IN 1912, THE SWEDISH ARTIST-CLAIRVOYANT Anna Cassel recorded the following message, crystal-clear instructions from a spirit guide, in her diary: “First, allow yourself to have dreams and then visions and colors and numbers, letters and images. Make a careful note of everything. It is of utmost importance to be thorough in your description.” Cassel was a lifelong friend of the spiritualist painter Hilma af Klint (and very likely more than a friend, for a time), as well as a close collaborator. In af Klint’s notebooks, Cassel’s group of 144 enthralling small paintings, her dutifully thorough description of a primordial story, transmitted to her from the astral plane, is referred to as “The Saga of the Rose.” The cycle was meant to serve as both a prayer book for the artists’ devout Christian-occult community (whose all-women initiates totaled just thirteen) and a history of the world.

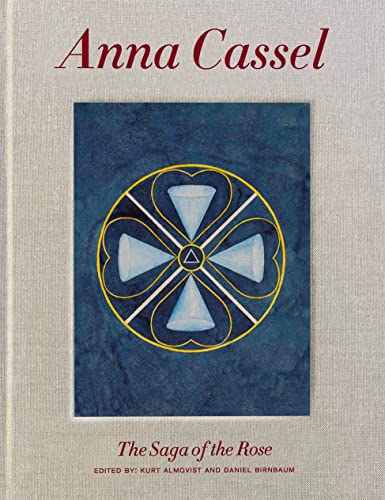

Discovered in the archive of the Swedish Anthroposophical Society in 2021, the sacred illustrations are reproduced in this solemnly beautiful clothbound book, its hushed design aligning with Cassel’s glyphic and celestial compositions. Fastidious and fervent, aware of trends in painting and Modernist decorative arts, Cassel favored botanically inspired lines, distilled geometries, and a crepuscular-or-witching hour palette to capture the strange wind and cold light of a particular metaphysical space. The saga’s figurative and allegorical entries complement her numinous approach to abstraction. Tarot card–like watercolors—a swan and a chasm-spanning bridge, for example—offset the floating runes, glowing pyramids, and stark Rosicrucian imagery elsewhere.

Though the book is not rushed in its appearance, it’s delivered with the caveat that research into the vast output of Cassel and her complex, intimate milieu has only just begun. The luxe edition comes on the tail of new information (detailed in the editors’ accompanying essays) proving that the earlier, large-scale series “Paintings for the Temple”—the subject of major museum exhibitions, on which the posthumous superstardom of af Klint is based—was, in part, conceived and executed in partnership with Cassel. And significantly, both women’s writings indicate that other works attributed to af Klint were made collaboratively by various combinations of their circle’s members.

The revelation of these material and spiritual contributions challenges not just the chronology and composition of the canon but also the patriarchal notions of individual authorship and singular genius at its heart. Only recently, af Klint’s work (or what was thought to be hers) upset the art-historical timeline, placing her ahead of solitary male artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich as the inventor of non-objective painting. Now, that recently revised narrative of twentieth-century European painting is cast in doubt. It was not a lonely female savant but a visionary women’s collective, founded on romantic and religious bonds, in intimate contact with the spirit world, that arrived at pure abstraction first.