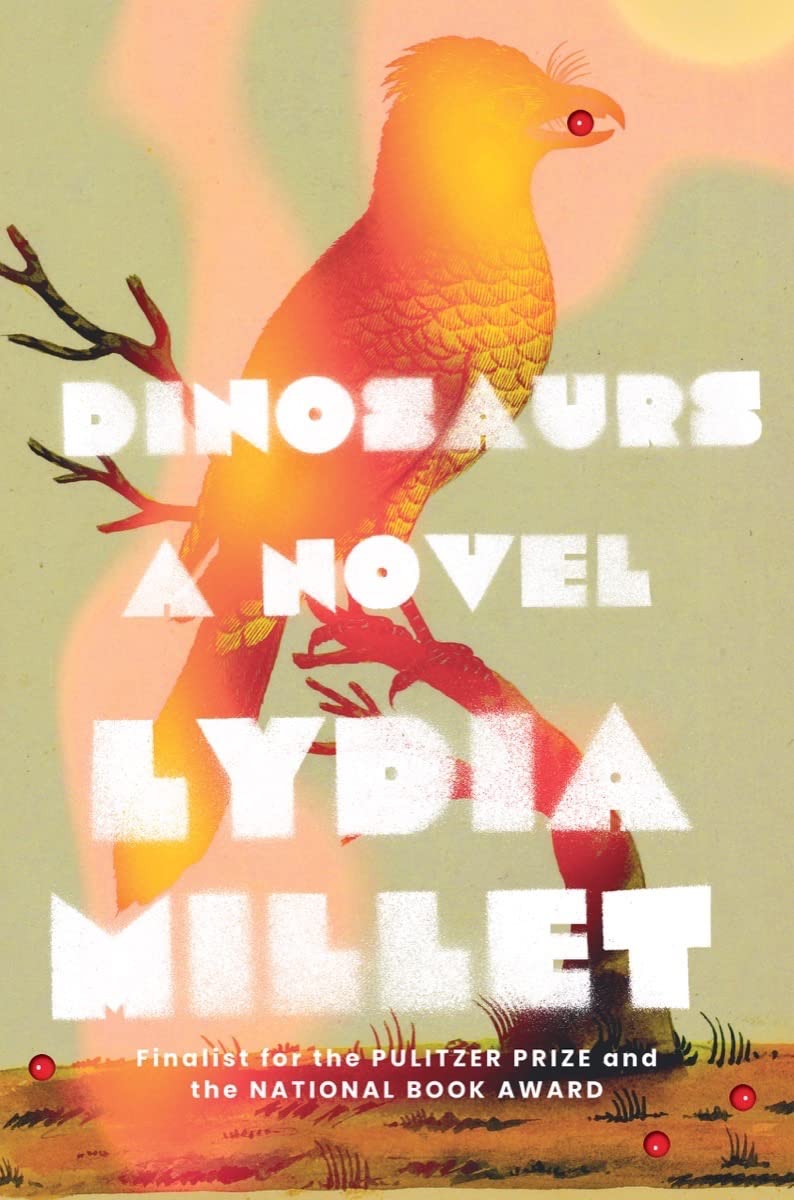

NOMINALLY, LYDIA MILLET’S TWELFTH NOVEL, Dinosaurs, takes its title from the birds that inhabit the Arizona desert in which the book is set. But it also refers to Millet’s protagonist Gil, a kind, aimless man in his mid-forties. Orphaned in early childhood, he inherited a fortune at age eighteen and, when we meet him, is both ashamed of being “disgustingly rich” and fixated on finding the single “best way to contribute.” He’s so terrified of doing wrong that he’s spent his adulthood doing little but clinging to an unhappy relationship, volunteering at a series of nonprofits, and yearning to be good. Dinosaurs studies Gil over a period during which, reeling from a breakup, he moves from New York City to Phoenix and slowly trades his terror of contributing to the world imperfectly for a dedication to contributing in any way he can. Gil’s belated coming-of-age is sometimes bumbling or ridiculous—the man is, after all, out of touch. Indeed, a risk Millet runs—or courts—in Dinosaurs is that some readers may be put off by the idea of taking interest in Gil’s rich-person problems. To make matters trickier, Gil is hardly interested in them himself. Millet’s challenge, then, is to keep readers from following Gil’s example and dismissing his story as one that doesn’t need to be told.

But anybody who’s read Millet—who released her first book, Omnivores, in 1996, and has been publishing steadily since—understands that she thrives artistically on risk. My guess is that she requires it. In her 2014 novel, Mermaids in Paradise, she inserts mermaids into an otherwise realist story; in Sweet Lamb of Heaven (2016), she descends into full, devilish horror; and in her collection Fight No More (2018), she briefly but searingly inhabits the mind of a rapist as he prepares to assault his stepdaughter. It’s a horrific scene, but neither insensitive nor gratuitous. In fact, the story not only earns but needs it. Compared to that risk, or to the infinitely milder one of putting merpeople in a non-fantasy novel for adults (a move Melissa Broder later echoed in The Pisces), writing a fresh novel with a main character who’s a bit of a literary dinosaur should be nothing. Child’s play.

In Dinosaurs’s snappy, vivid first sequence, Gil decides to move to Arizona, choosing it for its sheer distance and “because of some drone footage he’d seen. It wove through the canyons of red-rock mountain foothills, over sage-green scrub and towering cacti.” Gil sells his Manhattan loft, buys a house in Phoenix sight unseen, ships his stuff, and, as if to do penance for how easy his money made the relocation, decides to walk to his new home. It takes five months, but Gil has “nowhere to be and no one who needed him.” After arriving in Phoenix, he speaks of his journey so rarely that it all but vanishes from the novel, the rest of which follows Gil through what seem like the first efforts of his adult life to quell his loneliness. He lets his charming new neighbors Ardis and Ted sweep him into their life, spending evenings with them and afternoons looking after their ten-year-old son, Tom; he volunteers at a women’s shelter that specifically seeks trustworthy “men with a reassuring manner”; he helps a sad-sack acquaintance learn to date; he defends the wild birds on the state land beyond his yard from a mysterious poacher; and he falls in love with Ardis’s friend Sarah. All these developments lead Gil to the long-delayed revelation that there’s more to aspire to in life than harmlessness.

Yet Dinosaurs is more than a simple story of a late bloomer finding out just how much he’s been missing. Millet uses Gil’s growth to explore deep questions of human responsibility—to our communities, our natural environments, and the softer, needier parts of ourselves. But she keeps her philosophical investigation subtle and loose, much like Dinosaurs’s narrative, which she seems to construct while trailing behind Gil, observing him as he stumbles along. Birds are a central motif, and Millet often seems to observe her protagonist like a bird-watcher: distant from her subject, yet fascinated by him to the point of love. Her affection for Gil is plain, as is the respect she affords him. While many writers seem compelled to flay their protagonists psychologically—as if mistaking the ability to reveal their characters’ inner workings for a mandate—Millet gives Gil quite a lot of privacy. She resists explaining why he’s initially so prone to passivity and shame, and offers a similar discretion to her minor characters, too. This approach, frustrating at first, becomes inviting. It also mimics real life: because we have limited access to Millet’s characters, we get to know them more gradually, through what they do and say.

Millet matches the delicacy with which she handles her characters’ inner lives with a noticeably light style. She writes swift, spiky prose that balances descriptive beauty with irresistible momentum—sometimes brutally so, as when Gil observes the hummingbirds in his yard:

They were hovering jewels, some shimmering turquoise and purple, others a coppery orange.

They were also highly territorial, and for the sake of nectar he saw one stab another.

Hard. With its needle-like beak.

Millet is a master of the single-line paragraph. She frequently eschews commas in favor of short sentences that stutter into fragments when Gil gets emotional. One of the sweetest and deftest moments in Dinosaurs is the line in which Gil first recognizes that Sarah wants him, which reads, in its entirety: “It felt like being alive. Only more.” Yet for all the speed of her sentences, Millet’s distant, elegant prose imbues her fiction with a sense of melancholy that keeps it from feeling too urgent or blowing by too quickly. In Dinosaurs, as in its predecessors, Millet consistently evokes the mismatch between the speed of life and the relative slowness of human emotion. Sometimes, she goes a step further, moving beyond humanity entirely to set Gil’s small dramas off against the vast panorama of the desert’s nonhuman life. One of the only lingering effects of Gil’s long walk readers are privy to is that it taught him to notice birds, whose “far-off, swooping dances . . . imparted to him a vague longing.” Millet’s prose often imparts the same.

But she offsets the diffuse sorrow that hovers in Dinosaurs with a finely tuned sense of the absurd. For all the book’s restraint, she lets it be what my grandfather would call a “shaggy-dog story”: not just a yarn, but a bit of a joke. Millet devotes many scenes to Gil’s friendship with Tom, to whom he is equal parts mentor and sidekick; at one point, the two get in a fight with a prissy anti-skateboarding neighbor in their buttoned-up suburb. But Gil’s biggest influence in taking himself less seriously is his New York friend Van Alsten. Van Alsten is a dinosaur like Gil: he played basketball at Yale and married old money. He is also loud, foul-mouthed, unselfconscious—and universally beloved. He devotes his days to playing pickup basketball in Harlem; his buddies admire him for not hiding his wealth and for taking them out to eat after every game. They refer to these meals as gestures of “ridiculous generosity”—not philanthropy, with its air of condescension and detachment, but a simple redistribution of resources rooted in friendship. Over the course of Dinosaurs, Gil learns to embrace a more Van Alsten–esque way of living, which includes learning to give ridiculously.

In the novel’s most dramatic movement, Dag, the man who accidentally killed Gil’s parents in a car crash, starts writing to him, pleading for money. Gil is wounded by much of what Dag says; although he’d thought he had forgiven him, the emails—unnecessarily graphic apology attempts—make it impossible to do so. Gil comes to feel that Dag has no right to contact him at all, let alone ask for his help, but he also understands that Dag needs it. Sarah advises ignoring or blocking Dag’s emails; Gil’s crusty-but-kind lawyer strenuously encourages the same. Gil gives Dag the money anyway, and in doing so, gives himself permission to be illogical and uninhibited.

Toward the end of the novel, Gil plans to ask Sarah to move in with him, and floats the idea of adopting a child together; he dons night-vision goggles and a swat-team outfit—he thinks he looks like a “black cyborg” —to track down whoever’s been shooting the birds behind his yard. Millet allows her scenes to stretch out as Gil himself loosens up. In the quietly cathartic finale, Gil’s swat suit fails to protect him in an altercation with a cholla cactus (“rookie mistake”) and he winds up at his neighbors’ house, high on Vicodin and babbling about insects while Sarah tweezes hundreds of barbs out of his skin. He feels “like a child, standing there shirtless in front of everyone,” Millet writes. “Exposed and hurting, with one arm raised over his head.”

It’s a comic ending, told slowly and gently. For the first time, Gil has surrendered to his own needs. He’s still disgustingly rich, and he’s still got no job or obligations. But he’s learned to ask for help, to relax, and to laugh at himself. Readers are free to laugh with or at him, though it’s clear where Millet stands: she’s given Gil a community. He’s more tied down in life—and so much happier for it that he basically turns into the speaker of the Band song “The Weight,” going around asking people to let him share their burdens. In studying Gil as he seeks some weights, Millet invites readers to reframe our own lives a little, reassess what constitutes luck. Nobody wants to be weighed down too much, but it beats the alternative.

Lily Meyer is a writer, translator, and critic.