution to the paradox at the heart of Point Omega.) So I have no problem with McCarthy stepping up to the void for a good long gander. What I take issue with is that these two novels together run nearly six hundred pages, and they hang fire on a host of questions that do have answers. We may never know what lies beyond this vale of tears until we see it—if we see it—and we may never know whether Alicia’s horts are angels, demons, a bio-electrical short circuit, or some combination thereof. (The Kid suggests on several occasions that his presence shields Alicia from far worse horrors lurking in the psycho-spiritual deep.) But sooner or later we should know what happened to the missing passenger on the plane, or at least know who wants to know and why. We should know whether or not Bobby eventually succumbed to his nymphette sister’s advances and whether or not they had a baby that was born dead. We should know why federal agents keep harassing Bobby, first stealing his father’s and sister’s papers from his grandmother’s house, later putting a lien on his car and threatening to jail him for unpaid taxes. The feds want leverage over him and they get it, but then they never exercise it, even as three or four years of narrative time pass by.

It’s hard to say exactly how much time passes because McCarthy is maddeningly imprecise about backstory and timeline. I spent more energy than I’m willing to admit here trying to untangle the question of whether the Westerns had lived with their maternal or paternal grandmother, and whether there were one or two grandmother-characters in the novel, and if so which one was the Jewish one. I eventually decided it didn’t matter and gave up.

The truth is that The Passenger only fails to satisfy when it vamps as a thriller. That’s a promise that just won’t ever be made good. When the novel follows its Lynchian instincts—setting a long scene on a deserted oil rig off the coast of Pensacola, for instance, or allowing Bobby to encounter the Kid (or to dream that he did) on a stormy beach—then its power and pleasures are considerable. It is a novel of set pieces and soliloquies, images and ideas, at its best when refusing to be anything other than its moody, freaky self. Above all, it is a book of evocative surfaces, like a John Ashbery poem, where things we take at first to be windows turn out to be mirrors, and the radical alterity glimpsed in dark glass turns out to be ourselves.

WHAT IS THE RELATION of the unconscious to the conscious mind? How is it that we live with this unknowable at the very heart of the known, this biological operating system that apparently comprehends language but refuses to use it, and what should we do with these otherworldly transmissions that reach us like alien broadcasts from our own deep inner space? These are questions worth asking. The Passenger requires a reader who is patient, a proactive collaborator in the production of meaning, and willing to meet McCarthy where he is. Such a reader will be richly satisfied. As to whether anyone else will be, I truly don’t know.

The Passenger succeeds on the vitality of McCarthy’s prose and the intensity of his vision. I have my quibbles with it, but basically it works. Stella Maris, the “coda” or companion novel, is by contrast a waste of time. I read both novels twice and on the second run-through I read Stella Maris first, because the PR letter I got with my galley said that “the books can be read separately, each enthralling as a stand-alone,” and I was curious to test the proposition—more fool me. Stella Maris has no value as a stand-alone novel. It does not function without a full working knowledge of the contents of the other book, and as a coda it fails to meaningfully clarify, complicate, or reframe any of the myriad unanswered questions that The Passenger leaves us with. It is a work of utter redundancy and irrelevance. The only rationale I can offer for its existence is that it gives Alicia the chance to speak “in her own voice,” as we say these days, but she doesn’t tell us anything we don’t already know, and in fact she already speaks in her own voice in The Passenger. Her conversations with the Kid are presented as italicized interstitial chapters that take up a small but considerable portion of what is otherwise Bobby’s novel.

Her Stella Maris interlocutor, Dr Cohen (another Jew, go figure), cannot hold a candle to the Kid. Their exchanges are two hundred pages of flat banter and name-dropping—Grothendieck, Schopenhauer, Oppenheimer, Berkeley, Feynman, Kant, Jung, Darwin, Quine, Gödel, etc.—almost all of it in unattributed dialogue.

We’re here on a need-to-know basis. There is no machinery in evolution for informing us of the existence of the phenomena that do not affect our survival. What is here that we dont know about we dont know about. We think.

Would that be the supernatural?

I think it would just be the whereof.

The whereof.

The whereof one cannot speak.

Wittgenstein.

Very good.

THERE’S NO REASON for Stella Maris to be this boring; but then, there’s no reason for it to be at all. Rather than punctuate The Passenger, Stella Maris made me second-guess the things I liked best about it, and left me dwelling rather more darkly than I otherwise might have on its lacunae and flaws, because elusiveness and opacity are one thing, but any writer who would publish these two books together on equal footing must just be throwing shit at the wall and hoping for the best. One is reminded that after Berryman won the Pulitzer Prize for 77 Dream Songs he wrote several hundred more of them, and it remains a matter of conjecture where the line was for him between inspiration and compulsion. He would continue to write Dream Songs until his suicide in 1972 (the same year as Alicia’s suicide), even after drawing the work to a formal close with the publication of the complete Dream Songs in 1969. The volume contained 385 entries, which even he seems to have thought was too many; the later movements of the poem are preoccupied by his own struggle to end it.

Lest I be accused of same, let me hasten now to close. In the spirit of indeterminacy, repetition, and ambivalence, I’d like to revise my original question into a statement: Cormac McCarthy is either our most minor major novelist or our most major minor novelist. A final judgment on this matter might be the worthwhile work of a lifetime—I’m sure these books will launch their share of dissertations—but I’ve spent as much energy on it as I’m ever going to. If you, dear reader, figure out what happened to the missing passenger, or if you solve the Jewish grandmother question, please drop me a line. I’d love to buy you a drink and hear the revelations. Otherwise, with “his head full / & his heart full, [Justin’s] making ready to move on.”

Justin Taylor’s most recent book is the memoir Riding with the Ghost (Random House, 2020).