IT IS MY FAULT and only mine if I keep Gordon Matta-Clark as a personal Jesus, but the story flies. Matta-Clark died, way too early, at the age of thirty-five in 1978, and spent a chunk of his time slicing up abandoned buildings, which is very Jesus-y. One of his building cuts has become a permanent part of Manhattan’s west side—of that, more soon—and he even contributed to New York’s proudest category of impermanence: the restaurant. (RIP Food, Soho, 1971–1989.) Matta-Clark was tuned to frequencies prophetic in nature and number: the glow of decay, the need to befriend ghosts, and the spiritual value of free, the only real price. A theoretical—they called it “behavioral” at the time—architect and conceptual artist of all tools who punctuated houses and freestyled with a saw, Matta-Clark would not likely have walked into the bathroom-coke and podcasts holding cell of today’s art world, had he lived. (He would have been seventy-nine this year.) In my limited but acute imagining, GMC would have been the éminence grise of culture jammers, advising people to let ideas grow mold and break into whatever isn’t locked up. The most sanctified thing he did, after all, was to make art that disappears. As William James points out in The Varieties of Religious Experience, unseen things are central to religious attitudes. That which we believe in, the objects of our consciousness, “may be present only to our thought,” but “the reaction due to things of thought is notoriously in many cases as strong as that due to sensible presences.” What GMC’s work shares with a religious practice is the idea that exegesis is more the point than mere witnessing.

Matta-Clark is strongest in outline, and this is exactly what David Hammons turned him into. Hammons’s 2021 work Day’s End is a stainless-steel tracing of a warehouse that used to stand on Pier 52, the site of the first Day’s End, Matta-Clark’s 1975 piece. I love the Hammons reimagining because it demands the same kind of thought as the original, while only hinting at Matta-Clark’s cuts, a religious ranking of spirit over matter. Matta-Clark went into this abandoned pier on the west side of Manhattan and cut holes in the structure, largest of them all a massive, leaf-shaped crescent in the far wall. This “cat-eye-like ‘rose window,’” as he described it, faced the Hudson River and was not visible to passersby. Matta-Clark saw Day’s End (also known as Days Passing) as an “indoor park,” and it lasted longer than most of his building cuts, more than two years. Since then, the original work has lived as the subject of a film and a set of photos. What Hammons designed makes no reference to the shapes Matta-Clark cut, so it technically refers only to the warehouse, originally owned by a railroad company. But this is all Matta-Clark did anyway: ask us to think about a building. He is now a fixture of NYC, through Hammons, as the new Day’s End is maintained by a trust.

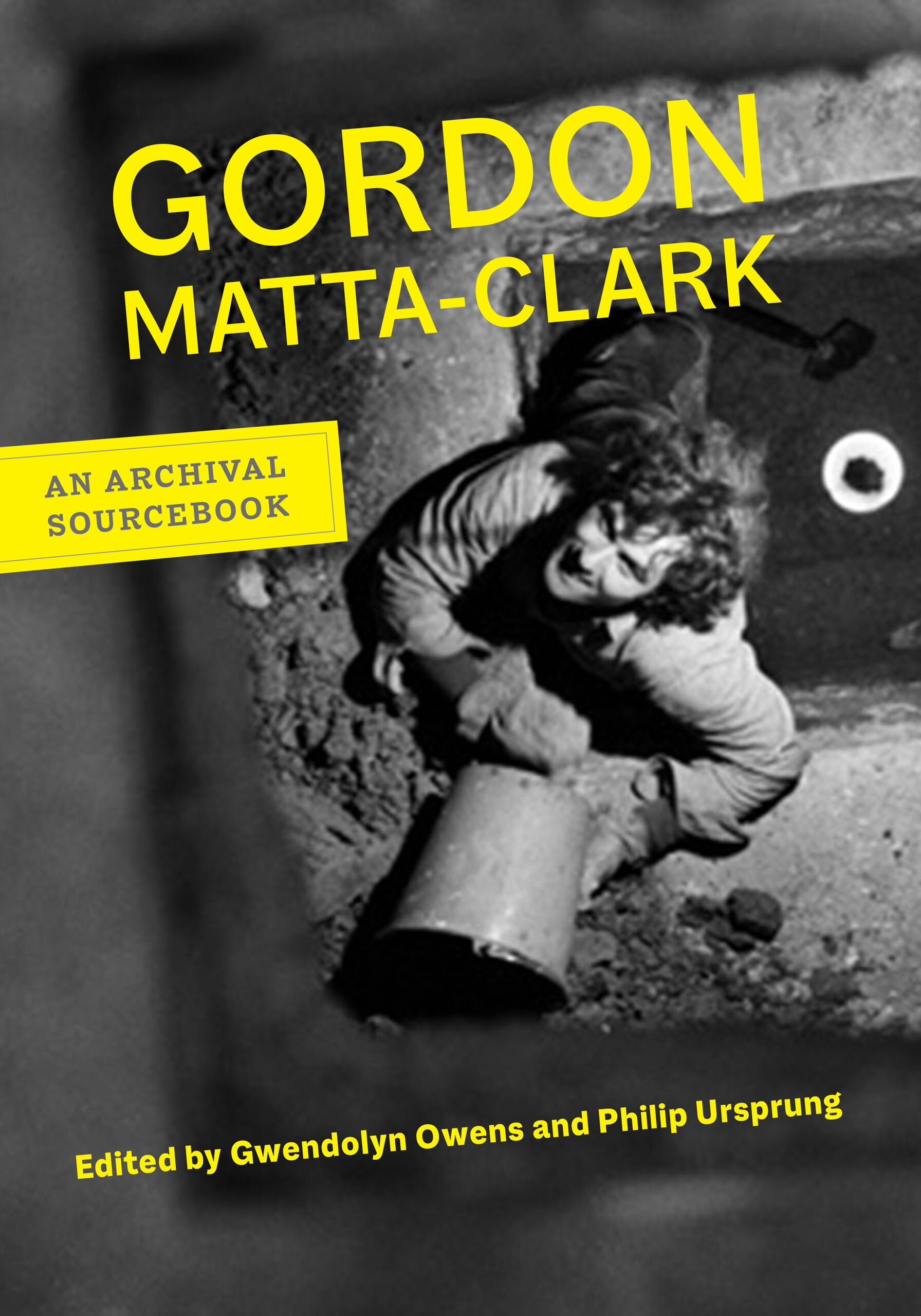

There is a beautiful photo of GMC sitting on a wooden platform and carving the outline of the Day’s End wall hole in Gordon Matta-Clark: An Archival Sourcebook, edited by Gwendolyn Owens and Philip Ursprung. These two scholars scoured the Gordon Matta-Clark Archive in Montreal and did a remarkable job of stitching together letters and scraps of paper to convey what GMC thought about and how. Since he didn’t leave behind a vast series of artifacts, books like this may be how GMC “happens” more than he happens in any gallery. Hearing so much of Matta-Clark’s own voice here gives us that much more to work with.

The father to Matta-Clark’s son and holy ghost combo was Roberto Matta, Chilean Surrealist and art-world heavy. In 1971, Gordon wrote to him, thanking him for a “fabulous gift” that helped him through “another difficult period of rent and expenses.” The younger Matta wished he could “realize a few sales on my work, but it is pretty hard for others to accept.” He goes on to explain why this is so, and summarizes much of what he ended up doing in the years before his death.

I have worked with some fairly unusual materials and operations in making sculpture, making curious preparations out of food, seaweed, and vegetable matter. I have had something less than a rave response to these initial inventions—but I keep confronting new situations all the time. In the past few weeks I have done my first outdoor piece in New York, my first theater performance, my first slide lecture, my first lecture to college students in another city. . . . So, though I am not sure what it all means, there is little time to lose in doubt and hesitation. Of course I sell nothing and am completely out of the conventional gallery system so everything is experimental . . . which means that I am still learning in a real situation.

In a 1974 interview, Liza Béar asks the artist about his tendency to modify buildings about to be demolished—in this case, the small home in Englewood, New Jersey, that was the object in Splitting. GMC describes it as “substandard housing in bedroom suburbia near the Lackawanna railroad.” Béar asks, “But aren’t you partly drawn to something that’s about to collapse?” My Jesus engine kicks in here, as I expect him to talk about the kingdom of heaven in the ruins. That’s not what happens. GMC tells Béar that he knows these situations “bring up romantic associations” but that he chooses buildings largely based on expediency. “I’d much sooner do something right across the street,” he says. “I’d just as soon deal with something that’s brand new, crisp, and not at all ready for the ax.” Which is not to say he was against magic, or at least the charm of the unexpected. “One aspect of buildings I’ve worked on which may be considered romantic is that they’re in unexpected locations, but the unexpected is not dependent on the particular disintegrated quality that they have.”

These qualities are evident in the photographs he made in several abandoned buildings for Bronx Floors (1972–73), a work that was designed to live beyond the life span of the houses being cut. If art is supposed to make us look at what already exists and absorb its contradictions without the fear that consciousness brings, his building cuts are among the finest art of the twentieth century. These buildings—to whom did they belong? The great architects of the late nineteenth century? To the people who last lived there? To the gallery exhibiting Bronx Floors? To Matta-Clark? The photos show a geometrically gorgeous series of receding frames, a parallelogram punching downward through lathe work and rubble, reminding us both how impressive and fragile the city’s infrastructure is, how easily it is converted into a perspectival game. Kids were jumping out of windows onto mattresses in the South Bronx. (See Manfred Kirchheimer’s 1981 film Stations of the Elevated for footage of exactly that.) Gordon jumped right through the center of these homes, and none of it was sponsored by Smirnoff or Squarespace. As he told Béar, “I just wanted to get back to whatever the empty rooms were made of, like the layers of linoleum on the floor, or whatever there was of surfaces.”

The Béar interview is, by itself, one of the single best introductions to Matta-Clark and his thought, but there are other equally valuable documents here. We can imagine that this scrap from 1972 was deadly serious because GMC would have done both of these things: “Plans to break / into the / Democratic National / Headquarter in / Washing D. C. / Plan to break / into a / A road runner / breaking the / speed limit.” In 1976, he told Donald Wall, “One of my favorite definitions of the difference between architecture and sculpture is whether there is plumbing or not.”

What makes this my favorite Matta-Clark book to date is that it is told primarily in his voice, through letters he wrote and interviews he gave. His short life and shorter career has, to date, induced a sort of protective vomiting in researchers, who often include everything they have found of his, or thought about him, in order to balance the void he left or possibly fully explain what made this enigma so important. More is not more with GMC, though. Owens and Ursprung are prudent, and have arranged Sourcebook chronologically, selecting texts from each year, carefully; also, their brief editorial incursions are welcome. This one note from the editors is simple but as illuminating as a string of LED: “A graduate of Cornell University’s School of Architecture, Matta-Clark distinguished himself as an outstanding student. Yet to some friends he presented himself as someone who barely made it through the program.” GMC operates in a weird trench; he came from privilege and yet worked outside most of what it might have provided him. His Marlboro Man via Marx routine probably helped him more than his last name, though it’s impossible to tell, especially in an art world that had yet to go through the financialization of the ’80s. Had GMC had the opportunity to upscale his work to stock-market heights and start breathing in tandem with the gallery cycle, he well might have. (The Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark joined the David Zwirner Gallery in 1998.) GMC was hardly doctrinaire or predictable; nor was he, the careful reader will have noticed, any kind of Jesus. He was an artist, a hard-working and extremely flexible one. When Donald Wall suggested that the residue of the Splitting house might end up in the Hirshhorn, Matta-Clark gave a response that works as a placeholder answer to “What would Gordon be doing in 2022?”: “I mean, if someone in the museum was really interested in my work,” Matta-Clark said, “they would let me cut open the building.”

While working in 1977 on Descending Steps for Batan, a tribute to his brother Sebastian (Batan), Matta-Clark wrote to Jane Crawford (soon to be his wife) on a “glossy” card: “Despite my serious attempt at heavy underground imagery it all turns pretty (as in photos) or funny—what a perfectly ridiculous way to make a living (is it a way to make a living?).” There are so many delightful notes here, like this answer GMC gave during an exchange in 1978, about the reactions to Splitting. “I received a lot of mail, much of it positive but among the angry letters was one from an architect who said I was violating the sanctity and dignity of abandoned buildings by interrupting their transition to ruin or demolition.” And then: “Why hang things on a wall when the wall itself is so much more a challenging medium?”

Sourcebook improves the more time I spend with it. There is so much that was previously unclear that the archives have made at least clearer, if not definitive. Matta-Clark came from art royalty, but that doesn’t seem to have provided a financial cushion for him. In one letter, he asks his father for money, and much of the correspondence sees him looking to artistic organizations around the world for money and staffing for his various projects. (His budgets are small and he emphasizes that he is “flexible.”) In February of 1978, only months before his death, he talks to Judith Russi Kirshner of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, for whom he’s recently completed a building cut. (The building was attached to the MCA and torn down soon after Matta-Clark chopped it up.) “My posture has been unemployment, artistic unemployment for years, so that turning things down really isn’t my habit.” Anarchitecture was, as Owens and Ursprung write, “loosely defined as architecture of the accidental or the mundane,” and this term “would come to be used in connection with the whole of his oeuvre.” There was supposed to be an Anarchitecture show at the 112 Greene Street gallery, and an invitation card was printed, but there are “no reviews or firsthand accounts to confirm that the exhibition took place,” as Ursprung and Owens write. The notes for potential Anarchitecture pieces he sent in letters to Carol Goodden are perfect conceptual pieces in themselves, as seen in this “word work” he sent to Goodden in 1973:

Word Works Part II

A) The space it takes to house enemies

The space it takes to house lovers

The space it takes to dodge a bullet

The space it takes to remove a bullet

The space it takes to remove your hat

The space it takes to remove your house

The space it takes to remove your house

GMC was, possibly, as much performer and priest as he was artist, someone who depended on the fleeting charge of human presence to illuminate and complete his work. The vitality of the passing moment (and the passerby) is not a friend to the art market but it was his muse. As he told Donald Wall, “My work is performance-based but not intended for other people to watch. It’s very much for a private audience of one—myself. And the house, of course.” Should you succeed in collecting anything of his, don’t worry—you haven’t. As he said about those who collect the debris from his cuts, “Amazing, the way people steal stones from the Acropolis. Even if they are good stones, they are not the Acropolis.”

Sasha Frere-Jones is a writer and musician from New York. His memoir, Earlier, will be published in the fall of 2023 by Semiotext(e).