ONE STURDY WAY TO UNDERSTAND WRITER and director Henry Bean is as a specialist in the study of extremely bad behavior. His best subjects are the worst: self-hating havoc-wreakers, or the “I Suffered Complicated Trauma and Now the World Has to Deal With It” type. Populating his catalogue of asshole picaresques—rich with vicious couplings, drunken confrontations, alfresco autoeroticism—are a secretly Jewish neo-Nazi played by a skinhead Ryan Gosling (The Believer, 2001), a sledgehammer-and-baseball-bat-wielding vandal (Noise, 2007), a sexy serial murderess (Basic Instinct 2, 2006), and the protagonist of his only novel, a writer who presents his latest project as a kind of homicide. “He pictures a brief affair that begins with her feeling whole, solid, full and ends when her life and character lie in ruins.”

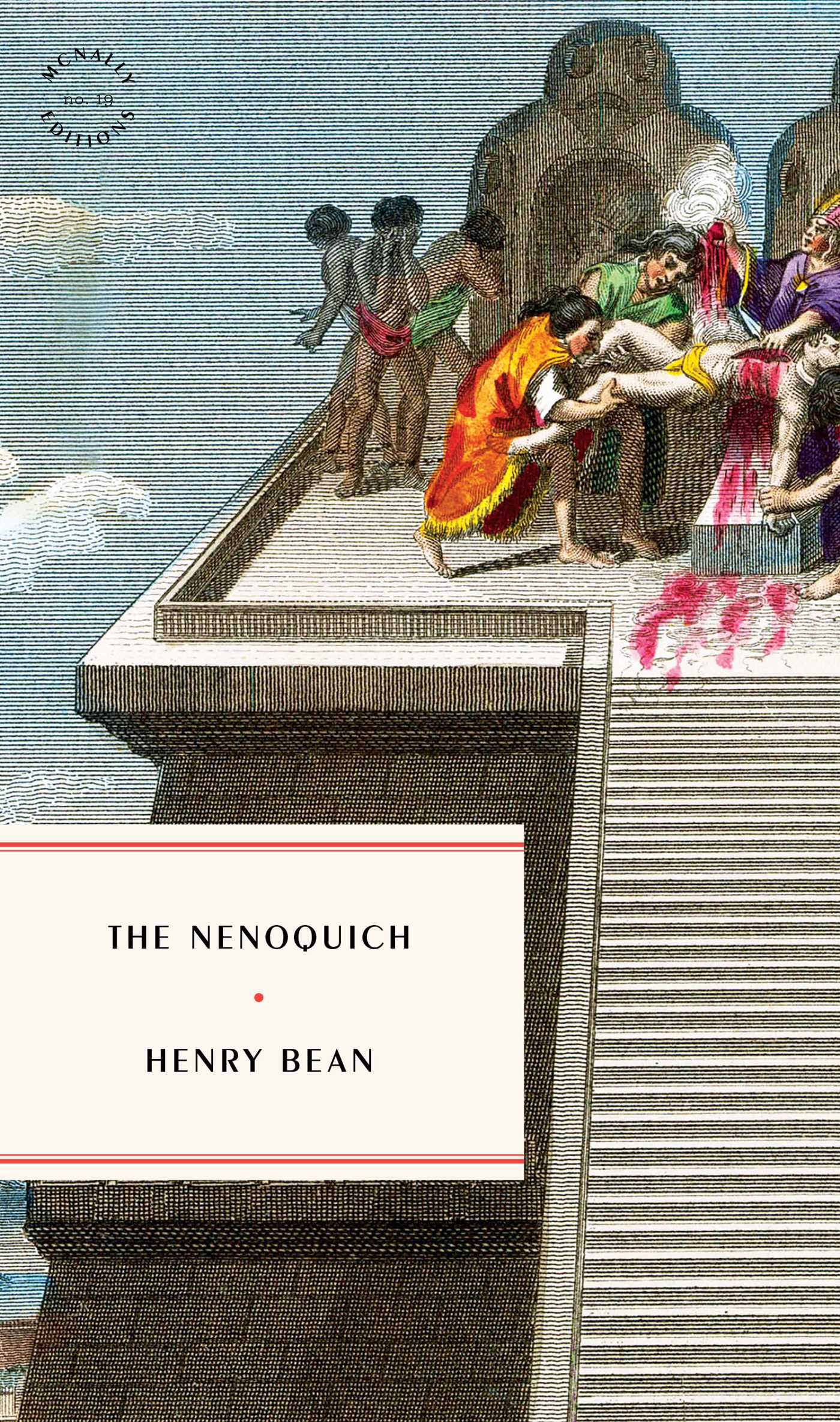

So goes the rank voice of Harold Raab, the diarist-narrator of The Nenoquich, written in the ’70s and first published in 1982 as False Match. The recherché title Bean preferred all along, now restored to the reissue by McNally Editions, refers to an Aztec term that translates roughly to “worthless person” or “will never amount to anything.” This gives us poor Harold: a twenty-six-year-old writer at work on an unspecified masterpiece from his bedroom in the rental he shares with three lefty housemates, each “seized by a fit of despair” over their prospects in life. As sluggardly and shapeless as Berkeley circa 1970—a whiff of the freshly dead hippie heyday still in the air—Harold watches as his formerly revolutionary-minded friends abandon him and the city to “topple over the ridge into Los Angeles or New York.” In the purgatory meantime, his pod talks “about mothers or capitalism or technology (a different trip every night)” until they adjourn into separate bedrooms through which sounds (sex, arguments, the flipping of a page) seem to travel too well. The days groundhog until one evening when Harold, eavesdropping, becomes torqued by a passing reference to a married woman he’s never met.

This is all sympathetic enough. Harold could really use a muse—someone to marshal the fog of his compulsive writing habit (“Despite my efforts,” he drones early on, his project “grows in size without any refinement of shape or purpose”), to redeem his general aroma of insignificance (“I was superfluous even to myself”), and to distract him from his near-estrangement from his family. Sheer mention of Charlotte Cobin, normie Cali dreamgirl (“too tall, too young, too cheerful, too frank”) seems like a salve. Harold, who sometimes writes about himself reflexively in the third person, suddenly “has fantasies of degrading and humiliating” Charlotte. Total stranger and part projection, she makes for perfect prey, and ten pages in, Harold’s diary becomes as Parnassian as Kierkegaard’s Johannes in Diary of a Seducer, or as jaundiced and designing as Elliot Rodger in his manifesto, My Twisted World. “He would force her to have pleasure,” Harold declares. “She would be lost.” We wonder when and how—and even if—she’ll be destroyed.

The Nenoquich asks us to treat the title as if it comes with a question mark. Is Harold a zero? Is worthlessness his fate, or is it volitional? And what would it take for him to amount to something? For Harold, Charlotte is precious not only as a literary subject, but also as a victim on which to test the exploitative equation wherein one’s meaning expands when someone else is made smaller.

A diary is a flexible formal framework, and Harold’s is a confessional and a ledger, nakedly documenting his invented rules of conduct for the affair (“Rule 3. Eschew deviousness”), his real-time tallies of conquest and failure, and how his logic warps and loops as the days become “seasoned” by Charlotte’s “imminent presence.” In the scene when Harold meets Charlotte’s doctor-in-training husband and immediately clocks him as a moron governed by the boring principles of “cause and effect (in that order),” we see how unaware Harold is that he’s driven by precisely this rhythm, winning Charlotte with the arithmetic of affection, then retreat (in that order). Success is a zero-sum procedure, Harold thinks, and as he makes his new lover cry, tells her she’s being insane, loathes her privately, and commits casual infidelities, consensual reality falls into an all-swallowing, Harold-shaped void. Charlotte’s pain is his kindling. “I could break her like an ear of corn if I wanted,” he affirms at one point.

Stories about cruel, corrosive men tend to veer noirish, gratuitous, or at the very worst, didactic. Bean’s intervention is that his excellent bedside manner—crisply authoritative, gentle to his subject, grisly, but only out of necessity—offers no delusions that Harold’s way of life could possibly be worth it. Bean’s case study is a serious scrutiny into how his specimen of perpetual crisis lives with what he’s done: as Harold promised, Charlotte is met with ruin, meeting a disgusting end as hurt and infected as he is. The novel’s finale is as conclusive as a proof. “I hurt,” Harold notes, ergo, “and wanted to hurt her.” When Charlotte fantastically dies, Harold is surprised to learn that he loses something of himself, and “would not mind losing some more.”

I reacted to the end of The Nenoquich as I did to an understatement from the middle of The Believer. “With you,” goes the skinhead’s fascist girlfriend, “there’s a tragic dimension.” The Nenoquich’s final dimension is certainly tragic, but not just because of the dizzy downward slope angling Harold’s universe. It’s in the dimension’s perpetuity, deadlocked in a creature so wanting for meaning, impatient for plot, atrociously creative. “What does it mean to be an asshole?” Harold wonders in the middle of a manic passage. “It means you can’t stop.”

Mina Tavakoli is a writer from Virginia.