IN OSCAR WILDE’S “The Critic as Artist,” Ernest cajoles his friend Gilbert off the piano bench and into an armchair for a discussion, as the original title of the mock-Socratic dialogue would have it, of the “function and value of criticism.” Over the course of an evening passed in the library of his Piccadilly town house, Gilbert, an incorrigible contrarian, pours glass after glass of epigram, paradox, and hyperbole down the throat of Ernest’s received ideas until they can no longer stand up.

It is probably unwise to attempt to derive anything as definitive as a “statement of Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy” from so thoroughly ironic a text, but Gilbert does advance a coherent theory that not only is art a “self-conscious, deliberate” criticism, “criticism is itself an art . . . both creative and independent.” Criticism, he argues, stands in the same relationship to a work of art as a painter does to a model or a landscape; the critic treats a work of art as a “suggestion for a new work of his own, that need not necessarily bear any resemblance to the thing it criticizes.” Having been put into a particular mood by an artwork, the critic’s aim is simply to create another one for the reader. “Creative criticism,” as Gilbert calls it, has survived into the twenty-first century as a minor literary mode, embraced, to varying degrees of explicitness, by such writers as Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Susan Sontag, Wayne Koestenbaum, and the Dublin-born, London-based essayist Brian Dillon.

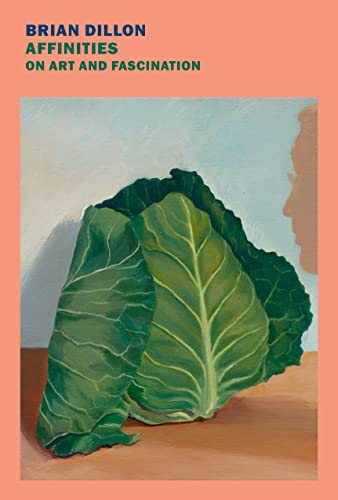

Dillon’s Affinities, the third volume of an informal critical trilogy, begins where Gilbert leaves off: “I am tired of thought.” Following Essayism (2017) and Suppose a Sentence (2020), Affinities collects Dillon’s short prose writings on thirty images, arranged in chronological order, from an engraving of the eye of a fly in Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) to a photograph of a rose from Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance (2001). Many of these pieces have previously appeared in venues such as Artforum, Frieze, the London Review of Books, and Cabinet, where Dillon is the UK editor. Connecting like a “loose seam” his considerations of art photographs, family photographs, scientific images, and stills from films and theatrical performances is an “episodic” investigation into the titular concept in three senses. First, the affinity a critic has for various works of art; second, the affinities various works of art have with each other; and finally, the affinity Dillon has for the term itself.

“I found myself frequently using the word affinity,” he writes, “and wondered what I meant by it.” Taken together, the book’s ten “essays on affinity” can be described as a kind of manifesto for an anti-critical criticism. Dillon subjects the word to a familiar array of para-academic procedures. He considers its etymology; its relationship to cognate concepts like fascination, appreciation, sympathy, attraction, the crush; its lowly position in the hierarchy of accepted aesthetic categories; the history of its usage in the discourses of literature, science, and theory; its metaphorical relations to images of, for example, fog and light; its unassimilability to the norms and procedures of scholarship; its noncognitive status as an affective atmosphere or mood. Much like Dillon himself, who supplements his freelance work by teaching creative writing at Queen Mary University of London, “affinity” is perched on a wire between the technical jargon of the English department, where interpretations are advanced and arguments in support of them are defended, and the demotic vocabulary of the social cataloguing site, where an algorithm sorts objects according to their similarities, and users are content to simply “like” them. “When I wrote affinity in a piece of critical prose,” Dillon muses, “perhaps I was trying to point elsewhere, to a realm of the unthought, [the] unthinkable, something unkillable by attitudes or arguments.”

Like Dillon, I am a partisan of creative criticism, but when I am told that something is unkillable by argument, I reach for my revolver. If nothing Dillon writes “pursues an argument” or is “built to convince,” it is, in part, an attempt to make a virtue of the limitation he confesses in Essayism: “I was and remain quite incapable of mounting in writing a reasoned and coherent argument.” He associates argumentation with the academy, whose procedures of making “judgments and distinctions” are foreign to a sensibility that prefers describing objects and noting correspondences between them. His memories of the academy are a source of “shame,” and the institution functions as a kind of superego for him, whispering in his ear, as he writes Affinities, more than two decades after he received his PhD from the University of Kent, “Do you call this criticism? What is wrong with you?”

Say what you will about the academy, the reason that pursuing an argument is a cornerstone of critical practice is because arguments are at least intersubjectively available to readers, who may be persuaded by them or not. (As for the use of etymology as a valid means of elucidating a concept, the word “critic” is derived from the Greek kritikos, “able to make judgments,” from krínein, “to separate, decide,” from the Proto-Indo-European root krei-, “to sieve,” thus “to discriminate, distinguish.”) It never becomes clear what particular advantages “affinity” has over its cognate concepts—what affinity, rather than attraction or liking, allows the reader to see—to anyone but Dillon. Being a private matter, his affinities are not, properly speaking, enthusiasms. Dillon seems perfectly indifferent to whether his reader shares his, and the essays in Affinities, which are at best informative, provide little encouragement to do so. When Dillon writes that affinity, like a crush, “exiles us from consensus, from community,” I cannot help but wonder who “us” is supposed to include.

Put differently: affinity begs the question. Since sharing an affinity with another person is a matter of chance—although a rigorous sociology of taste would suggest otherwise—learning that Dillon has an affinity for an artwork tells us something about Dillon, not the artwork. This is why the successful essays in the collection are the personal essays—about his childhood migraine auras, his aunt’s collection of photos of her house, the Charismatic Renewal movement in the Catholic Church to which his mother briefly belonged, his viewing of the Brideshead Revisited TV series on Channel 4 as a Dublin teenager with “anglophile tendencies” and dandyish pretentions in the mid-’80s. Here at least we are treated to something we could have not learned elsewhere, and do not learn in most of the essays: how Dillon came to have his particular affinities.

The exclusive focus on affinity has other limitations. Aside from the academy, we never learn what repels Dillon. Nor do we ever learn what he is ambivalent about, though to understand a concept it is surely just as important to understand the limits of its application, and what lies beyond them. Affinities are often only “temporary,” Dillon acknowledges, but we are only treated to a single case in which he describes the familiar aesthetic experience of having the terms of one’s appreciation change as one’s taste develops and as one acquires new experiences and knowledge. Not coincidentally, it is the strongest essay in the collection. “Hope, fear, resignation, regret—how very middle aged,” Dillon reports of what he gleans from his “seventh or eighth viewing” of Brideshead Revisited early in the third decade of the twenty-first century. “I wonder now if Brideshead . . . was always a lesson for me, frustrating and revealing, in how riven and contradictory a work of art could be.” “I had to read it against the grain,” he continues, “turn a story of aristocratic inner-war English life into a model for escaping ordinary Irish expectations in the 1980s.”

When Dillon does criticism he “simply get[s] into a mood about the thing [he] is meant to be writing, and pursues that mood until it is exhausted.” This is perhaps not so different from what anyone, even academics, do when they write, although it is unduly coy about the role played by generic constraints, house styles, editors, and indeed, changes of mood in the final shape taken by a piece of critical prose. In support of this method, if you want to call it that, Dillon invokes the authority of Oscar Wilde and the “throwaway theory of mood” he finds in “The Critic as Artist.” Dillon “takes solace”—the tone of the phrase is characteristic—in the precedent set by Wilde’s dandyish approach to criticism as an art form in and of itself.

Yet interpretation—reading an artwork against the grain—never lost its centrality to Wilde’s concept of criticism. What makes a criticism creative and independent art is precisely that it adds something new to the artwork that isn’t obviously there (or there at all) and in so doing justifies its reason for being written in the first place. In his treatment of most of the images in Affinities, however, Dillon largely eschews interpretation—since this would require him to claim something about the image and, in turn, justify that claim in the face of potential disagreement—in favor of mere description, sometimes with tentatively phrased speculation, for example, about the thoughts of the subjects, as when he wonders whether the girl in a photograph by Helen Levitt “might be looking toward the future.” Dillon objects, on principle, to the use of “mere” as a qualifier, but what else should one call description that serves no further hermeneutic, rhetorical, narrative, or philosophical function?

In the right hands, ekphrasis can, of course, be a powerful tool, as T. J. Clark’s sustained attention to Poussin in The Sight of Death demonstrates. Dillon, citing the example, nonetheless elects to forgo Clark’s “protracted and intense gaze” in favor of a “slightly stupefied” one that moves from image to image once his attention switches elsewhere, his mood is exhausted, or the deadline approaches. Not that there is anything to object to in Dillon’s prose style—except for its lack of ambition. Readers of the bravura performance of syntax that opens Suppose a Sentence will know that Dillon is capable of some impressive finger work. In Affinities, he turns in a few pretty passages—such as when the Comte de Montesquiou’s mustache is described as having been “waxed into vicious points” in the essay on Claude Cahun, or when “a stream of transparent glass or plastic letters floats” out of photographer Francesca Woodman’s mouth “like ectoplasm”—but he keeps the soft pedal on for most of the concert.

Underlying Wilde’s theory of mood is a deeper question of the critic’s temperament. Dillon’s could not be more different from Gilbert’s. It is not simply that Dillon is sincere, whereas, for Gilbert, “a little sincerity is a dangerous thing, and a great deal of it is absolutely fatal.” Nor is it that Dillon is self-effacing, whereas, for Gilbert, “it is only by intensifying his own personality that the critic can interpret the personality and work of others.” It is fundamentally a different attitude toward mood itself. What Wilde values in creative criticism is capaciousness: its capacity to deliver “complex multiform gifts of thought that are at variance with each other,” which “fully mirrors man in his infinite variety,” and can “give form” to “every mood.” Dillon, by contrast, rarely ever departs—in his selection of images, in the dour tone of his short sentences—from the single mood for which he seems to have a genuine affinity: melancholy.

In the end, Dillon does not seem to mean anything different from what anyone else does when they use the word “affinity.” Perhaps the sentence should instead be read as: all writers have tics, why do I have this one? As with all repetition compulsions, the answer turns out to be a personal one. The first time “affinity” appears in the trilogy is in an early passage in Essayism, where Dillon notes that the essay genre “seems to have a peculiar affinity with” the list. (The word “peculiar” is another tic: he frequently uses this word, as well as the adjectives “weird” and “curious,” to modify his responses to art, as though these required a performance of surprise in order to receive permission to be expressed.) Dillon is certainly fond of lists. Essayism opens with one (a list about the subjects of famous essays), as does the passage I have just quoted from (a list of synonyms for the word “list”). He praises Sontag for drawing up lists of books, slang, recherché vocabulary, “likes and dislikes.” Suppose a Sentence is a commonplace book or cento; Affinities is a kind of photo album. It does not fail to note the lists of the fourteenth-century alchemist Pseudo-Geber, Diane Arbus’s list of places she wanted to photograph, Charles Eames’s list of advice for design students, or the list of “ordinary heroes” compiled by the Victorian painter G. F. Watts. It concludes with “a partial list (or imaginary collage) of images that are not mentioned and do not appear in this book, but will not leave the mind.”

The psychology of the list-maker is that of the collector; lists are, after all, collections of words. In the Arcades Project, in what is undoubtedly the canonical statement on the psychology of the collector, Walter Benjamin writes: “Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: he takes up the struggle against dispersion.” Interestingly, since Benjamin’s essays are frequent reference points throughout the trilogy, and since Affinities is a book that seeks to resemble the collagist Arcades Project on a personal rather than civilizational scale, he does not consider this particular passage, which continues: “The collector . . . brings together what belongs together; by keeping in mind their affinities and their succession in time, he can eventually furnish information about his objects.” Dillon claims that the personal pronoun of the essay genre is “dispersed” across thousands of bodies over hundreds of centuries; Essayism is a way of bringing them together again. Just as what brought the sentences of Suppose a Sentence together was that a “remarkable number seem to be about death and disappearance,” what brings the photographic images of Affinities together is “a state of bodily between-ness verging on dissolution.” Blurred or partial images of faces, scenes of ruin and destruction, and the abyssal unintelligibility of the cosmos are what seem to “impinge” on Dillon’s melancholic eye.

If the connection between writing and depression is a cliché, as Dillon remarks in Essayism, the connection between photography and death is no less one. (It is explored in both Barthes’s Camera Lucida and Sontag’s On Photography, the two obvious precursors for Affinities.) Melancholy is tolerable in a writer to the precise degree that one cannot be certain what its specific cause is. Unfortunately, the motive underlying Dillon’s three collections is fairly transparent: the death of his mother, of scleroderma, after years of depression and mental illness, when Dillon was sixteen, and the death of his father, five years later. This furnishes the subject of Dillon’s 2006 debut, In the Dark Room—also a book about photography. The story is revisited at lesser length in “On Consolation,” an essay in part about his parents’ reading habits and in part about his twin discovery of Camera Lucida and his vocation as a writer in Essayism. It is mentioned again in the chapter on Elizabeth Bowen in Suppose a Sentence. In Affinities, Dillon writes: “One day I will stop writing about this, rehearsing the bare facts for anyone who will listen, attaching her life and her death to half the things I have to say about books and music and art and stray photographic scraps in which as it happens she has no part.” This furnishes us with our best clue as to why the collector Dillon is drawn to “affinity,” the concept in which he finds “something unkillable by attitudes or arguments.”

The pathos of the collector, however, is this: no collection can ever be complete. Dillon’s final essay on affinity, consisting of a list several pages long, on what did not make it into the book, is itself only partial, and necessarily so. “In every collector hides an allegorist, and in every allegorist a collector,” Benjamin remarks. Dillon can add indefinitely many new items to his collection, because in each one, he will always see the same thing. The way out of this vicious circle is not to think of argument, as Dillon does, as something that, by establishing the truth of the case, kills discussion, but rather as something that, by risking disagreement and difference of opinion, makes one’s thoughts and one’s moods available to others for further discussion. In other words, to think of an argument as Wilde thinks of an interpretation: as something that is never final.

Let’s give Wilde the last word then. When Ernest is on the verge of conceding the argument, Gilbert interrupts him: “Ah! Don’t say you agree with me. When people agree with me I always feel I must be wrong.”

Ryan Ruby is the recipient of the 2023 Robert B. Silvers Prize for Literary Criticism.